Miss Bedford and Dr Cooper – pioneering Queenslanders and St Mary’s parishioners

Features

Dr John Earwaker from St Mary’s, Kangaroo Point tells us about Dr Cooper and Miss Bedford, two pioneering locals and devout St Mary’s parishioners who were decorated for their courageous service in World War I and whose unique legacies live on today

The first church on Kangaroo Point was a small wooden building in John Street (now Rotheram St) consecrated in 1849. As the site was flood prone, in 1860 a parcel of land on the cliffs was allocated to the church. In 1862 the first incumbent parish priest, The Rev’d James Moffatt, built a house on the land adjacent to that site, residing there for three years. During the next 60 years, the residence changed hands three times and served as a town house for two prominent pastoral families. In 1926 it was purchased by Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford, known in their beloved wider community as Dr Cooper and Miss Bedford.

Dr Cooper and Miss Beford took up residence in St Mary’s rectory, circa 1930 (Courtesy of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

So, who were these two women and what brought them to St Mary’s? From the outset they had much in common. They were born in England in 1861 and lived in Chatham, Kent. Both were from large families whose parents shared a common belief that every woman’s vocation was marriage, but that whether married or single, the home should be her world. A lifelong friendship was forged between the two women following a chance meeting in the deanery of Rochester Cathedral in 1883. Common interests were soon apparent, including a yearning for a broader education. Despite the similarities they shared, the women were very different in personality. While Lilian tended to be brusque, introverted and no-nonsense, Josephine was known for her warmth, exuberance and joy.

Advertisement

With Josephine as her chaperone, Lilian successfully completed her medical degree whilst her companion embarked on a life of community service, initially as a volunteer at a foundling hospital. In 1891 they arrived in Brisbane where Lilian had taken an assistantship in a general practice. Being the first female doctor in Queensland, Lilian was confronted by significant prejudice, not only from the medical profession, but also from the general public. She had to combat prejudice and even hostility from men of her profession, as well as an innate mistrust on the part of the public generally as to a woman’s capability in the field of medicine and surgery. Their hostility was not the result of jealousy, as many of her adherents averred, but rather from a deeply rooted prejudice against women departing from what they considered was her sphere in life. However, in a space of 10 years Lilian and Josephine swept away this prejudice, winning people over with their kindness, community spirit, faith and sheer hard work.

To mark the turn of the century, a significant history of Queensland was compiled, including biographical sketches of 159 notable men of the time in Queensland. The following extract is from the sole full-page entry devoted to a woman:

“Lilian Cooper met a large amount of old fashioned prejudice not only amongst the general public but also amongst her professional brethren. How she met and swept away this prejudice, or compelled to hide its diminished head is well known amongst all classes of the colony.”

Advertisement

Lilian established a successful home visit service from her main surgery. Lilian rode a bicycle for her house calls in town and would drive long distance via horse and buggy for her bush rounds. Later, she was one of the first women in the state to drive a car, and was a foundation member of the RACQ. Her car was dubbed The ‘Yellow Peril’ by locals, ‘yellow’ for its colour, and ‘peril’ for Lilian’s lead-footed driving. She was a foundation fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in 1928, and was elected to the local branch of the British Medical Association (BMA). Lilian was appointed to the staff of the Children’s Hospital and the new Mater Misericordiae Hospital at South Brisbane, an association which was ongoing for the rest of her professional life.

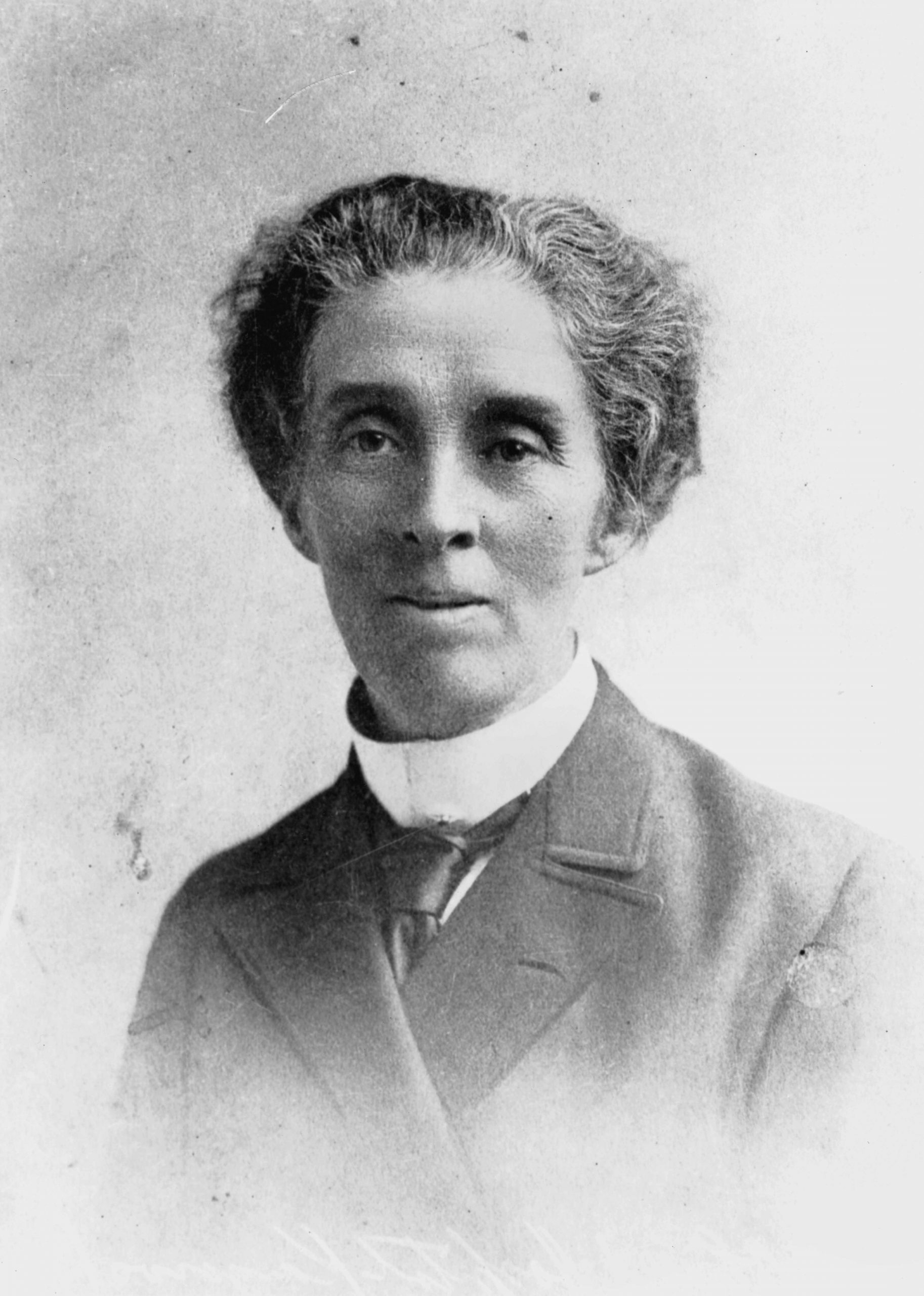

Dr Lilian Cooper in 1927 (Courtesy of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Josephine, however, had no need to work for a living and with no professional ambitions, she turned her considerable intelligence and organising ability to charitable work. She was appointed to the all-female management committee of the Children’s Hospital in 1894, and was active in the affairs of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty. She was a councillor and representative at the inception of the National Council of Women in 1904. This forum discussed important social issues and was an ideal platform for both women to pursue the social justice agenda in which they believed so passionately.

In 1904, and again in 1912, the women made return visits to family in England, during which they gained further experience in England and the United States. Whilst Lilian was learning of the latest in surgical techniques, Josephine was researching family welfare programs and the development of public recreation parks and playgrounds. This latter interest began with Josephine’s voluntary work in London. In 1912 she convened a committee of the Playground Association, which was subsequently responsible for the establishment of playgrounds throughout Queensland.

In 1907, both women were members of a committee formed to address the issue of mothers and their children, which led to the inaugural meeting of the Queensland Creche and Kindergarten. At all times Josephine maintained hands-on involvement. She was a member of the original executive committee and was the treasurer in the early years when money was so scarce she was forced to make a house-to-house canvass for funds to pay the children’s weekly milk bill.

In August 1914 the Scottish Women’s Hospital movement was established to provide mobile hospital units for the treatment of wounded soldiers in World War I. In 1915 the two women responded to a call from the Scottish Women’s Hospital movement for volunteers to serve near the frontlines in Macedonia. They were part of a contingent of 60 people staffing a 200-bed facility under canvas on the front line – Lilian as one of three surgeons and Josephine in charge of the ambulance fleet. In the first three months of 1917, there were 1,840 ambulance cases; 152 admissions; 144 operations and only 16 deaths. Josephine was in charge of the ambulance fleet of 12 converted T-model Fords. She was able to keep them on the road under such rugged conditions with her uncanny ability to source spares throughout Macedonia earning the title of ‘Miss Spare Parts’.

For their outstanding service, they were both honoured by the Serbian government with the Order of St Sava, with Josephine wearing her medal when she marched in Brisbane’s 1918 Anzac Day parade.

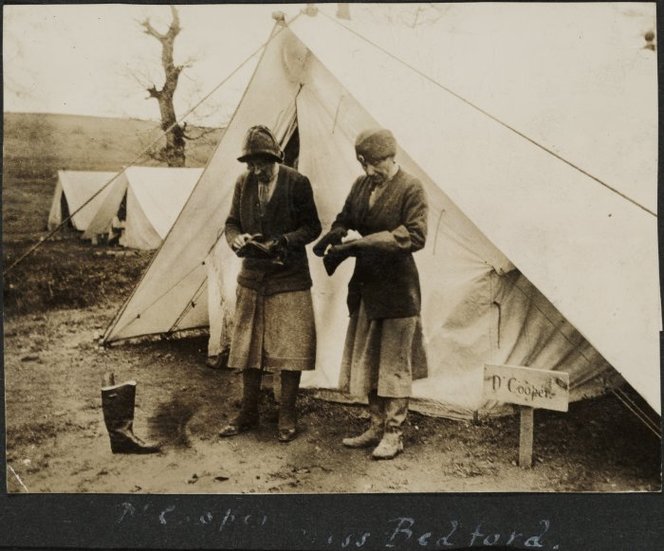

Dr Bedford and Miss Cooper volunteered at Ostrovo Hospital during World War I, circa 1917 (Courtesy of the Queensland Women’s Historical Association)

Dr Cooper and Miss Bedford cleaning their boots in Ostrovo in 1917

(Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, The National Library of New Zealand)

They returned to Brisbane in 1917 – Lilian resuming a busy surgical practice at the Mater Hospital, and Josephine involved in her committees, both the Creche and Kindergarten committee, and as the honorary administrator of the Playground Association. During the influenza pandemic in 1919, the Paddington crèche was closed and converted to a hostel for the infants and young children of infected parents. Josephine was frequently seen transporting the children from the emergency accommodation to an isolation hospital. Subsequently, during the Depression the creche was again used to assist badly affected families in supplying essentials to the nearby Victoria Park camp for itinerant workers. She cherished her naval heritage and had become known affectionately as the ‘Little Admiral’ for her gently imperious manner, which was difficult to challenge (and likely because she was the daughter and granddaughter of Admirals).

In 1926 they renovated Old St Mary’s, to include consulting rooms for Lilian, and a study for Josephine with a personal library well stocked with books on sacred scripture. There was an extensive garden overlooking the river, which provided an ideal venue as a focus for the activities and meetings of the organisations they had been committed to for so long. They were devout St Mary’s parishioners and regarded the Warrior Chapel as their refuge for worship and reflection. The silky oak altar and the centurion window above were subsequently gifted by Josephine in memory of Lilian, with Lilian’s Serbian medal now displayed below the window.

Warrior Chapel altar at St Mary’s

Centurion Window in the Warrior Chapel at St Mary’s

Lilian died in August 1947, aged 86. She overcame discrimination and hostility from her medical peers and the mistrust on the part of the public through her skill and devotion to her work, thereby advancing the cause for women whose franchise was a burning question at that time.

Following Lilian’s death and 61 years living together, Josephine established a charitable trust which decreed that the land be maintained in perpetuity for a hospice for the sick and the dying to commemorate the life of Dr Lilian Cooper. With their close association with St Mary’s, she initially put her proposal to the Church of England, but they lacked the resources to fulfil the terms of the trust. Conscious of Lilian’s long association with the Mater, she then approached the Catholic Sisters of Mercy. However, their priorities were with other projects and so they declined. The Catholic Sisters of Charity were able to comply and Mt Olivet Hospital, now St Vincent’s, was established.

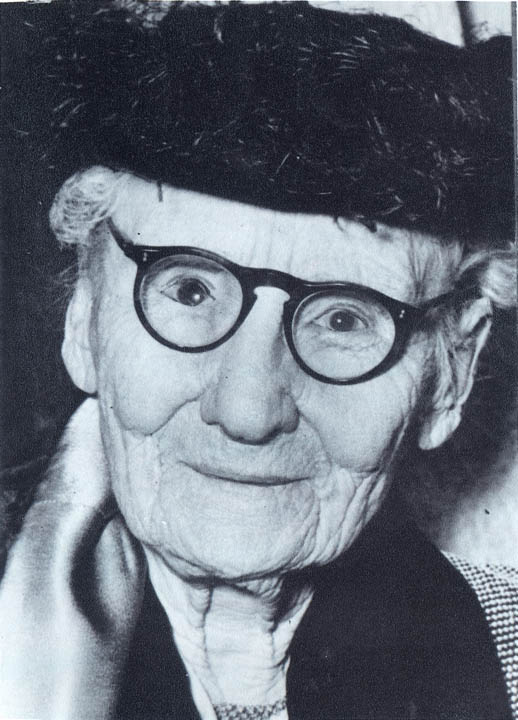

Josephine died aged 94 in December 1955 and was laid to rest in Toowong cemetery by the side of her lifelong friend. Josephine was remembered for her great love for humanity, particularly for children. Her benevolence and charity knew no bounds. Few women have done more good for their community than she, and her good works live after her.

Josephine Bedford in 1954 (Courtesy of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Josephine had an abiding love of trees, particularly for a large weeping fig tree in the grounds of Old St Mary’s. When informed by the Mother Superior of its impending demise, she was sanguine saying “I thought it would be nice for you to sit under in the evenings after your work. But what is a tree compared to what this building [the hospice] will mean to people.” It was therefore fitting that on 25 March 1956, a bottle tree, renowned for its longevity, was symbolically planted in the grounds of Newstead House in Miss Bedford’s honour.

‘The Bedford Tree’ was planted at Newstead House in Josephine’s honour

Dr Cooper and Miss Bedford’s extensive community and social justice work was a natural extension of their faith and their desire as devout Christians to live the Gospel in their daily lives. Their combined headstone reads “God is Love” and “They are thine, O Lord, Thou lover of souls” – Wisdom 11.26. To this day, visitors leave beads and pebbles to remember and honour the two women.