Ascension Day

Features

“In ascending into heaven, Jesus completes creation, and through him all things are returning to him from whom they have taken their origin,” says The Ven. Keith Dean-Jones OGS on Ascension Day, which is marked in our Lectionary on 21 May

Thinking about the Ascension of Jesus into heaven can present us with difficulties. It may imply a crude cosmology, and the teachings of 17th century English ‘Muggletonians’, that heaven is six miles above the earth and that 40 days after his resurrection from the dead, Jesus stepped onto a cloud that elevated him to his final destination, are naive.

The more serious problem is that the Ascension may suggest Jesus’ absence. But Jesus is not “that dreaming, dark, dumb Thing; That turns the handle of this idle show”, the cynical remark of the English 19th century poet and novelist Thomas Hardy in the poem ‘The Oxen’. He is the one who is with us to the close of the age (Matthew 28.20), the one whom we desire and experience as Emmanuel, God with us. Throughout history, men and women have recognised the presence of the Good Shepherd who ‘lays down his life for the sheep’ (John 10.11) as he leads his flock to the heavenly Jerusalem (Psalm 23), the place of life, love and joy.

Advertisement

The Ascension points to the purpose of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. Peter affirmed that God’s gift is that we will be partakers of the divine nature (2 Peter 1.4), and Paul boasted in the hope of sharing the glory of God (Romans 5.2). The Greek Fathers used the word ‘divinisation’, and Egyptian theologian Athanasius of Alexandria (c.296-373) asserted that “Jesus Christ was made human so that he might make us gods” (De Incarnatione 54.3). In ascending into heaven, Jesus completes creation, and through him all things are returning to him from whom they have taken their origin.

In Jesus humanity is united to God. For western Christians, this language may seem unusual. It does not mean that the division between the Creator and creatures is breached; God is still God and humans are still humans. Rather, divinisation affirms that, by God’s grace, we are being transformed into the likeness of him who is both God and human, our Lord Jesus Christ. As Paul writes:

“And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit” (2 Corinthians 3.18).

Related Story

Reflections

Reflections

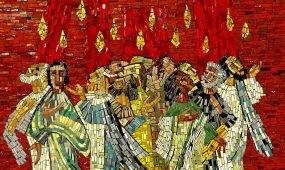

Pentecost: fulfilment of ancient prophecy and a new awakening

I think that our divinisation is also our humanisation. We live in a culture that exults in youthfulness, and it seems that people are regarded as being ‘over the hill’ when they have reached 40 years of age. Old age is rarely regarded as a good experience. But I think that it is good to grow old and that, by God’s grace and our willingness to respond to his love by dying to selfishness, we can become more and more the person that God has created us to be. Like an old pair of slippers, we may appear a bit shabby, but the slippers are comfortable – for the inner person has been and will continue to be transformed.

God’s creation is dynamic, not static. We are born human and we are becoming human. Jesus’ humanity is a template for what it means to be a man or a woman, and his capacity to love, forgive, understand, reconcile and act with justice reveals that he is “the way, the truth and the life” (John 14.6). Many of the congregations that constitute the Anglican Church Southern Queensland consist of mature-aged people. This is good and it reminds us about Jesus’ claim when he said, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10.10).