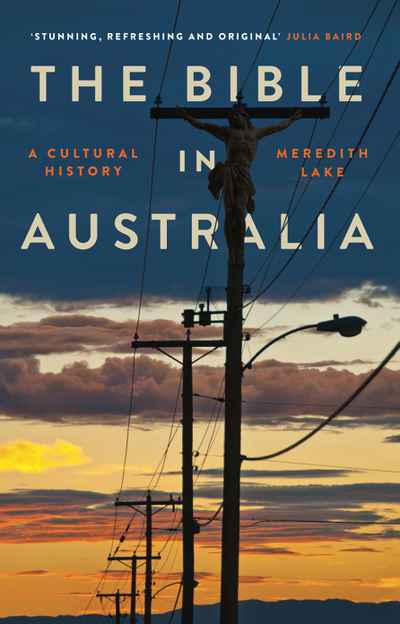

Prize-winning book chronicles Bible's impact on our nation

Books & Guides

The prize-winning book The Bible in Australia: A Cultural History by Meredith Lake chronicles the Bible’s impact on our nation

Julia Baird rightly describes this book as “stunning, refreshing and original”. It uncovers the broad and significant role of the Bible in Australian history since 1788. So many books cover well-trodden paths: this one leads us into new territory.

Meredith Lake shows us the history of the Bible in Australia over the last 200 years as a widespread cultural artefact and a significant influence in the development of society, and notes the proliferation of its words and phrases into the language of everyday life. She finds words from the Bible on the back of a surfie (“My brother’s keeper”), and describes the Bible which James Cook took on the Endeavour, the teaching ministry of Moses Tjalkabota in western Aranda country, the faith journey and teaching ministry of Bessie Lee in Australia, New Zealand and North America, the love of the Bible in many of the early Australian unionists, and the response to the Bible in Australian art, Western and Indigenous, as in literature and music. She points to the impact of the Bible on Australian culture, as central to the liturgy of the Church, as it has been used in personal reading and devotion, and as an instrument of evangelisation.

Meredith Lake, the author of The Bible in Australia: A Cultural History

Kenneth Henderson, an Anglican priest, was the first head of the department of religious programming for the ABC in 1949. Among other programs he included a Daily Devotion and a reading from the Bible six days a week. In 1960, nine out of 10 Australian homes owned a Bible, as well as a cookery book and a dictionary!

Early colonial Bibles were often the gift of Christian organisations, such as the Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK), and the Religious Tract Society (RTS). The interdenominational British and Foreign Bible Society founded in England in 1804 formed an auxiliary in New South Wales in 1817, the oldest continuously operating voluntary society in Australia. Richard Johnston, the first chaplain, brought 100 complete Bibles, 400 New Testaments and 500 Psalters, all provided by SPG.

Advertisement

Of course the Bible has also been used and seen as an instrument of oppression, as one expression of white European arrogance. Lake shows the misuse of the Bible in the Enlightenment theory of terra nullius, and in the capitalist and Enlightenment priority of “improving the land” without regard to the consequences to the environment. We learn that “Bible-banger” or “Bible-basher” was one of Australia’s contributions to the English language!

The book is full of wonderful personal stories of the use of the Bible. Christiana Blomfield encouraged her children to read the Bible in the 1820s:

They came to me for an hour of a morning, when they read a portion of Scripture, which I explain to the best of my ability, and I encourage them to make remarks on what they read.

Mary Gilmour recalled reading her family Bible in the 1870s. She had received her first lessons from it while sitting on her grandfather’s knees.

Barak, an Indigenous leader in Victoria, quoted the Bible in a letter to the Argus in 1889, in an attempt to get justice for his people:

Advertisement

White fellows would not like us to come down to take their land from them and move them out of their homes. We are in a Christian land and ought to love one another with brotherly love (Romans 12:10).

Edward Cole, sceptical Melbourne bookseller, wrote in the 1870s and 1880 attacking the Bible and Christian doctrines. However in 1903 he wrote a series of essays on “The White Australian Question”, in response to the development of the White Australia policy. He refuted it from the Bible: “‘We will not allow any Asiatics or other Coloured People to settle in any part of Australia.’ So say many Australians. ‘God hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on the face of the earth.’ ‘Do unto others as ye would they should do unto you.’ These just and humanitarian doctrines were taught by two Asiatic coloured men, Jesus and Paul.”

World War I Australian Army Chaplain William McKenzie gave out more than 1300 New Testaments in two days at Gallipoli, and reported that “the men rushed these testaments like wolves”.

Lake also points to the fact that the Bible has always had a contested role in Australia, and she covers the decline of church life and of biblical literacy since the 1970s, as well as the recent transformation of the Bible from a printed book to an electronic medium.

It is clear that Australia since 1788 has not been bereft of Christian influence, as this book chronicles the widespread existence, use, and influence of the Bible on individuals, communities, and the nation.

One of the saddest features of this account is the fact that while translation into Indigenous languages was widespread in 19th century missionary work around the world, it was remarkably slow here in Australia.

[In the early 19th century in Macau Robert Morrison translated the Bible into Chinese, and in India William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William Ward between them translated the Bible into 24 different Indian languages and dialects, and compiled dictionaries in Marathi, Sanskrit, Bengali and Punjabi.]

As Lake tells us, translation of the Bible into the many Indigenous languages in Australia was not common. Lutherans and Moravians and Presbyterians made the best early contributions.

Bible translation is essential. As St Augustine wrote, “God seems especially near us when he speaks our language”. And if God speaks our language, then we can pray to him in our language, and we can tell others about him in our own language. Here is Lake’s account of the power of the translated Bible. In 1942 the Nunggubuyu leader Madi Murungun came to a great realisation after hearing the Bible read in his own language. He used to think that Jesus was only a white man’s God, but came to understand that Jesus was also the God of black people. What had changed his mind? “Now I know that Jesus speaks Wubuy.”

The first complete Bible translation into Kriol was published in 2007 [Kriol is a lingua franca created by Indigenous people in northern Australia]. More translation work continues into traditional Indigenous languages.

Throughout her book Lake helpfully distinguishes between a “cultural Bible” and a “theological Bible”. A “cultural Bible” is a book that is revered and valued, which shapes words and imagery of a society, but does not shape the values or actions of the society. A “theological Bible” is a book which continues to shape and challenge the values and actions of a society, and so also shapes the words and imagery. A “cultural Bible” has the form but not the substance: a “theological Bible” has both. Individuals, churches and nations can retain a “cultural Bible” but lose a “theological Bible”.

May God’s words shape our lives, our churches, and our nation.

First published in The Melbourne Anglican on 6 December 2018.