The Parable of the Wicked Tenants sermon

Homilies & Addresses

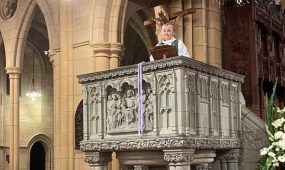

“Our God is a God of surprises, always waiting in love for us, always waiting to give more of God’s self to us and hold our hands to grow into the people that we have been created to become. Jesus is the cornerstone and pattern maker of our faith, encouraging us to move forward with love, humility and searching,” says Kate Littmann-Kelly from St Andrew’s, Indooroopilly

Through our lectionary readings for Sunday this year, we have been working our way through the Gospel of Matthew and we have been listening for many weeks to parables.

If we were to ask each other about our favourite parable, I wonder which one it might be?

One of the expansive, generous ones about the outrageous love of God maybe — The Parable of the Lost Sheep or maybe The Prodigal Son? Maybe one to make us think about our relationships — The Good Samaritan might be popular…

But I suspect that the Gospel reading from today, The Parable of the Wicked Tenants, might not rate particularly highly in the list of best loved parables.

Tenant farmers are entrusted with the care of a vineyard for an absentee landowner; they beat, stone and finally kill the emissaries who come to collect the landowners share of the yield. As a last resort, the landowner sends his son, but the tenants have no respect for him and kill him, hoping to keep the land for themselves. In an escalating cycle of violence, it’s anticipated that the landowner should send the tenants to a miserable death.

This parable is the second of three parables in Matthew that Jesus directs against the Jewish leaders. Jesus is set up in the temple and debating the chief priests and the Pharisees, and the conflict between them has reached a boiling point. You can almost sense a tone of frustration at the beginning of the reading today: “Listen to another parable”.

The Pharisees clearly don’t think that Jesus has divine authority to speak to them, and their minds have remained unchanged by the witness of John the Baptist. The stage is set, and this is one of the last parables we’ll hear before Christ’s passion.

Advertisement

We can read this parable as an allegory. The landowner is God the Father; the tenant farmers are the temple authorities responsible for keeping the synagogue traditions and teachings; the son is Jesus; and, the servants who go before the son and get beaten up are the law and the prophets. The vineyard is the world; the fruits are works pleasing to God; and, the new tenants are the new Christian church, with Christ as the cornerstone of it all. Those who reject the cornerstone will be crushed and “broken into pieces”.

If we read it this way, then it’s not just a prophetic critique of the religious leadership of Israel, but a seismic shift in salvation history.

In this reading, God has run out of patience with the covenant people Israel and the title of God’s chosen people has shifted from the Jews to the newly minted Christian church. The kingdom of God is taken away from the Jews and given to a people that produce the fruits of the kingdom. In this reading, Israel’s rejection of Jesus will result in disaster, condemnation and judgement. This reading (and reading the New Testament as a whole with this lens) has led some to rejoice that Christ is the keystone of our faith, but has also resulted in anti-Semitic sentiment and a spirit of triumphalism, rather than producing fruits of repentance, mercy, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Allegory is notoriously difficult to control.

Advertisement

More challenging still is that the allegorical parables that stretch from Matthew 18-25, frequently cast God in a violent and unmerciful light — a king angrily settling accounts, an unpredictable employer, a landlord inclined to violent revenge, a condemning bridegroom and the host of a wedding banquet with anger management issues. These parables are a far cry from the words of Matthew 5.44-45, “But I say to you, love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

So those are some of the problems. What do we make of this parable?

When reading the Gospel of Matthew, we always need to remember that the writing community probably has an edgy relationship with Judaism. It’s been written shortly after the fall of Jerusalem; there is no longer any temple synagogue — this spiritual centre of the Jewish faith has been destroyed by the Roman Empire and the Jerusalem population has fled and scattered. One thought is that the Matthean community now lived in the same geographic region as the Jewish Pharisees and both groups are now trying to grasp the higher spiritual ground and make a claim for who is the true Israel and represented authentic Torah interpretation. Matthew’s is the least outward looking of the Gospels and goes to great pains to define his community — to create boundaries between those who are “in” and those who are “out”.

While this throws an interesting light on the history and times of the early Christian church, and some of the unhelpful ways that the more modern church has understood this parable, we would do well to allow this parable to speak to us today, otherwise we have missed something valuable. Because we are the present caretakers and workers in God’s vineyard, we hold the Church’s faith and theological traditions; we are producing fruit in the world.

I think this parable offers us a couple of lovely opportunities to ponder:

- The parable invites us to consider what it means to be stewards of the vineyard. The parable affirms Jesus’ awareness that his fate is in the hands of the Jewish authorities. Like other parables that include Jesus’ response to the temple authorities, this story focuses on the nature of power. The leaders power lies not in mercy, but in their control over land and temple. They have sought to claim for their own what they were given as stewards. With these images, Matthew paints a picture of illegitimate power exercised outside of God’s mercy. Every day the Church faces questions about how it will respond to such power in the world. And we should question ourselves about our own exercise of power.

- This parable invites us to ponder about the way we reject God when we define some people as “the other”, and make judgements about who is “in” and who is “out”. When traditional readings of this parable have invited “othering”, how do we move past that into a space of acceptance and grace? The building of boundaries and deciding who is and who is not included in the kingdom, is not our call to make: it is exclusively God’s business. We can’t ignore injustice in society, violence in the world or wrong in our Church, but we are called to respond in trust, obedience, patience and care to the calling that God has entrusted into our hands right here.

- This parable offers us the opportunity to reflect on what we do when confronted with a contrary witness to the truth we accept and believe in. The temple authorities knew their religious faith and were zealous guardians of their traditions — but there in the synagogue, while they verbally sparred with Jesus, they did not accept that Jesus had authority, and they did not accept the prophetic witness of John the Baptist. But are we the same, holding tightly to the firm knowledge of how God will work?

Of course we must be discerning, but are we open to the workings of the Holy Spirit and the surprising twists and turns that the living God can bring? What if that word unsettles us or threatens our authority? Looking back we can acknowledge with shame the Church’s response to prophetic voices regarding racial injustice or the role of women or definitions of the family. Put in its best light, we attempt to safeguard the Gospel from unrighteousness or unsound doctrine. But in another light, we can be blind to the light of God shining in unauthorised or unexpected sources and voices, especially when that light shines on our own error and misunderstandings of scripture.

Our God is a God of surprises, always waiting in love for us, always waiting to give more of God’s self to us and hold our hands to grow into the people that we have been created to become. Jesus is the cornerstone and pattern maker of our faith, encouraging us to move forward with love, humility and searching. To paraphrase the writing of William Paul Young, the redeeming genius moves inside our mixed motives and intentions, both the darkness and the light, and blesses with life anything that is still of love’s kind, and now continues to work within the ripples to redeem everything. Sometimes, it is only in retrospect that we can see any of this is amazing in our eyes.

Amen

Editor’s note: This sermon was given at St Andrew’s, Indooroopilly by formation student Kate Littmann-Kelly on Sunday 8 October 2023.