A Stage on the Road: St John's Cathedral sermon

Homilies & Addresses

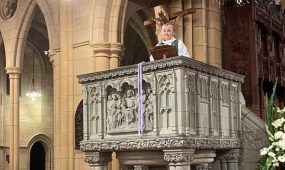

A sermon preached by The Rev’d David Gill at St John’s Cathedral in November during a special evensong commemorating the life of Catholic Bishop Michael Putney and marking the 70th anniversary of the formation of the World Council of Churches

It was 1948. Bitter memories of war were still fresh. Large parts of Europe, Asia and the Pacific had been devastated. The hearts, lives and hopes of millions had been shattered. And now there loomed a new threat. A cold war, that promised more fear, more enmity, more hating.

But something else was happening, too. Something that contrasted dramatically with the world’s anguish. Representatives of 147 Protestant, Anglican and Orthodox churches gathered in Amsterdam to form a World Council of Churches. Since then, please note, the body’s membership has more than doubled – from 147 churches to 348 – and while the Roman Catholic Church remains a non-member there are nevertheless close working relationships.

This was unprecedented. A World Council of Churches? There had never been anything like it. After centuries of religious conflict and after all the blood that had been shed, long separated churches were gathering, ancient hostilities were ending, enemies were becoming friends, reconciliation was happening. Christians, it seemed, were not just talking about unity. They were starting to do something about it.

The World Council’s formation, of course, was not the beginning of the ecumenical movement. Much less was it, in any sense, the movement’s goal.

The Council’s founding general secretary Willem Visser ‘t Hooft, made that point very clearly to the Amsterdam delegates:

We are a council of churches, not the Council of the one undivided Church. Our name indicates our weakness and our shame before God, for there can be and there is finally only one Church of Christ on earth…Our council represents therefore an emergency solution – a stage on the road – a body living between the complete isolation of the churches from each other and the time…when it will be visibly true that there is one Shepherd and one flock.

An emergency solution. A means towards a much greater end. An organisation that like all ecumenical bodies would seek – should seek! – to work itself out of existence.

That was 1948. Today, we give thanks for that “stage on the road” towards Christian unity. But today, we must also ponder: where on that journey do our churches find themselves now?

Seventy years down the track, it is a curious situation. Where the churches are today, ecumenically, is very appealing. It is also, however, utterly unbearable.

Advertisement

Appealing? Yes. Denominational relationships have improved greatly. Old tensions have faded. Churches cooperate on so many fronts. A leader of the Conference of European Churches put it well. “The status quo,” he said, “is all the more pleasant when it is among friends”.

The trouble is, we are tempted to downgrade the ecumenical vision to fit. The influential journalist John Allen exemplified this when he argued, in the National Catholic Reporter, that pluralism is the way of the world, churches should rejoice in the cooperation thus far achieved, and nobody should expect Christian unity this side of the Second Coming.

In other words, what we have is as good as it gets. So forget what we thought was the goal of this journey. Put your feet up and relax. Enjoy this very pleasant status quo.

But, where we are today is also utterly unbearable. For two reasons.

First, our hearts cry out for more.

The late Aghan Baliozian, primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church, was a fine pastor, a dedicated ecumenist and a great friend. While serving the National Council of Churches, I was invited regularly to share in Christmas celebrations at his cathedral in Sydney and then, after the liturgy, speak to the congregation. The Archbishop’s welcome was always “Father David, we welcome you to this church, for our church is your church too”. Note the your.

Advertisement

In 2007 the Uniting Church marked its 3oth birthday. The ABC ran a rather poor Compass program, which included a few seconds of me. Next morning my phone rang. It was Bede Heather, the former Catholic bishop of Parramatta. “David,” he said, “it was good to see you on the box last night. But I thought Compass was a bit unfair to our Uniting Church.” Note the our.

Then there was the gathering, a few years ago, of Queensland Churches Together. Some people were talking with Archbishop Phillip Aspinall about the tough time his church was having over something or other. It was a Uniting Church voice that said, with feeling: “When the Anglican communion bleeds, my heart bleeds too”.

Isn’t that where we are now? The days of ‘us’ and ‘them’ are, thank God, gone forever. We are all simply ‘us’. Oh, we still have those denominational identities. But each label now has an unseen plus sign: ‘Uniting plus…’, ‘Catholic plus…’.

If ever a man embodied the invisible plus sign, it was Michael Putney – brother in Christ, father in God and inspiration in things ecumenical for all of us.

Some years ago, the Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney was facing the impending retirement of Cardinal Ted Clancy. Speculation ran wild about his likely successor. Michael Putney was my candidate. “If you get Sydney,” I told him, “I’ll have to give serious thought to becoming a Catholic”. Well, Michael did not get Sydney – I suspect to his great relief, certainly to Townsville’s – and I have not crossed the Tiber. Yet! But he was that kind of person. He lived the invisible plus sign.

Many have written about the profound implications of the churches’ mutual recognition of baptism – implications that have yet to be adequately worked through. Michael wasn’t content to write and speak about that subject. He lived it. That was his special charism.

We don’t yet have the doctrinal formulae to express it or the organisational relationships to embody it, but in our hearts we know it is true: we belong to one another, because we belong to Christ.

Our hearts cry out for more.

Second, and more importantly, the heart of God cries out for more.

The Gospel is not about being enabled to tolerate our divisions. It’s about the reconciling power of God in Christ that ends them. Our Lord’s prayer was not that His people might be friends, or cooperate, or form councils of churches. It was that they may be one with an intimacy reflecting that of the triune God.

So, how are we to move forward along this road? Some years back, a former general secretary of the World Council of Churches was speaking about the role of the churches in a world of political and religious conflict. One sentence grabbed my attention: “Christians must develop the spiritual capacity to hear and see the grace of God in the other,” he said.

Translate that to interchurch relationships. Christians must develop not the diplomatic skill to charm the other, not the political know-how to manipulate the other, not the worldly power to coerce the other, not the theological clout to convert the other. But the spiritual capacity to discern what is truly of God in the other, the gifts God may be trying to give us through the other.

Such ‘receptive ecumenism’ is a way every church can take further steps on this journey. It shifts the ecumenical problem away from the other – the denomination that’s difficult to get on with, the church that doesn’t think about sex the way we do, the bishop who won’t play ball, the doctrinal stance that seems set in concrete – and focuses the initiative back on us. Not just the experts, the church leaders, the ecumenical bureaucrats, but us, each and every one of us, and on our capacity to discern and receive.

For Christian unity must never be seen as a mere exercise in ecclesiastical joinery. It’s about the transformation of hearts and minds, nothing less.

Which sounds like a big ask. Too big?

Whenever the ecumenical task looks a bit daunting – and when has it not? – we do well to remember what drives it. Not some vague notion that it’s nice to be nice to other Christians. Not some coterie of ecumaniacs with nothing better to do with their time than sit in meetings. Not even the strenuous efforts of things called ‘councils of churches’. What drives it is not us, at all.

For, to adapt some words of George Bernard Shaw, ecumenism is not “a game which we play” but “a game played upon us”. We are not gathering the churches. They are being gathered by our reconciling Lord, to whom in different and faltering ways they are trying to respond.

There will be times, like 1948, when the movement seems obviously successful, and times when it seems to stagnate. Times when it is popular, and times when it recedes into the background. But, in good times and in bad, whether in 1948 or 2018, the movement goes on. As it must, for it is of God.

This night, then, let our hearts be thankful. Yes, for the World Council of Churches. Yes, for Michael Putney. Yes, for all who have been guiding, inspiring, resourcing and supporting our churches for this wonderful journey.

But let us, above all, give thanks to the Lord. Who never abandons His people to their conflicts and failures, who is leading us onwards yet towards the day when there will be visibly one Shepherd, one flock.