The First Fleet and the Anglican Church

Reflections

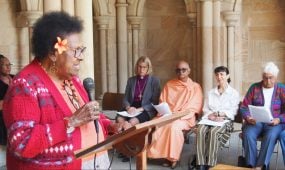

A reflection on the 231st Anniversary of the first Anglican service at what is now known as Sydney Cove and the First Fleet Chaplain The Rev’d Richard Johnson

On Sunday 3 February, we will commemorate the 231st Anniversary of the first Anglican service at what is now known as Sydney Cove.

The First Fleet reached the country of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, at what is now known as Port Jackson, on Saturday 26 January 1788. It was not possible to hold a service the following day, which was a Sunday.

On the following Sunday, the Governor Arthur Phillip, with about 1500 people, including civil servants, soldiers, marines and convicts, assembled on a ridge above what is now known as Sydney Cove for Divine Service. The service was conducted by the Chaplain, The Rev’d Richard Johnson, and it consisted of Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, a sermon and Ante-communion.

The scripture text for the sermon was Psalm 116: 11-12: “How shall I repay the Lord for all his benefits to me? I will take up the cup of salvation and call upon the name of the Lord.” We do not know what Johnson said, but following the conventions of the late eighteenth century, he probably spoke for about forty-five minutes.

Standing in the summer sun, many people in the congregation would likely have been bored, restless and morose. Most convicts had been disaffected from the Church before the commencement of penal servitude, and Irish Roman Catholic prisoners would have resented forced attendance at services of the Church of England. Attitudes among non-convict members of the congregation would not have been any better, and it seems that the majority felt that they had no need to thank God for the voyage into the unknown and away from family, friends and familiar places. But, there may have been some who wanted to express gratitude for a safe voyage to a strange and distant land.

Richard Johnson was a product of the eighteenth century evangelical revival in the Church of England. He accepted the chaplaincy of a ‘penal colony’ because he had a great concern for the welfare of underprivileged people. The early evangelicals were people motivated by a strong sense of responsibility to the outcast, and Richard Johnson was a friend of both William Wilberforce, Member of Parliament for Kingston-on-Hull and advocate for the abolition of the slave trade, and John Newton, a former slave trader and author of the hymn Amazing Grace.

Advertisement

Johnson was sorely tested as Chaplain, and even though he displayed great kindness and tenacity, his ministry was characterised by frustration and apparent failure. The Governor regarded the chief duty of a priest to be the enforcement of Christian moral principles. It seems that he was not interested in the issues that concerned Johnson: the conversion of sinners, the teaching of Anglican doctrine and the offering of prayer. The relationship with the authorities deteriorated under Phillip’s temporary successor, Lieutenant-Governor Francis Grose. Grose commented that Johnson was “one of those people called Methodists, a very troublesome, discontented character”. He was even less favourably disposed to notions of personal holiness than Phillip.

At his own expense of 67 pounds, Johnson built a church, Saint Phillip (spelt with two ‘l’ letters in honour of the Governor) on a ridge to the west of what is now known as Tank Stream. The simple ‘wattle and daub’ structure was burnt down in 1798, presumably by those who disliked compulsory church attendance. Johnson was reportedly friendly toward the local Gadigal people, and he gave his daughter, born in 1790, the Aboriginal name ‘Milbah’. He was a farmer, and the survival of the people from the First Fleet depended on his ability to propagate crops. Johnson returned to England in 1800 as a disappointed and broken man. He died in 1827 at the age of 71 years.

Advertisement

I think that many of us can identify with Richard Johnson, and for both clergy and laity there are times of sadness mingled with joy. Johnson may not have ‘reaped’ harvests of conversion, but he certainly ‘sowed’ seeds of faith. The Anglican Church of Australia has a strong tradition of social care, and ministry among people who are frail aged, sick, poor, homeless, imprisoned and service men and women, and this flows from a tradition established by Johnson.

The Church exists for people who do not attend, and a fundamental Gospel principle is that we care for people who live on the margins of society. We all like to know if we are successful in ministry, but we do not know. I suspect that if we did know of our success that we would believe that ministry depended on our own abilities, and not on the grace of God. The measure of ministry is our faithfulness to our Lord Jesus Christ.

The Anglican Church Southern Queensland “recognises the injustices that have led to disadvantage among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” since the First Fleet “and seeks to develop opportunities for Indigenous people to flourish”, continuing to work toward Reconciliation (Reconciliation Action Plan, p.15).