Elly Conway: 'a strong, deadly black' woman’s life on Palm Island

Features

In the spirit of the recent NAIDOC Week theme ‘Voice. Treaty. Truth.’, Elly Conway, the mother of the ACSQ’s Reconciliation Action Plan Coordinator Chrissy Ellis, tells us about her experience and insights growing up on Palm Island under the Aboriginal Protection Act

Please note: First Nations peoples should be aware that this content may contain images or names of deceased persons.

My name is Aunty Elly Conway, I am a ‘Bwgcolman’ Elder born on Palm Island, an Aboriginal mission North-East of Townsville. ‘Bwgcolman’ means Palm Island and is a Manbarra word meaning ‘Many Tribes, One Mob.’ The name was given because under the Aboriginal Protection Act many tribes were forcibly removed from their traditional homelands and sent there. I am a descendant of Kaantju tribe from Coen on my Father’s side and I am a descendant of Pitta-Pitta tribe from Boulia on my Mother’s side.

I would like to thank the Anglican Church Southern Queensland for inviting me to share what 2019 NAIDOC Week Theme –Voice. Treaty. Truth. means to me.

Since British colonisation in 1788, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been denied sovereign rights, control over traditional lands and practising customary laws. In May 2017, the Referendum Council conducted their final consultation with 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community leaders from across Australia to attend ‘Uluru’ National Convention on Constitutional Recognition.

As a collective voice, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people call on the Australian Government to (1) Enshrine a National ‘VOICE’ in the Constitution; and (2) Establish a Makarrata Commission to supervise Treaties and Truth-telling.

(Makarrata – is a Yolngu (yungu) word which means coming together after a struggle to acknowledge the wrong, and putting things right);

Let me begin by sharing my personal story living under the Aboriginal Protection Act on Palm Island and highlight why it’s important to have a National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ‘VOICE’ enshrined in the Australian constitution.

VOICE

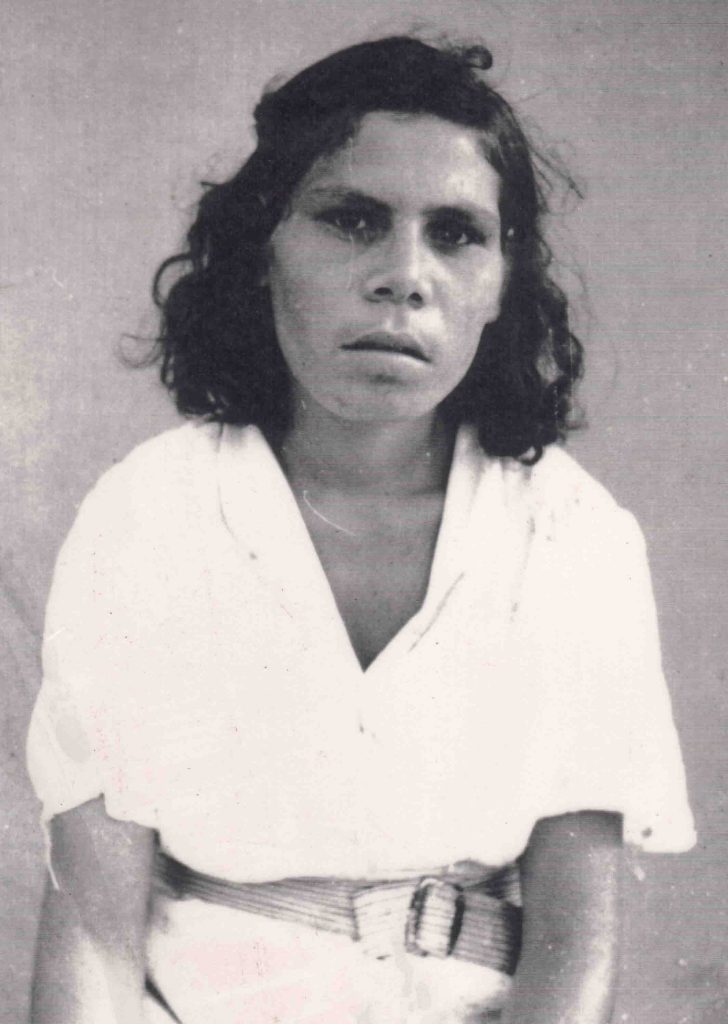

Dolly Creed

My mother Dolly Creed was a Pitta-Pitta woman born in Boulia, west of Mount Isa. My grandmother was a traditional Aboriginal Pitta-Pitta woman and my grandfather was a white man. It is unknown whether this relationship was consensual or whether her children were born out of sexual violence. Given the historical timeline of this nation’s era and events, one can only imagine it was the latter. Under the Aboriginal Protection Act my mother and Aunty Margaret were forcibly removed from their mother because of their fair skin and sent to Palm Island when they were teenagers. My uncle Jack was hidden by his mother from authorities and later raised by another Aboriginal family, the Craigie’s. This is known as ‘Stolen Generations.’

My mother, Dolly worked on Palm Island as a domestic servant and seamstress. She married Harry Wilson and they had four children. Harry was sent to Phantom Island because he had leprosy and never returned. She was left to raise her four children on her own until she met Jim Stanley.

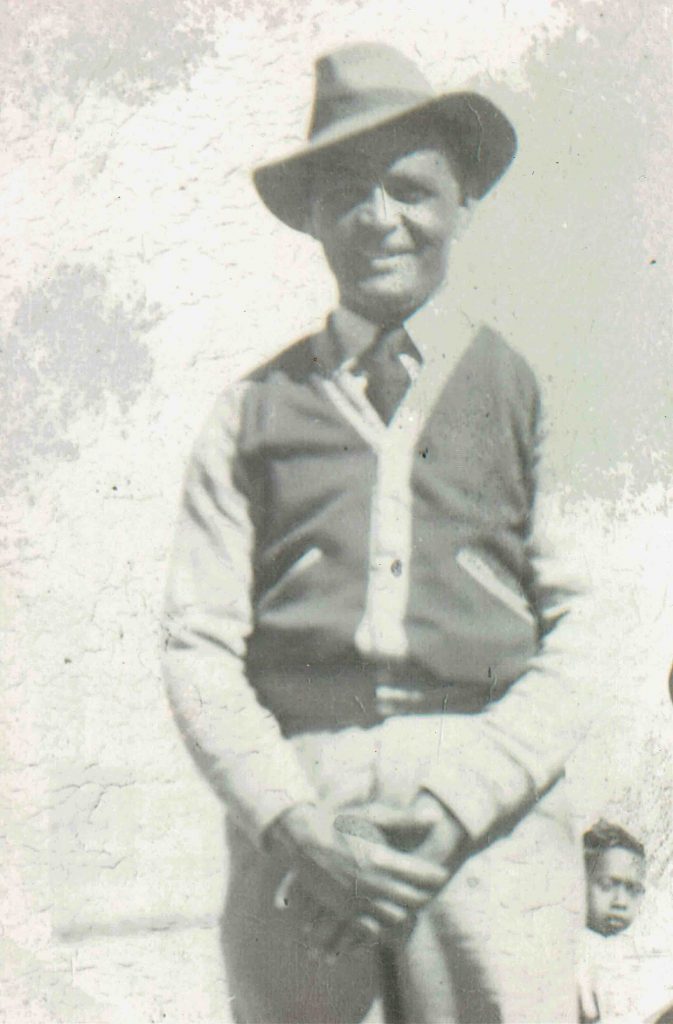

Jim Stanley

Jim Stanley was banished to Palm Island from Cherbourg as punishment and left behind a wife and seven children. The Superintendent has the power to forcibly remove people. My parents had seven children together and married in Palm Island Catholic church after their fourth child. Under the Aboriginal Protection Act men and women had to seek permission from the Superintendent before they could get married.

Palm Island Girls’ Dormitory

Under the Aboriginal Protection Act young pregnant women, unmarried women, young girls were sent as punishment to Palm Island and resided in the women’s and girl’s dormitory. These women and girls were punished for having white blood or deemed by authorities as having so-called parents who were incapable of looking after them. This is known as ‘Stolen Generations.’ My parents were the dormitory managers until the women’s dormitory closed in 1967 and before the girls’ dormitory closed in 1975. When the Aboriginal Protection Act was abolished they relocated to Shorncliffe and became the managers of Opal Guest House, a hostel for Aboriginal men and women.

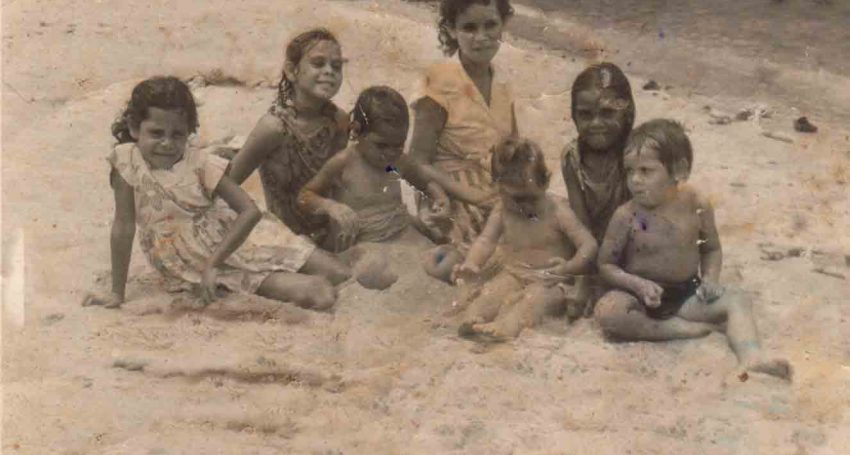

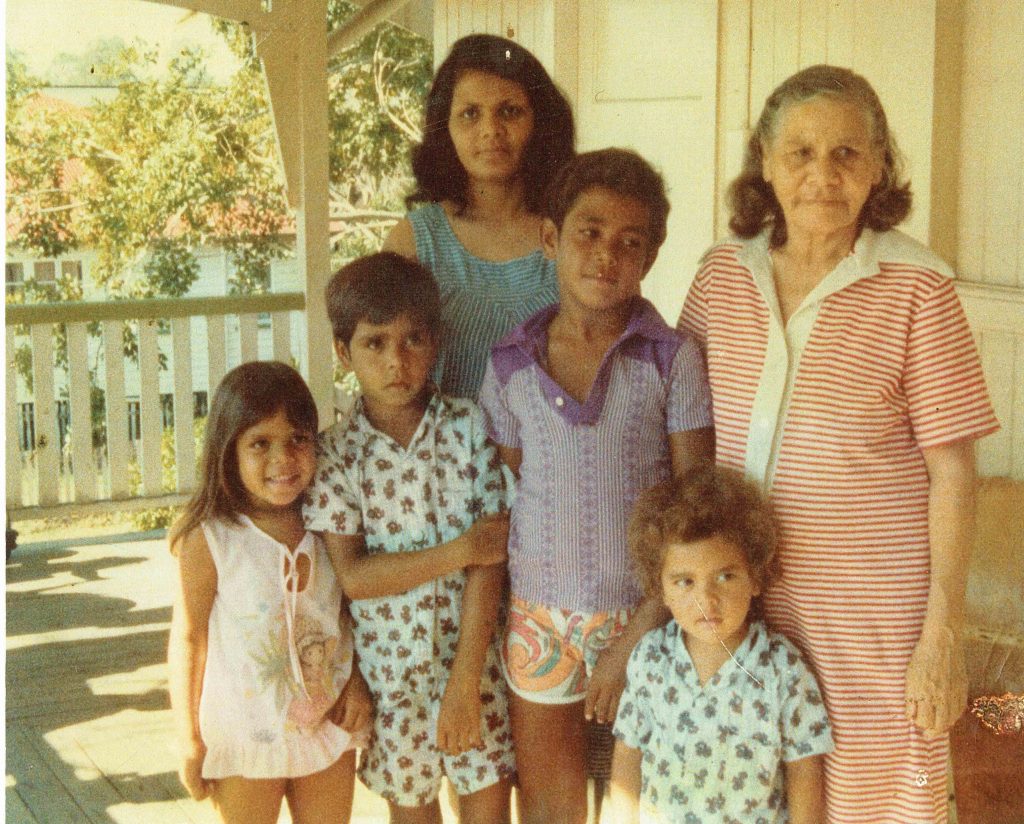

Dolly Creed (mother), Elly Conway and siblings on Palm Island Beach

My Life on Palm Island

As a child living on Palm Island under the Protection Act there was no transport and I walked miles in bare foot to Catholic school escorted by Aboriginal police. Our lives were controlled by a bell which rang to tell everyone on the island when it was time to go to work and when to finish. Once a week I would go to the Ration Shed down the front beach for food. Food was rationed – meat, bread, rice, sugar, salt for the number of people in each family. My mum sewed bags to put the food rations in and a lot of the times rice had weevils. There was a milk shed where we used to get fresh milk in a homemade billy can. If I didn’t get there early before 6am I would miss out.

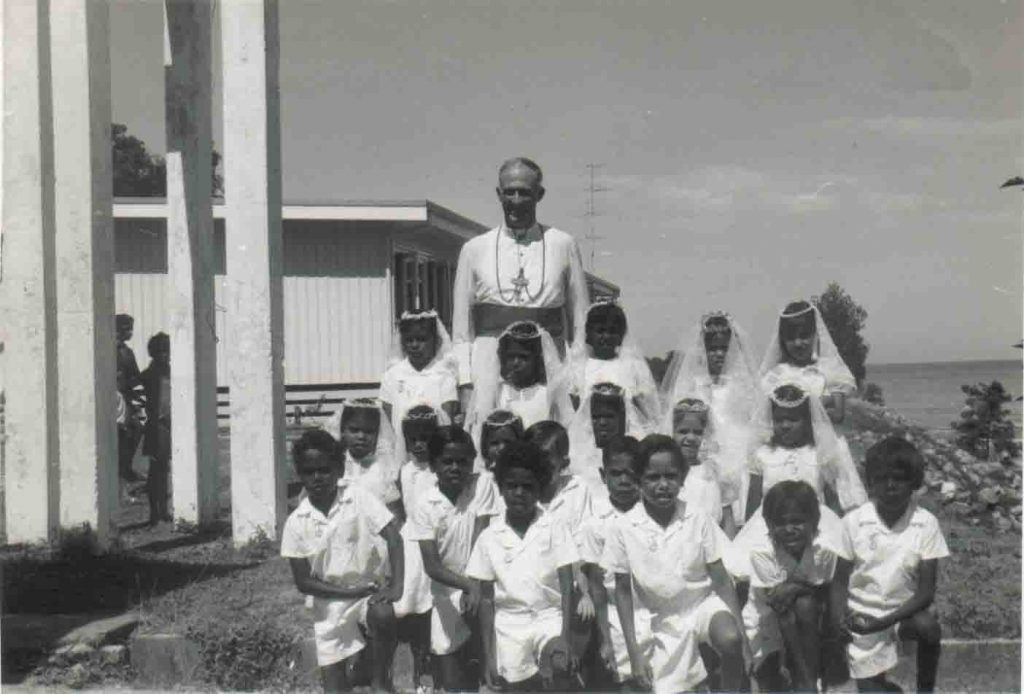

Elly Conway at Palm Island Catholic School: First Holy Communion

I attended Palm Island Catholic School. We only had primary school and went to grade 7 on the island and not everyone had the opportunity to go to boarding school for high school education. White children had their own school on the island and I wasn’t allowed to interact or play with them, we were segregated. I was not allowed to speak my traditional language or learn about my culture, it was forbidden.

Advertisement

Each year only two girls and boys were chosen from the Catholic school and state school to attend secondary boarding school. I was one of the lucky ones who went to St Mary’s College, Charter’s Towers. I only achieved year 10 level education due to feeling isolated, lonely and missing my family – I didn’t want to stay at boarding school to finish year 12. I left school and worked at Palm Island Administration office – telephone exchange, administration and payroll.

Under the Aboriginal Protection Act the Superintendent controlled my wages and pay. I never received Award wages while working and I only received a small amount of my weekly pay. This is known as ‘Stolen Wages’ and I am still seeking recompense for this. I wasn’t allowed to go to other areas on the island, like a day trip to Butler Bay around the back of the island without permission from the Superintendent. I had to get an exemption pass from the Superintendent to travel off the island to Townsville.

Dolly Stanley (mother), Elly Conway and children

A National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander VOICE enshrined in the Constitution means the Australian Government can no longer make laws which are discriminative and unjust. And that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a seat at the decision-making table which affects our people.

TREATY

Australia is the only Commonwealth country that has not entered into a Treaty with its First Peoples. A treaty between the Australian Government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can include the recognition of sovereignty, their relationship and rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Advertisement

TRUTH

During the Referendum Council’s consultations it was identified that Truth-telling about Australia’s colonial history is the foundation to improving race relations and achieving national unity. This requires all Australians to acknowledge past injustices caused to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Sharing my story with you today is a lived-example of Truth-telling.

In concluding, I wish to encourage the Anglican Church Southern Queensland, non-Indigenous children, young people, men and women to find ways to learn about Australia’s Aboriginal history and support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and our rights to recognition, truth, justice and healing. Thank you…

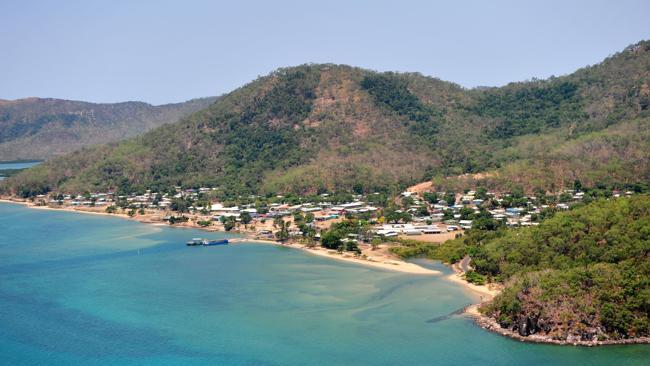

Palm Island

‘Voice. Treaty. Truth’ poster