“Initiating a new world for all of us”

Features

“As we honour the virtues of Queensland greats Robert and Grace Atkin and their devotion to ‘initiating a new world for all of us’, what lessons can we learn about stepping across the line to bridge difference?” asks Bishop Jeremy Greaves

I recently had the privilege of speaking at an event in Sandgate that commemorated Queensland’s Atkin family. The special event included the dedication of a restored Hibernian Society of Queensland monument to Robert Travers Atkin, with Chief Justice Susan Mary Kiefel AC also speaking.

In his co-authored book The Parables of Jesus, US-based theologian Professor Bernard Brandon Scott writes at length about the Parable of the Good Samaritan. He finishes his commentary on the parable like this:

“[The parable] proposes a new world in which the wall between ‘us’ and ‘them’ no longer exists and even more that one of ‘them’ can come to the aid of ‘us’.”

He goes on to write:

“There is another way to imagine this parable. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is the same story but with the ‘us/them’ still firmly in place. When Romeo and Juliet step across the line between the Capulets and the Montagues, no one else from either family follows. And so the tragedy plays out in its inevitable end in the deaths of the two young lovers.”

This comparison of Romeo and Juliet points out that Jesus’ parable and Shakespeare’s play are not about individuals, but about communities. It is not just individuals who have to cross the line – communities have to cross the line as well. Yet the crossing of the line always begins with the first Samaritan whose heart is moved by a Jew.

Scott finishes with: “Such people are initiating a new world for all of us.”

Advertisement

It is, therefore, appropriate to reflect on the Parable of the Good Samaritan while reflecting on the Atkin family and their contribution to the community.

Robert Travers Atkin was only 31 when he died 150 years ago in 1872. His life was tragically cut short by illness. His virtues and achievements set an example for others to follow, including his infant son, James Richard (Dick) Atkin, who drew on the “neighbour principle” as a judge in the foundation of modern negligence law.

In the language of the day, the monument’s broken column is described as symbolising:

“…the irreparable loss of a man who well represented some of the finest characteristics of the Celtic race – its rich humour and subtle wit, its fervid passion and genial warmth of heart.”

The inscription on the monument describes how Robert Atkin was distinguished in the press and in Parliament by:

“…large and elevated views, remarkable powers of organization, and unswerving advocacy of the popular cause, his rare abilities were especially devoted to the promotion of a patriotic union among his countrymen, irrespective of class or creed, combined with a loyal allegiance to the land of their adoption.”

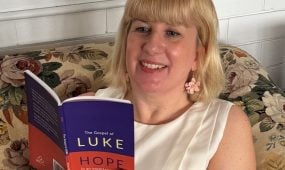

Robert Travers Atkin (1841-1872) (Image sourced from Wikimedia Commons: Public Domain)

Robert Atkin and his friends had a ground-breaking vision for Queensland’s future. They opposed vested interests and corruption. Robert was an advocate for fairness towards people in the north, for new railways, and for the new industries of cotton and sugar. He described the Polynesian Labourers Act 1868 as a legalised system of kidnapping. He campaigned for ordinary people, for fairness, for democracy and for the common good. He was a Good Samaritan.

Advertisement

While Robert Atkin’s career as a campaigning journalist, newspaper editor and Member of Parliament was cut short, his influence is enduring. He passed the democratic baton to others, like the young Samuel Griffith, who was elected to take his place in Parliament.

Robert made friendships across sectarian divides. A loyal Irish Protestant, Robert made common cause with Irish Catholics, like Dr Kevin O’Doherty who had been transported to Tasmania for being a leader of the 1848 Irish rebellion, to improve the welfare and health of their community. At a time of bitter division between Protestants and Catholics, they formed the non-sectarian Hibernian Society.

The Hibernian Society of Queensland, of which Robert was Vice-President, erected the monument. It states of Robert:

“His days were few. But his labours and attainments bore the stamp of a wise maturity.”

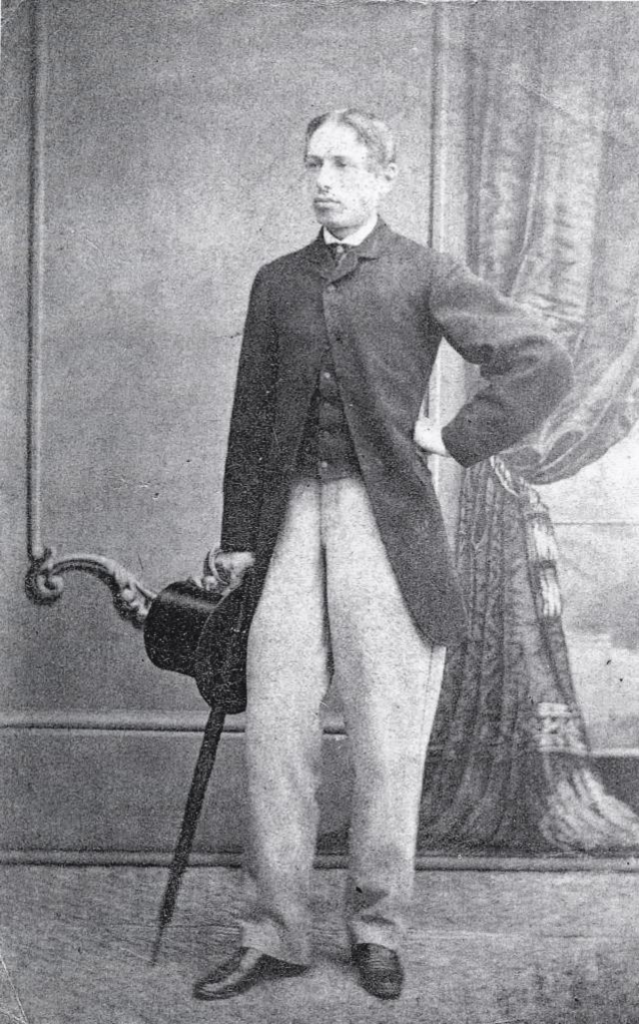

Robert’s sister Grace was devoted to the education of young women in the early years of our state. She started her own school. Her qualities as an educator were recognised by leading educationalist, Sir Charles Lilley, who recruited her to assist in establishing the first Girls Grammar School in Australia. She died on 26 January 1876, aged only 32.

Grace Atkin (1844-1876) (Image sourced from Robert Travers Atkin Restoration Project Facebook page)

As we honour the virtues of Queensland greats Robert and Grace Atkin and their devotion to “initiating a new world for all of us”, what lessons can we learn about stepping across the line to bridge differences?

Chief Justice Susan Mary Kiefel AC spoke at the 29 May 2022 event that commemorated Queensland’s Atkin family

The memorial to Robert Travers Atkin in Sandgate, Brisbane

Author’s note: I would like to thank Justice Peter Applegarth AM for providing the images for this anglican focus reflection and acknowledge his 23 January 2016 opinion piece published in The Australian, ‘Robert Atkin: founding father of social justice’, which I drew upon for this reflection.