The National Apology and Reconciliation: why are they important?

Features

“Everyone impacted by the Stolen Generations and government policies of forced labour needs healing, and for this to happen, the truth of our stories needs to be told and heard,” says RAP Coordinator Sandra King OAM, as the anniversary of the National Apology is marked on 13 February

Please note: First Nations peoples should be aware that this content may contain images or names of deceased persons.

Throughout my years growing up as a proud Aboriginal woman, I had no knowledge of the Stolen Generations. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that I started to hear bits and pieces, which led to some confusion as to why I hadn’t heard about it and why it wasn’t discussed in my community. After many conversations with my Elders, I was embarrassed to know not a thing and I needed to learn more of this disturbing history. Around the same time, I attended a meeting with an organisation called Link Up, an organisation dedicated to finding and reuniting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, known as the ‘Stolen Generations’, who were separated by racist government policies, and other complicit organisations including churches, between 1910 and the 1970s. To my surprise, I met my cousin Beverley who was heavily involved in establishing Link Up.

Having conversations about the Stolen Generation is part of healing the heartache, but at the same time I am stunned when our Elders still sometimes shut down conversations when having yarns with younger ones, like myself, about this period in our history. The humiliation and pain experienced by community members who are part of the Stolen Generations, including elders, still makes conversations incredibly difficult.

I went to Cherbourg, an Aboriginal Mission in Burnett, in the early 1990s to present to the community where a couple of the Elders, as is customary when Aboriginal people meet each other, asked who my family was. When I responded, they were excited to find out who my father was and to make a connection with my father. I asked them ‘How do you know my dad?’ and they said, ‘Oh, Charlie [my father] and his brother Raymond were up here with their family.’ They then saw the puzzled look on my face and quickly replied, ‘That was a long time ago!’ and changed the conversation. The puzzled look on my face was due to not knowing that my father had been on the mission.

Upon returning home, I asked my father about my conversation with the Cherbourg Elders and he initially responded by finding out what they had said, then replying, “Yeah, daughter, that was a long time ago” and then he promptly changed the topic of conversation. I left it at that and continued my yarn with Elders and community, but surprisingly not with my own family.

Then two and a half weeks before the National Apology to the Stolen Generations speech of 13 February 2008, my father told me that Link Up had asked him if he wanted to go to Canberra for the National Apology. I was surprised and stated, ‘That’s for the Stolen Generations, Dad. Why are they asking you if you would like to go down to Canberra?’ My father replied, ‘Ugh daughter, sit down, I’ve got something to tell you, but I need to get some papers first!’ I will never ever forget that moment…I was in complete shock.

Advertisement

My father presented papers on his family and told me that he and many other family members had been forcibly removed from their homelands and families. He had kept this secret for over 70 years and now he felt it was time to tell me what happened with his family in 1935. For him, I saw it as a time to try and heal his heart and let go of the secret.

Linked to the Stolen Generations was the practice of ‘rounding up’ adults, sometimes whole families, from the late 19th century to the 1970s, and using them for forced/slave labour. During this period, if government officials deemed Aboriginal persons to be disruptive in any way, it was common for them and their families to be removed from their land and put into forced labour.

In 1935, my grandfather, nanna and dad and most of his siblings were escorted off their ancestral land on Stradbroke Island and taken to Cherbourg because my grandfather was deemed by the government to be “a menace to the harmony of Dunwich” and of “truculent and quarrelsome behaviour”. Consequently, my grandfather lost his right to be a proud and strong Aboriginal man, husband, father, leader and worker, and was forced to be a ring-barker under the control of the Queensland Government’s so-called Aboriginal Protection Act. He applied for an exemption (to be released from the Act) several times; however, his applications were rejected, which led to him dying by suicide in 1938.

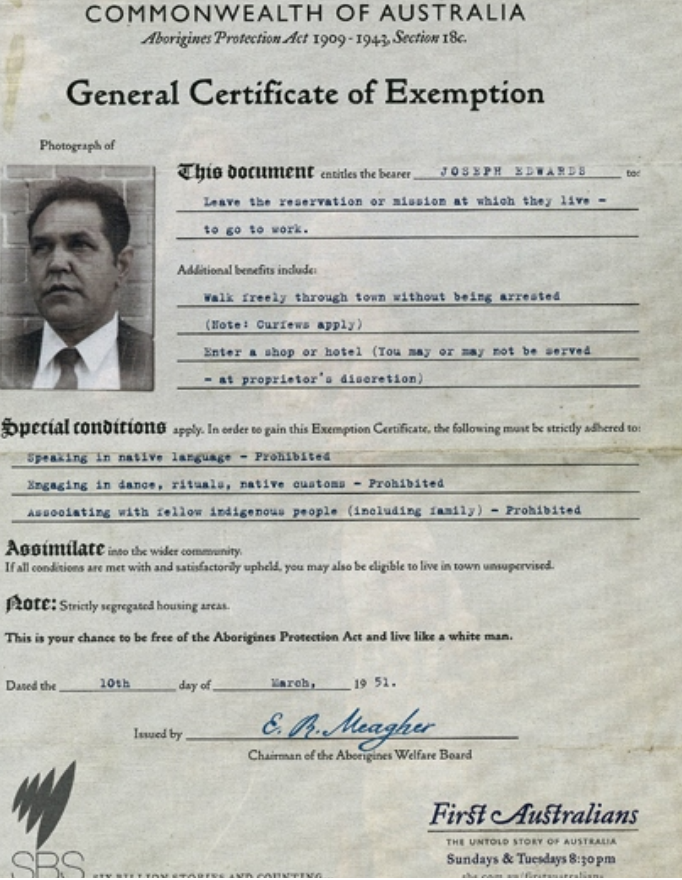

A sample General Certificate of Exemption outlining the rules an Aboriginal man named Joseph Edwards had to abide by

After his passing, Nanna fought to get an exemption, which was granted, but Nanna could only leave Cherbourg with her two youngest children. My dad, who was nine years old and the third youngest, and his older siblings were forbidden to go with her. The siblings were also confined to separate dormitories, one for the girls and one for the boys. The abuse they experienced was hard for Dad to talk about, but I knew he wanted me to record his memories of those horrific days of his young life. I asked why he had kept it a secret for so long and why he hadn’t spoken about it earlier. Dad had promised Nanna not to say anything, as she had feared the family would be taken again and sent back to Cherbourg. Dad told me that as part of the exemption agreement, Nanna was forbidden to return to Stradbroke Island, mix with family or other Aboriginal people, or talk about what had happened in Cherbourg and why they were sent there. Nanna passed away aged 99 years, and my Dad kept his promise to his much-loved mum. Dad copied documents from the archives to pass on to me and to my cousins, as most of them were not aware of what had happened. I now understand why my father never trusted government officials or departments, police and politicians. There is more to this story, but I just can’t discuss it as it is too upsetting. However, I feel Australians need to be aware of the trauma that our family, other families like ours and our Elders have experienced, and to accept the truth of Australia’s dark history.

Advertisement

When my father told me his story, he did his best to remain strong but eventually he had to walk away to compose himself.

Everyone impacted by the Stolen Generations and government policies of forced labour needs healing, and for this to happen, the truth of our stories needs to be told and heard. The National Apology has been acknowledged and accepted by our First Nations peoples. Now we are asking you to work with us to right past wrongs, which continue to affect us today, in order to reach Reconciliation.