William Tyndale: the most dangerous man in Tudor England

Features

“Such was the anxiety about Tyndale’s translation that King Henry VIII bought 3,000 copies and had them burnt. However, this was to Tyndale’s advantage – for while the books were destroyed, he still received the proceeds of the sale! Having completed his translation of the New Testament, Tyndale began working on a translation of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew,” says The Rev’d Canon Dr Marian Free, as Tyndale is commemorated in our Lectionary on 6 October

As a student of the Bible, I am fascinated by the history of translation, in particular the translation of the Bible into English and the fact that such an endeavour was once considered heretical and punishable by death. In a world in which a variety of translations (and transliterations) are readily available, it is almost impossible to comprehend that for centuries the Bible itself was incomprehensible to anyone who was not proficient in Latin.

Reformer, translator and martyr William Tyndale (c.1494-1536) was utterly convinced that everyone, great and small, should have access to the scriptures, and though it was dangerous to do so, he was not afraid of speaking his mind. On one occasion he reportedly said: “I defy the Pope and all his laws. If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause the boy that drives the plough to know more of the scriptures than you!”

It is hard to say when I first encountered William Tyndale. I feel that as long as I have known that the Bible was not written in the language of King James’ England, I have known that the first translation into English was made by Tyndale. His work of translation forms the background of much Reformation history and was carried out at a time when an English translation was considered to be a threat both to the Church and state. In popular culture, you might remember a character in a recent movie or tele-movie in which a major character (possibly Thomas Cromwell) is depicted as pushing his copy of Tyndale out of view when representatives of the king come to visit. Having a Tyndale Bible in one’s own possession was punishable by the death sentence.

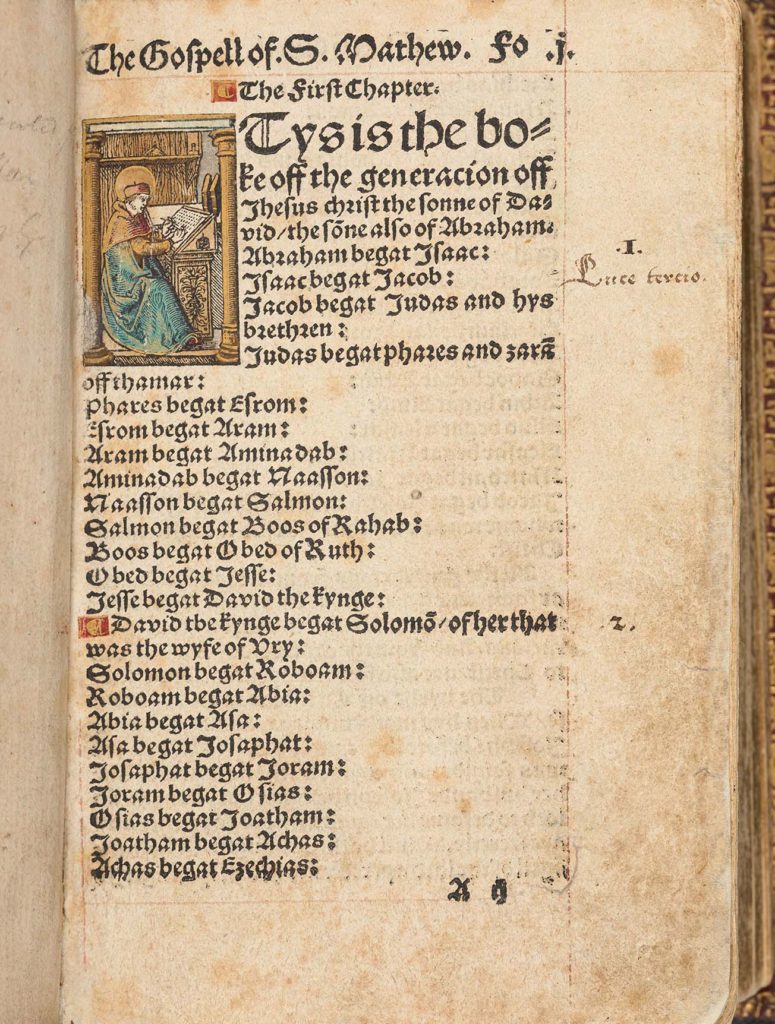

The British Library holds this original Tyndale New Testament

The years leading up to the Reformation were a time of intellectual foment and turmoil. Long held traditions and practices were being questioned, as was the authority of the Church. At the same time, a number of Greek intellectuals who had fled Constantinople when it fell to the Ottoman Empire, brought with them copies of the Greek Bible. For the first time in centuries, the Bible could be translated from its original language rather than from the later Latin versions. Tyndale read Erasmus’ Greek text and discovered, as had many reformers, the principle of justification by faith and came to believe that the theology of the Latin was seriously in error.

Advertisement

This put him into direct conflict with the Church, which emphasised the sinfulness of humanity and the need for confession (and purgatory) as a means to salvation. It was a theology that threatened the authority of the Church, which was why it was considered so dangerous.

By all accounts Tyndale had an extraordinary intellect and was extremely proficient at languages. By the time that he was 22 he was fluent in eight languages, including Greek. He was filled with a passion to make an English translation available to all his fellow citizens, so that everyone from the lowest to the highest could read the Bible for themselves.

To this end he applied to the Bishop of London for a grant. When the grant was refused Tyndale found backing in the form of a wealthy cloth merchant. He moved to Europe in 1524 in the hope of finding a more welcome environment in which to continue his work. He fled to modern-day Germany – first to Cologne and when he was discovered there he moved to Worms. In 1525 his first edition of an English translation was published. Copies were smuggled into England in bales of cotton where they could be bought for the equivalent of a week’s wages. The invention of the printing press ensured that numerous copies could be made at one time and at very little cost.

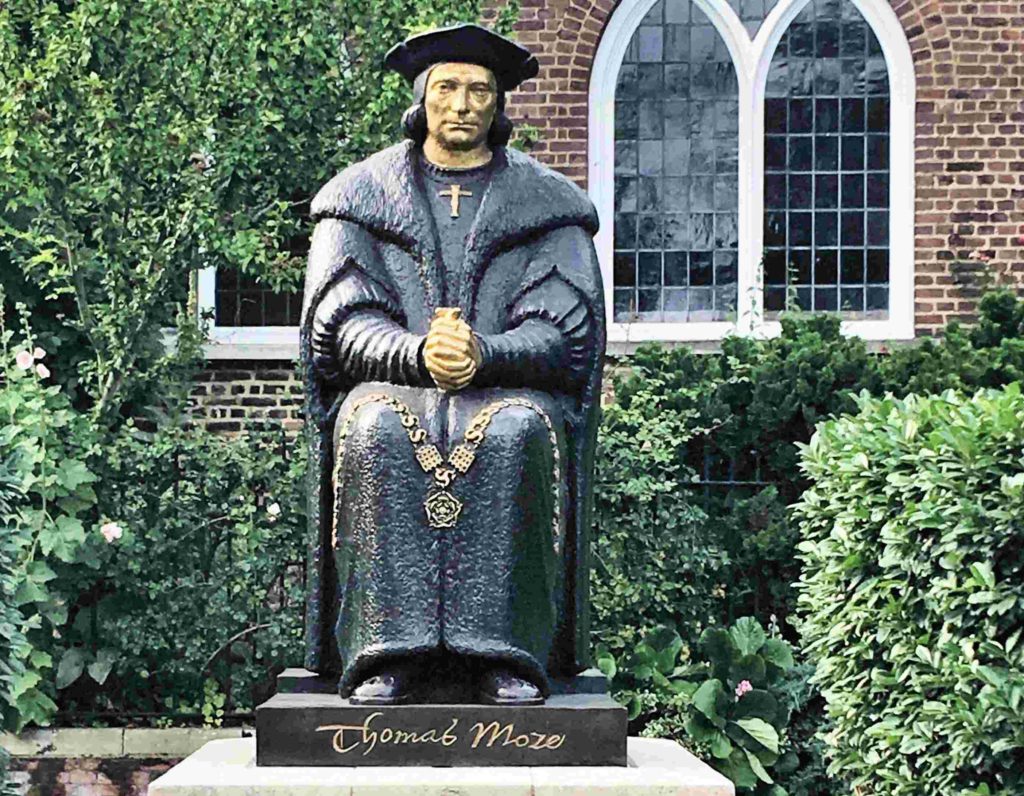

His translation caused such offence that lawyer Thomas More (1478-1535) said: “it is not worthy to be called Christ’s testament, but either Tyndale’s own testament or the testament of his master Antichrist.”

A statue of Sir Thomas More in Chelsea, London

Such was the anxiety about Tyndale’s translation that King Henry VIII bought 3,000 copies and had them burnt. However, this was to Tyndale’s advantage – for while the books were destroyed, he still received the proceeds of the sale! Having completed his translation of the New Testament, Tyndale began working on a translation of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew.

Tyndale’s translations were considered to be such a threat to Church and state that even in Europe he was not safe. He was sought by representatives of both the English King and the Pope. For a time, Tyndale managed to evade the authorities and occupied himself not only with the work of translating and writing, but with pastoral work among his fellow countrymen and women who had also fled religious persecution in England: “on Saturdays he walked Antwerp’s streets seeking to minister to the poor (Christianity Today).”

Advertisement

Eventually he was betrayed by one Henry Phillips who had managed to gain his trust. Phillips lured him into a trap. Tyndale was accused of heresy and imprisoned in the Castle of Vilvoorde. He was examined by representatives of the Holy Roman Empire and finally condemned, stripped of his office and “handed over to the secular authorities for punishment (Christianity Today).” On 6 October 1536 at the age of 42, he was strangled before the pyre on which he stood was torched. Apparently his last words were: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes!”

Within four years of his death, four English translations of the Bible were published in England, including Henry the Eighth’s Great Bible.

The Tyndale Monument is a tower built on a hill at North Nibley, Gloucestershire, England

Tyndale’s legacy continues today. Though only three copies of his original translation exist, so good was his translation that more than 80 per cent (some say 90 per cent) of the King James version is derived from Tyndale’s translation.

Furthermore, many phrases that we use today came from his pen, including “The spirit is willing”, “Eat, drink and be merry” and “Fight the good fight”. On occasions when there was no equivalent in English for the Greek word, Tyndale supplied one. Words that he invented include “scapegoat”, “atonement” and “Passover.”

In the face of death, Tyndale remained committed to his goal and all these centuries later we are the richer for it.

The plaque on the Tyndale Monument in Gloucestershire reads: ERECTED A.D. 1866 IN GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE OF WILLIAM TYNDALE TRANSLATOR OF THE ENGLISH BIBLE WHO FIRST CAUSED THE NEW TESTAMENT TO BE PRINTED IN THE MOTHER TONGUE OF HIS COUNTRYMEN BORN NEAR THIS SPOT HE SUFFERED MARTYRDOM AT VILVORDE IN FLANDERS ON OCT 6TH 1536

Just east of St James’ Park in London, off the bank of the River Thames in the Whitehall Gardens, is a large statue of William Tyndale, with a bronze plaque that reads: “William Tyndale First translator of the New Testament into English from the Greek. Born A.D. 1484, died a martyr at Vilvorde in Belgium, A.D. 1536.“Thy word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path” – “the entrance of thy words giveth light.” Psalm CXIX. 105.130. “And this is the record that God hath given to us eternal life, and this life is in his son.” I. John V.II. The last words of William Tyndale were “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes”. Within a year afterwards, a bible was placed in every parish church by the King’s command.”