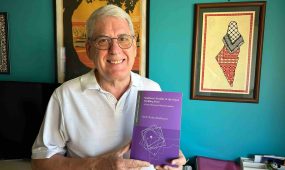

Outspoken: The Life and Work of the Man Behind Those Signs

Books & Guides

The Rev’d Nicholas Whereat of the Anglican Parish of Aspley-Albany Creek reviews the recently published autobiography of the Gosford Anglican Church priest and Senate candidate, The Rev’d Rod Bower

Bower explains in the prologue what motivated him to write his autobiography Outspoken: The Life and Work of the Man Behind Those Signs. It comes from a question that one of his very frustrated parishioners asked him in the street: “Why aren’t you like all the other priests we’ve had here before?” Bower’s response to the irate parishioner was that “…he did what he did because he was a follower of Jesus”. Bower’s life experiences formed a passionate outspoken follower of Jesus, and the book answers the parishioner’s question by Bower telling his story.

Bower’s life got off to a rough start, as he was adopted and there were many ups and downs for the next three decades. In those first decades there were a good deal more downs than ups! In many ways, Bower’s initial statement as he begins his life story is a tragically sad statement: “I have never been anyone’s first choice”. But, it is that very painful experience of being unwanted, or at best a second choice, that has forged the warrior who speaks out on behalf of the underdog.

Our identity and sense of belonging come from loving relationships usually in our family. Bower’s adopted father’s alcoholism and death and the tumultuous adolescence that followed eroded any sense of belonging. Perhaps the saddest part of the story was after his father died and his mum, in deciding to move from the farm to the city, told Bower to shoot his pet dog.

“Toby, my black Labrador-cross, was my constant companion, my best friend and confidant. He wasn’t a particularly good cattle dog – he was far too easily distracted. Other dogs were focused, disciplined and responsive to a whistle, word or even a look. But Toby was faithful, gentle and always by my side (p.30).”

Advertisement

Leaving the farming property was hard and many things needed doing. It was decided the dog could not go to Newcastle, nor stay by himself, nor would he go to anyone else, so the solution was pragmatic: “Go and shoot the dog (p.34).”

Bower never picked up another gun after that day!

Pain and sadness created much of the warp and weave of Bower’s life. Bower recognises the influence of this pain in his capacity to empathise with the outsider. He says:

“While I was raised in a loving family and caring community, being adopted meant that I grew up, at least psychologically, on the edges of society. In the valley where I lived, everyone was related to everyone else, meaning there was a high degree of familial identity. While I was mostly not excluded from this identity, I always felt that totally embracing it would require a lack of integrity on my part, as I truly doubted that I was who I said I was (p.189).”

Advertisement

But life wasn’t all painful, as there were many moments of blessing. Perhaps the most powerful positive experience in Bower’s life came when he and his sister were sent to two quite different churches. Bower and his sister had Religious Education lessons from the local Anglican priest, as well as attending Christian Endeavour run by the Congregational Church. Mr Herman, the leader of Christian Endeavour remains in Bower’s mind a “descent, uncomplicated humble Christian” man. He, along with the two Congregational Church Sunday School teachers, managed to endow Bower with freedom from “moralistic judgementalism and fundamentalist interpretation”. Every second Sunday, the children attended the Eucharist in the Anglican Church. There, Archdeacon Stuart-Fox’s deep love for ritual and worship allowed Bower to develop an appreciation of mystery. Bower was confirmed in that little country church by the same bishop who would ordain him 18 year later. But the next 18 years, starting with the death of his dad, would be a slow and painful journey.

Bower’s autobiography is written in two distinct parts. The first part is the story of much that happened in his life. While, the second part of the book is a collection of short essays, or perhaps conversations. These conversations give the thinking underlying the very short Gosford Anglican Church roadside signs that often go viral on Facebook. Each conversation has a few of the roadside signs peppered throughout the conversation.

The first was the sign that catapulted Bower into Facebook celebrity status: “DEAR CHRISTIANS, SOME PPL ARE GAY. GET OVER IT. LOVE GOD” (p.126). Bower took a photo and uploaded it to Facebook. The Gosford Anglican Facebook page went from 150 followers to hundreds and then thousands. That page has now been viewed over 70 million times. But Bower and his wife did not just get positive feedback. The backlash was horrendous with hate mail threatening them personally. At one stage, Bower deactivated the Facebook page and had a week off to recover the firestorm.

But as Bower explains, it was the story that inspired that first road sign that encouraged Bower and his wife to renew their commitment to using Facebook and Twitter as a way to speak out for the outsider. Bower had been called to do a funeral. At some stage, Bower asked the family if the dying man had been married. The family squirmed and sidestepped the question. Eventually Bower realised the man was gay and his partner was in the next room. The family, fearful that a Christian priest would refuse to anoint the dying man or would castigate him, had asked the partner to stay in the other room. The first road sign and associated Facebook page were the expression of Bower’s deep sadness at such a fear and his desire to tell the Good News of a loving God. He had no expectation of the effect of a simple act of protest. After a while, he realised he had discovered a way to preach to more than just the choir.

There are 26 ‘conversations’ in all, with two thirds being conversations on justice issues, each with the title from the road sign, including marriage equality (“YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES”), refugees and people seeking asylum (“HELL EXISTS AND IT’S ON NAURU”), racism and nationalism (“WE’RE INTO HAIL MARY’S NOT HEIL HITLERS”), climate change (“WE SEEM TO HAVE FORGOTTEN ALL ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE”) , Islam (“BOYCOTT THE BIGOTS AND BULLIES BUY HALAL”), and even borrowing the ‘hallowed’ words of the Anzac tradition in reference to offshore detention (“LEST WE FORGET MANUS AND NAURU”).

The last 10 conversations are reflections on faith – all with a very strong personal touch, giving the reader a strong sense of who Bower is and what makes him tick. Each of the 26 conversations could easily be used as a conversation starter in a group that is willing to discuss controversial issues. But, if you still hold to a taboo on talking about anything to do with religion, sex or politics, most of these conversations will be out for you. I suspect the parishioner who asked “Why aren’t you like all the other priests we’ve had here before?” will now be satisfied with a thorough answer. He may be glad if Bower is successful in his bid to enter politics, as Bower recently announced his intention to run as an Independent Senate candidate in the forthcoming federal election. Maybe then he will be rid of this troublesome priest.

In conclusion, it is worthwhile reading this book to appreciate why Bower is so keen to speak out for the underdog. Bower knows firsthand what it feels like to be the underdog, chosen second or not at all. For me many of Bower’s passionate ‘conversations’ resonated powerfully. Many readers may find the conversations and their titles unsettling, but with insights from Bower’s life you are able to appreciate Bower’s passion, insights and perspective. It is precisely because of this that I would recommend this book. It is essential reading for all who have had comfortable lives in loving families, with opportunities for education and employment in one of the best nations of the world.

Outspoken: The Life and Work of the Man Behind Those Signs is published by Penguin Random House Australia.