Two cheers for techno-optimism, but beware the dangers of techno-enthusiasm

Reflections

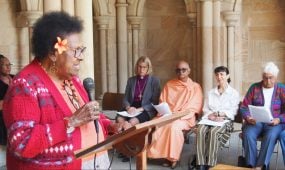

“As well as naïve, the techno-enthusiasm I have described is inadequate because it rests on an incomplete view about the nature of humanity and our place in creation. The implicit ‘naturalist’ worldview of the techno-enthusiast is one that leaves out a transcendental framework, which undergirds our concepts of the common good and human responsibility,” says Provincial Clergy Conference speaker, The Rev’d Dr Chris Mulherin

Technology brings both blessings and challenges: from the wonders of personal computers and smart phones to self-driving cars and now, in the last year, to the amazing ability of large language models and image generation. Free online tools — such as ChatGPT — can write a graduate essay on any topic; a text description can be turned into a new artwork or video; and created-from-scratch human faces (and naked bodies) are often indistinguishable from real people.

This is the age of a revolution in computing known as artificial intelligence (AI). It is also an age of techno-enthusiasm — a time when Silicon Valley billionaires are overwhelmingly upbeat about where the overlapping research into AI and bioengineering will take us.

For example, Ray Kurzweil, computer scientist, principal researcher at Google and techno-enthusiast says that:

“By 2029, computers will have human-level intelligence…expanding who we are…by the 2030s, we will connect our neocortex, the part of our brain where we do our thinking, to the cloud. We’re going to get more neocortex, we’re going to be funnier, we’re going to be better at music. We’re going to be sexier. We’re really going to exemplify all the things that we value in humans to a greater degree.”

How should we respond to advances in AI and associated technologies? More specifically, how should Christians think about and approach the technology tidal wave?

Human ingenuity, powered by the findings of science, has brought unprecedented wealth, health, food security, and welfare to billions. And, although it is not all good news, the common good has been well served by technology.

However, while I am optimistic about the benefits of future technology, I don’t share Kurzweil’s overwhelming enthusiasm. Urgent questions are raised by the pace and power of the current artificial intelligence revolution, which has taken AI from a conversation topic amongst a specialist group of professionals to being a mainstream interest, and indeed tool, for the masses.

Advertisement

There are numerous ethical issues that arise from AI, which are the topic of much discussion; for example, surveillance and privacy, job losses and rogue machine “decision” making, among others. However, I am more concerned about an overarching mindset that I fear dominates the thinking of those who call the shots.

Drawing a sharp distinction between cautious optimism and naïve enthusiasm, I worry about the “techno-enthusiasm” of Silicon Valley billionaires who are often blasé about where AI and associated technologies will take us. And while their enthusiasm is occasionally tempered with the required show of concern, a cynical observer might see this as shrewd marketing to overcome the suspicion that they might be wealthy mavericks playing with toys of unprecedented power.

Techno-enthusiasm is the attitude (or ideology or quasi-religious belief?) that technological innovation will inevitably lead to improving the human condition. Techno-enthusiasts view technology as a powerful problem-solving force that can address issues like poverty, disease, environmental degradation, social inequality, and even human moral failings through genetic engineering. In the extreme, it is a faith that most or all problems have or will have a technological solution — an attitude sometimes called “techno-solutionism”.

Advertisement

One of the characteristics of this view is a strong belief in progress. Techno-enthusiasts are convinced that technology drives continuous improvement in society, as it often has in the past. As well, they are solutions-oriented, seeing technology as the primary means of solving major global problems. And, given a confidence in the almost unlimited potential of technology, we can look forward to a future where technology creates abundance and widespread prosperity, eliminating scarcity of food and other resources. Finally, this enthusiasm also leads to an assumption that the market or governments are responsible for managing the ethical issues arising from technology; for example, witness the decades-long attitude of Facebook, which resisted taking responsibility for teen-harms or fake news and political election manipulation.

However, techno-enthusiasm is a warm, but fuzzy, creed and the devil is in the detail. Who can deny that a better world is a good thing? But when we talk of progress we need to ask, “progress towards what goals?” And when we talk of abundance and prosperity, we need to ask, “abundance of what?” Abundant sustenance for the starving? Abundant toys for the super-rich? What distribution of prosperity will be considered fair? And, if techno-enthusiasm is solutions oriented, which so-called problems are top of the list for solving? While you or I might think malaria or sleeping sickness urgently need solutions, the small group of CEOs and billionaire entrepreneurs who are driving tech forward might have other priorities.

In my view, techno-enthusiasm is a naïve and inadequate mindset.

It is naïve about the realities of human self-interest. And it is naïve in its hopes that human power and ingenuity will eventually bring about heaven on earth. Christians are all too aware of the human propensity for individual and corporate self-deception. Checks and balances, accountability, and ethics committees are all essential controls on our enthusiasm.

As well as naïve, the techno-enthusiasm I have described is inadequate because it rests on an incomplete view about the nature of humanity and our place in creation. The implicit “naturalist” worldview of the techno-enthusiast is one that leaves out a transcendental framework, which undergirds our concepts of the common good and human responsibility.

The unprecedented power of AI, currently in the hands of a few people of a particular culture and mindset, is an urgent reason to address these fundamental questions rather than allowing naïve enthusiasm to dominate the discussion. It is not good enough to leave those who create the AI behemoths to simply assume that theirs is a right view of the common good or the dangers of technology.

For the Church, and the wider community, the challenge is to engage actively and quickly with the promises and threats of new technology before it overruns our ability to thoughtfully manage it. This is the thinking behind the 2020 Rome Call for AI Ethics, initiated by The Vatican, which is an encouraging first step in promoting constructive conversation before the AI horse has bolted. With signatories including Microsoft and IBM executives, the Rome Call highlights six principles that should govern AI development (transparency, inclusion, accountability, impartiality, reliability, and security and privacy).

Meanwhile, within the Anglican Communion, it is reassuring to see the work of the Anglican Communion Science Commission as it too addresses such questions and seeks to lead a conversation that recognises both the blessings and the challenges that technological ingenuity has given to a humanity made in God’s creative image.

May God give us all wisdom to discern the difference between naïve enthusiasm and appropriate optimism.

ISCAST is a network of people, from students and lay people to distinguished academics, exploring the interface of science, technology, and Christian faith. Visit the ISCAST website to find out more.