The ‘immortal’ woman: Henrietta Lacks

Features

“This is a story about some of the world’s most important cells. Their code name is ‘HeLa’ and for several decades now they have been bought, sold, packaged and shipped by the trillions to laboratories around the world. It is a fascinating story and it would be an injustice not to tell the tale of Henrietta Lacks – the woman who ‘owned’ the groundbreaking HeLa cells,” says The Rev’d Dr Imelda O’Loughlin

Recent discussions about COVID-19 vaccine development have brought the names ‘Henrietta Lacks’ and ‘HeLa cells’, named using the first two letters in ‘Henrietta’ and ‘Lacks’, back into media conversations.

This is a story about some of the world’s most important cells. Their code name is ‘HeLa’ and for several decades now, they have been bought, sold, packaged and shipped by the trillions to laboratories around the world. It is a fascinating story and it would be an injustice not to tell the tale of Henrietta Lacks – the woman who ‘owned’ the groundbreaking HeLa cells.

Henrietta was born in Virginia in 1920. She was just four years old when her mother died in childbirth leaving Henrietta and her nine siblings in the care of their dad. Soon after, Henrietta went to live with her maternal grandfather. Grandpa Tommy worked a tobacco farm and from dawn to dusk his fields overflowed with Henrietta’s cousins. While the children worked hard, they still found time to run and shout, dam the creek to create a swimming hole, swap secrets, and build close friendships. They often ended their busy days telling stories and gazing up at the stars until Grandpa Tommy sent them all scattering to bed.

At age 20, Henrietta married one of her cousins. Day was five years older and the young couple already had two children. Henrietta and Day struggled to provide for their family and, despite the flourishing of the large tobacco holdings, they were lucky if they sold enough tobacco from their small plot to feed their family and plant for the next season. In late 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbour, and the United States subsequently declared war, with the demand for steel in the United States then booming. Henrietta and Day left their land and followed many of their friends and family in a movement that became known as ‘The Great Migration’. African American families from the South, moved to the cities of the north, Midwest and west to find work on the burgeoning industrial sites. Henrietta and Day settled their family in Sparrows Point in Maryland and Day worked in what was at that time the largest steel plant in the world.

Advertisement

Henrietta is remembered for her warm hospitality. She would regularly take in newcomers to the steelworks and house them until they were settled. She would ride with them on public transport so they didn’t get lost on the way to work and she often packed extra food to take to the worksite for any who were hungry. It seemed that everyone loved Henrietta.

Just 10 years after her marriage, Henrietta confided to a few of her very close friends that she had a “knot” inside her. She waited until she and her friends were at the very top of a Ferris wheel before breaking the news, knowing that there she could not run away from the facts and neither could they. Henrietta had cervical carcinoma. Despite treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital, which was one of the few institutions in America at the time to treat African Americans, the malignancy quickly claimed her life.

Henrietta died in 1951, but cells taken from a cervical tissue sample without her consent for research purposes, are still multiplying more than 70 years later. For several years, researchers at Johns Hopkins Hospital had been collecting cells from the tissue samples of patients with cervical cancer for research purposes, but each sample quickly died. Henrietta’s cells were different as they multiplied rapidly, doubling every 20 to 24 hours. Henrietta’s cancer cells became the first immortal cell line and still we do not know why they have never died.

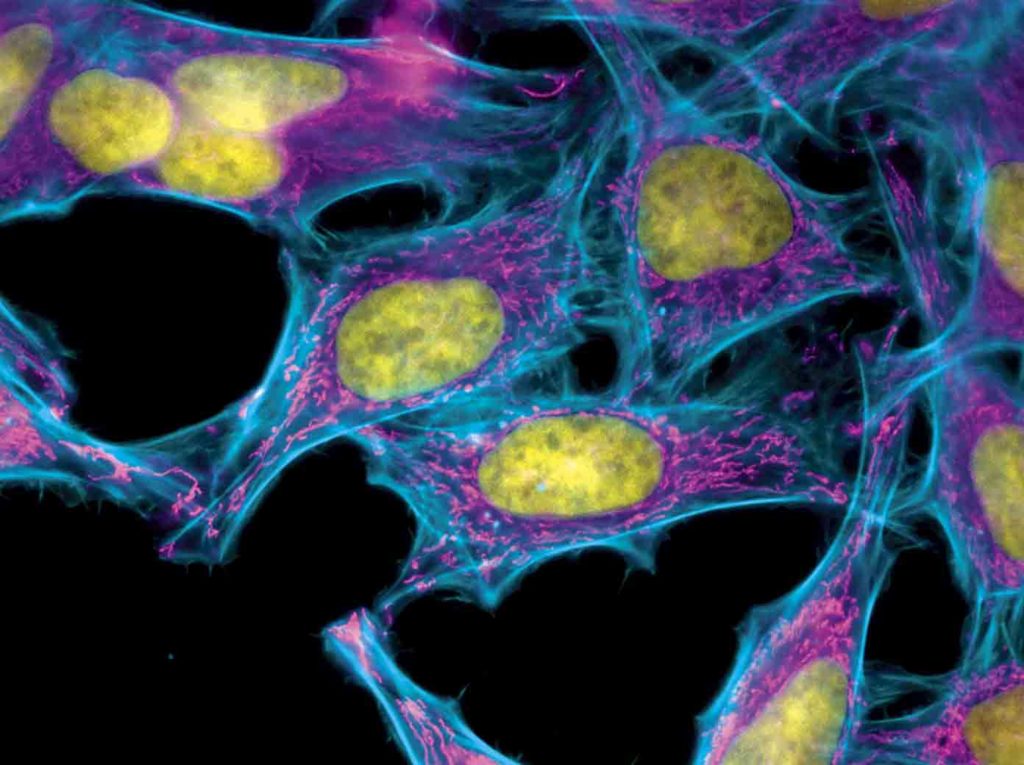

HeLa cells (image used with permission, courtesy of Omar Quintero)

Her cells helped to develop drugs for treating herpes, leukaemia, influenza, haemophilia and Parkinson’s Disease. They’ve been used to study lactose intolerance, sexually transmitted diseases, appendicitis, human longevity, mosquito mating and the negative cellular effects of working in sewers. Henrietta’s cancer cells have also helped with some of medicine’s most important advances including a polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping and in vitro fertilisation.

One of Henrietta’s cousin described her as someone who “made life come alive – bein with her was like bein with fun…She was a person that could really make the good things come out of you.”

Advertisement

Sadly, Henrietta couldn’t bring out any good in the wife, Ethel, of another cousin. After Hennie’s death, Ethel and her husband moved in with Day. She starved and physically beat the children and, when they could, the children left home.

Henrietta’s surviving children Lawrence, Sonny, Deborah and baby Joe were never told what happened to their mum. She went to hospital many times and one day she simply didn’t come back. No one spoke to them of her death. Imagine then, finding out that your mother’s cells are alive and multiplying 25 years after her death! The news was bittersweet, alarming, and confusing.

Initially no one in Henrietta’s immediate family was particularly upset except Deborah who obsessed with the idea that part of her mother was still alive. Lawrence, Sonny, Joe and Day were busy patching their lives together, and were quite philosophical about it all. Sonny summed it up: “Long as it’s helpin someone.” It was not until 1975, when the brothers learned that biotech companies and cell banks were profiting from sales of the HeLa cells, that Lawrence and Sonny tried unsuccessfully to have the family compensated.

Understandably Lawrence and Sonny were angry that people had made money from their mother’s cells while her children starved. Joe was angry with life in general. He was only two years of age when Henrietta died and never knew her comforting love. All he could remember was being hungry, locks on the refrigerator and daily beatings at Ethel’s hands. With little formal education, Deborah tried to understand what it all meant. How could part of her mum still be alive? Did her mother’s cells suffer pain when they were split up, or exposed to radiation? Did the cells experience fear when they were taken up into space to study the effects of negative gravity on human cells? She sensed that all the experiments were a violent assault on her mother. If her mother’s cells were alive so long after her death, did that mean her children would live forever?

The story of Henrietta Lacks and her ‘immortal cells’ is a complex one of pain and sorrow, racism and poverty, violation of the right to privacy and consent, profit and medical advances. It is story about the beauty and drama of scientific discovery and of the often-forgotten tragic human consequences. As intriguing as the story of Henrietta’s cells is, it is important to remember those lives that were relinquished to the background – lives that were ignored, assigned no value, overlooked, and at times disguised and hidden.

I hope that in writing this, I have conveyed my deep personal respect for Henrietta’s life and her contribution to ours.

If you are interested in finding out more about Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cells, Rebecca Skloot has written an award-winning book on Henrietta’s story:

Rebecca Skloot, 2010. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Crown Publishers, New York.