Who’s In? Who’s Out?

Features

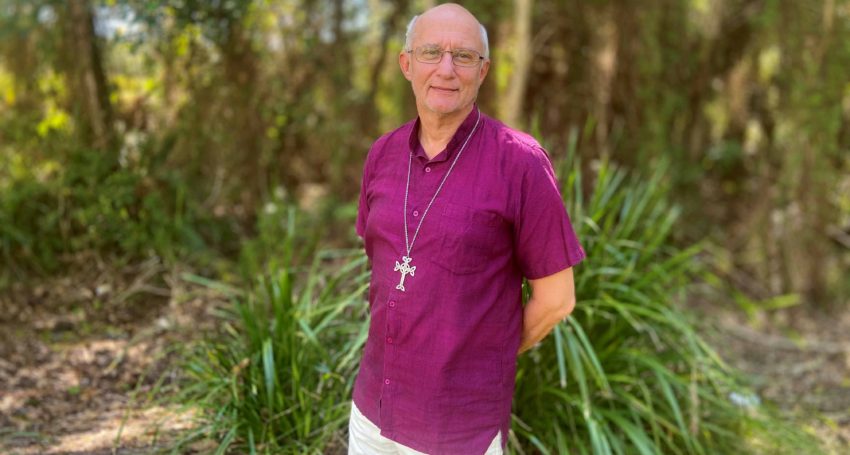

“To cherish and strive for a Church that welcomes all shades of faith and keeps the sacramental table open for all – the proud, the foolish, the misguided and the over-zealous – takes courage, tenacity and perseverance. In a fractious and divided world; in a time of great uncertainty beset by a pandemic and ‘alternative facts’, the Church of God needs to return to the Jesus of the Gospels,” says The Right Rev’d Professor Stephen Pickard

The alternative title for this short piece could be: ‘Let’s get real about being comprehensive!’ The trouble is the word ‘comprehensive’ doesn’t seem to cut it anymore. But, what it is really about certainly does. How so? Perhaps the best way to explain is to take a step back in time to Post-Reformation England.

In the early 17th century the first great ecumenical theologian of the Church of England, Richard Field, wrote a three-volume treatise (as one does) with the title: Of The Church. Not the most exciting of titles and would be difficult to market today, I’m sure. Field was a colleague of Richard Hooker, the architect of what might be described as Classical Anglicanism.

Field was a deeply learned scholar of a more Calvinist flavour. He was acutely aware of the divisions of Post-Reformation Europe. On English soil, he was concerned about the division between a broad-church Tudor Christianity, espoused by the likes of Hooker, and a resurgent Puritanism. Beyond this internal tension within the English Church, Field recognised the reality of Roman Catholic influence and was aware of the other great traditions of Eastern Christianity. The bitterness and pain of the 16th century reform had left scars and there remained deep unhappiness among the Puritans (or ‘Precisions’ as they were also known) that the Reformation had not gone far enough. In particular, they wanted to replace episcopacy with a Presbyterian form of governance.

So, who’s in and who’s out? Words like ‘inclusive’ and ‘comprehensive’ were not then part of the stock in trade language. Field argued that it was premature to pronounce judgement on who was to be included and who was to be jettisoned in the Church of God. For Field it was not a matter of being in or out of the Church of Jesus Christ. In this sense he was following Richard Hooker who argued, for example, that the Roman Church remained part of the visible Church of God, albeit with serious errors that nonetheless did not overturn the foundation of faith. Field agreed. Indeed, he went further, and this gave his work a truly ecumenical edge in a time of rancour and ill will amongst Christians.

Advertisement

Field argued that it was not a question of being in or out, but rather being of the Church. The prepositions were critical. To be of the Church was a more open and humble way of regarding Christians who differed over significant issues of scripture, doctrine, morals and ethics. The visible Church of God was constituted by a variety of different and divided Churches. It included schismatics and even heretics, although Field gave pre-eminence to those of a ‘right believing’ Church. He took a harder line on this than Hooker who spoke of a ‘sound’ Church according to the Rule of Faith (for example, regarding the Apostles’ Creed). However, more importantly, Field was unwilling, for theological and moral reasons, to prematurely unchurch other Christians. He developed what in time became known as the via media of the Anglican Church. In doing so, Field rejected the narrower ecclesial boundaries of Rome and radical Protestantism.

Field’s approach to the Church may not seem particularly earth shattering to us 400 years on. However, at the time his focus on being of the Church not only offered a far more inclusive, generous approach, it also retained a genuine openness to the future Church. It was simply not possible to say finally who was in or out, either in the present or in the time to come. At this point Field was following in the footsteps of the early Church theologian, Augustine of Hippo.

Advertisement

Field’s vision offered a reality check. Church division was real, and Christians had to learn to live with one another for the sake of witnessing the Gospel. His approach set the gold standard for the shape and character of the Church of England for its future. I say ‘gold standard’ because most certainly subsequent history shows how fragile his vision was and how difficult it was to resist the temptation to close the doors to those who were deemed not acceptable. It is a messy and sad story and, alas, remains so in some parts of the Church. Though from time to time there are those who have kept the flame of an open and generous Church alive. We desperately need more of them today!

To cherish and strive for a Church that welcomes all shades of faith and keeps the sacramental table open for all – the proud, the foolish, the misguided and the over-zealous – takes courage, tenacity and perseverance. In a fractious and divided world; in a time of great uncertainty beset by a pandemic and ‘alternative facts’, the Church of God needs to return to the Jesus of the Gospels.

They bear witness to a saviour who relentlessly kept the doors of the Kingdom open to so many, much to the chagrin and offence of the self-appointed good and righteous in his day. A comprehensive Church is a uniquely and inherently messy and challenging church. It is never the soft option; it is the road less travelled. This is the vocation and mission of those who travel the Anglican Way.