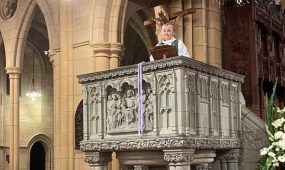

Archbishop's sermon: 10th Anniversary of Cathedral Consecration and Feast Day of St Simon and St Jude

Homilies & Addresses

“Being prepared to listen and to learn from others who are different, presupposes that no one person or group can possess the whole truth of the infinity of God,” says Archbishop Phillip Aspinall

Today the Church celebrates the festival of Saints Simon and Jude, apostles and martyrs.

Little is known about these two saints. The Simon we remember today is Simon the Less, not to be confused with Simon Peter, on whom Jesus said he would build his Church. Luke’s Gospel tells us that he was a zealot at one stage. And we think Jude was the one who was also called Thaddeus in the New Testament.

Tradition has it that Jude went with Simon to preach the gospel in Persia where they were martyred. Jude is often symbolised by a club because he was beaten to death. But he’s also represented by a boat because he may well have been a fisherman like the sons of Zebedee, James and John, who were his cousins.

Jude is best known these days as the patron saint of hopeless causes. That’s probably due to the fact that Jude was hardly ever invoked by anyone because his name was so close to Judas Iscariot who betrayed Jesus.

Jude wrote a short letter which made its way into the New Testament canon. It’s a single chapter of only 24 verses, but important, despite its brevity.

Jude wrote to the church because he was concerned that the church was in danger of losing the truth and being misled by intruders who ‘pervert the grace of God’ and ‘deny … Jesus Christ’ (v.4). In words which are often repeated today, Jude urges his readers ‘to contend for the faith that was once entrusted to the saints’ (v.3).

Advertisement

This is Jude’s first concern: that the church will safeguard the truth and not be led into error.

But he also has a second concern. Towards the end of his short letter he warns of ‘worldly people, devoid of the Spirit, who are causing divisions’ in the church (v19). So he urges believers to ‘build yourselves up on your most holy faith: pray in the Holy Spirit; keep yourselves in the love of God; look forward to the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ that leads to eternal life’ (v. 20). Jude is concerned, secondly, that divisions don’t fragment the unity of the church.

So on the one hand, truth must be safeguarded and, on the other, unity must be preserved. Truth and unity, – both, – together.

Now you don’t have to look too far today to see that questions of truth and unity are still big issues for both the church and our wider society.

How can we know what is true, in the face of competing and contradictory claims? How can we even examine competing claims in a careful and reasoned way when interactions these days take place through shouting at each other on social media.

Advertisement

Culture and technology seem to have colluded to polarise us to such an extent that truth seems to have been reduced to who can shout loudest; and the possibility of living together reasonably, peacefully, graciously, seems a lost pipe-dream. Increasing conflict, fragmentation and disintegration seem to many to be inevitable, in both church and broader political contexts.

In these unhappy circumstances, what does our faith have to offer?

Well I think Anglicanism, in particular, has something counter-cultural to offer.

Anglicans have lived with the tensions between truth and unity for a very long time.

It is the unique character of Anglicanism that it tries to hold together in one church a number of strands that are in tension with each other.

There’s what might be called the catholic strand that emphasises the traditional faith and order of the universal church. This strand insists on the value of our heritage and the place of ecclesiastical authority stretching right back through history, through the apostles to its original source in Jesus Christ himself.

Secondly, there’s what can be called the protestant strand. It affirms the reformation emphasis on the immediate, direct relationship between an individual believer and God through Christ. It emphasises the authority of the scriptures.

And thirdly, Anglicans tend also to emphasise the importance of the search for truth, of intellectual freedom and inquiry. There’s an openness to what’s being discovered by reason and research and artistic enterprise in all the other disciplines and endeavours pursued in the community at large.

Now at times Anglicans have been criticised. We’ve been accused of a kind of ‘anything goes’ approach. Because we embrace catholic, evangelical and reasoned dimensions of faith sometimes it’s said that you can believe anything you like and still be an Anglican!

What’s really being said when this accusation is levelled against us, is that Anglicans have given up on the search for truth. We’ve chosen to be so inclusive, so comprehensive, giving everyone and every perspective a place, that we’ve made unity and inclusion a higher priority than standing up for what is true.

But I think that is to misunderstand Anglicanism. And anyone who has to deal with the reality of church politics and decision-making in the Anglican Church soon learns that Anglicanism is not a recipe for cheap and easy institutional peace and harmony at the cost of truth. Quite the opposite is the case.

At the heart of Anglicanism are dynamic tensions among these three sources: scripture, tradition and reason. We tend to say that no single emphasis or group in the church is the sole possessor of the whole truth. Each perspective grasps part of the truth and it has to be heard. But the whole truth will only be comprehended as each of these sources reveals its truth in dynamic interplay with the others. Sometimes the three perspectives will readily agree and confirm each other. At other times they will appear to say different things and be in tension with each other.

So there’s a heartbeat of constant tensions going on in the core of our church.

And Anglicans often end up somewhere in the middle of two extremes in important debates. There is what’s called the via media, the middle way. But it’s a mistake to think that the Anglican via media is an easy compromise for the sake of peace and harmony and at the expense of hard-won truth.

That’s not what’s going on at all. The various perspectives constantly challenge and correct the others. So at the heart of our church is a kind of dialogue that needs a great deal of effort and energy to sustain. We work hard at staying together, at unity, even when we disagree, because we know that we need each other in order to comprehend the fullness of the truth.

This inner dynamic, that’s at the heart of the life of our church, is a real gift that we can offer to the wider community in polarised, fragmented times.

If the different religions and cultures and political ideologies in our world are going to find a way to live beside each other in peace and harmony and continue with their search for truth, we will need to cultivate the kinds of attitudes that Anglicans work hard at.

We will have to be prepared to listen to each other, to understand each other and to learn from each other. The alternative is the kind of ignorance of other faiths and cultures, the mistrust and suspicion that produce fear and prejudice and hostile non-communication.

Being prepared to listen and to learn from others who are different, presupposes that no one person or group can possess the whole truth of the infinity of God. That should be self-evident: finite human minds cannot grasp the infinity of God.

That’s not to say that we give up on the search for truth. Far from it. But we need to join the search with a certain attitude of humility. Confident to share our own deeply held convictions, but also recognising there are elements which we are yet to see, and which might be shown to us if we listen to others.

In our world today truth and unity are often played off against each other. Some extremists claim to be the sole possessors of the truth and would cut off all who disagree. They are convinced they have the whole truth and are prepared to sacrifice unity for it. That’s a recipe for fragmentation and conflict.

Others give up on the search for truth altogether and say you choose your truth and I’ll choose mine. But that easy peace is no peace and in the end will lead to disintegration.

We must hold both truth and unity together as St Jude urges us. Tonight, we also mark the tenth anniversary of the consecration of this Cathedral. To my mind it stands as a breathtakingly beautiful monument to the dynamics of human life I’ve been describing. This Cathedral speaks eloquently of the infinity of God and encourages the humility of heart and mind that are required to see God.

This Cathedral is home to vibrant communities of diverse people willing to explore together and learn from each other and to draw close to each other and to Christ. This Cathedral values the best in scholarship, in prayer, liturgy and mysticism, in the arts – music, theatre, sculpture, poetry, writing. We value all this because we appreciate that God speaks to us in all these ways and binds us together in Christ in the Spirit.

Our hearts are filled with gratitude tonight for the work of so many since 1901 whose labour and generosity created this gift for others. To builders, benefactors, fundraisers, visionaries, leaders and faithful servants of God, for thousands and thousands of the saints of God who contributed to making this bold statement, we join together tonight to bless the Lord.

This Cathedral stands for truth and unity as St Jude urged. May God bless its every endeavour and make it a faithful vehicle of that reconciliation of all things in Christ, which is God’s will and gift. Amen.

This sermon was given by Archbishop Phillip Aspinall during Evensong on the 10th Anniversary of the Consecration of St John’s Cathedral and the Feast Day of St Simon and St Jude on Sunday 27 October.