Raisin' the curtain on the not-so-humble hot cross bun

Features

“While the spiced bun’s popularity has been on the rise since medieval times, discussions about its origins quickly peel off into a hotly contested debate,” says anglican focus Editor Michelle McDonald, who asks, “How do you HCB?” and “Can you please send us your favourite recipe?”

Hot cross buns, or ‘HCBs’ as they are increasingly called, are traditionally eaten on Good Friday.

The buns are made of sweet leavened dough balls, often filled with currants or raisins or mixed peel, flavoured with aromatic spices, glazed and marked with a cross on top (variously formed by knife scores, a yeast glaze, pastry strips or piping) before being popped into the oven.

Much has been written about this delicious ever-evolving and, as it turns out, historically contentious treat.

For Christians broadly today, the cross on top symbolises the cross on which Jesus was crucified, with others additionally noting that the bun’s spices recall those used in Jesus’ burial.

While the spiced bun’s popularity has been on the rise since medieval times, discussions about its origins quickly peel off into a hotly contested debate.

Hertfordshire St Albans Anglican Cathedral folk claim the pastry as their own, calling it the ‘Alban Bun’. It is said that in 1361 a St Albans Abbey monk, named Thomas Rocliffe, created an original recipe that remains a strict secret, but which we know includes flour, eggs, fresh yeast, and spices such as grains of paradise (a species in the ginger family).

Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans, Hertfordshire, home of the ‘Alban Bun’

The Redbournbury Mill, which was the Abbey’s mill for half a millennium before English, Welsh and Irish monasteries were disbanded between 1536 and 1540, recommenced its milling services for the Cathedral, and since 2005 has also been operating a bakery that produces the Alban Bun. The mill baker is faithful to the original recipe, only adding additional fruit, and continuing the tradition of scoring, rather than piping or otherwise forming, the cross symbol.

Advertisement

Rocliffe distributed the aromatic treat, along with some wine, on Good Friday, which was then known as the ‘Day of the Cross’, to Hertfordshire locals who were living in poverty and who came knocking at the Abbey for sustenance. The gesture became so popular that Rocliffe continued baking the buns annually. Town talk led to the tradition soon spreading, with various imitations necessarily created due to the monks keeping the original recipe a secret.

This history is confirmed by a recent Herts Advertiser piece stating that, while the original source of the bun is still being investigated, in 1862 the same newspaper wrote:

“It is said that in a copy of ‘Ye Booke of Saint Albans’ it was reported that; ‘In the year of Our Lord 1361 Thomas Rocliffe, a monk attached to the refectory at St Albans Monastery, caused a quantity of small sweet spiced cakes, marked with a cross, to be made; then he directed them to be given away to persons who applied at the door of the refectory on Good Friday in addition to the customary basin of sack (wine). These cakes so pleased the palates of the people who were the recipients that they became talked about, and various were the attempts to imitate the cakes of Father Rocliffe all over the country, but the recipe of which was kept within the walls of the Abbey.’ The time honoured custom has therefore been observed over the centuries, and will undoubtedly continue into posterity, bearing with it the religious remembrance it is intended to convey.”

Advertisement

The English Year explains that the first definite record of the hot cross bun is found in the 1733 text, Poor Robin’s Almanack:

“Good Friday comes this month, the old woman runs

With one or two a penny hot cross buns”

However, other sources suggest that the idea of marking a bun with a cross had been around long before Rocliffe or Poor Robin’s Almanack.

Much of the international Greek community and other sources acknowledge that the modern HCB has a precursor of pagan origins pre-dating Christ by hundreds of years. For example, according to the Hellenic Community of Ottawa, the Ancient Greeks carried on the Egyptian custom of inscribing the surface of festival cakes with sacrificial symbols, such as oxen. The Ancient Greeks reportedly offered their cakes to their lunar deities in a similar fashion, calling the cake a boun, derived from the word bous which means ‘ox’. Thus, some suggest that the etymology of the English word ‘bun’ is derived from Greek, while others suggest that ‘bun’ is of unknown origin, having only been documented since 1371.

Over time, the oxen symbol was replaced with a large cross, symbolising the moon’s quadrants, and offered by pagan temple worshippers. Ancient Romans and the pagan Saxons likewise reportedly adopted this tradition in their public sacrifices, with the latter using the small crossed cakes in the worship of Eostre, the goddess of spring and fertility. By the way, some, including St Bede the Venerable, have suggested that ‘Eostre’ is the derivative of the word ‘Easter’; although, Encyclopaedia Britannica states that broad consensus now holds the view that ‘Easter’ is derived from the Old High German eostarum meaning ‘dawn’, but let’s save that etymological hot potato for next year’s Lenten season.

Portrait of Bede writing, from a 12th-century copy of his Life of St Cuthbert (Image courtesy of British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26, f. 2r)

The hot cross bun has enough going on when you consider other historical controversies, including Queen Elizabeth I’s 1592 banning of the bun, except on Good Friday and Christmas Day and at funerals, due to the belief that the humble HCB had spiritual healing properties and was thus too special to be eaten on any other day, with recalcitrants forced to surrender their buns to people desperate for food.

Queen Elizabeth I got cross and banned the bun in 1592, except on Good Friday and Christmas Day and at funerals, due to the belief that the HCB was more holy than humble

Indeed, people were so convinced of the bun’s supernatural powers that they were hung on house beams to ward off evil spirits and have been used as protection from shipwreck.

There’s even a pub in London’s East End called The Widow’s Son, named after a widowed mother who lived on the pub’s site and who, in 1824, baked a batch of hot cross buns for her son who was due home from sea that day. He never returned, but she continued to bake a bun for him annually, until she died, always hanging it in the kitchen, too grieved to throw it out.

The Widow’s Son pub in Bromley by Bow (Image courtesy of https://spitalfieldslife.com/2012/04/06/the-widows-buns-at-bow-2/)

Every Good Friday, a Royal Navy sailor adds a new bun to the collection hanging in the pub, with sailors from around the UK coming to pay their respects to the mother and her seafarer son.

Alan Beckett hangs a hot cross bun in The Widow’s Son pub on Good Friday, 4 April 1958 (Image courtesy of https://spitalfieldslife.com/2012/04/06/the-widows-buns-at-bow-2/)

Whatever the origins and history, most, if not all, agree that these traditional Easter pastries are yummy in one form or another, whether made with or without dried fruit and peel, or with newer alternative ingredients, such as chocolate chips. And, whether eaten with butter, Nutella, peanut butter, honey or jam, or just on their own.

So, tell us, how do you HCB? And, if possible, please send us your favourite recipe. Comments and posting of recipe links or uploading of recipe pics can be actioned via this ACSQ Facebook post.

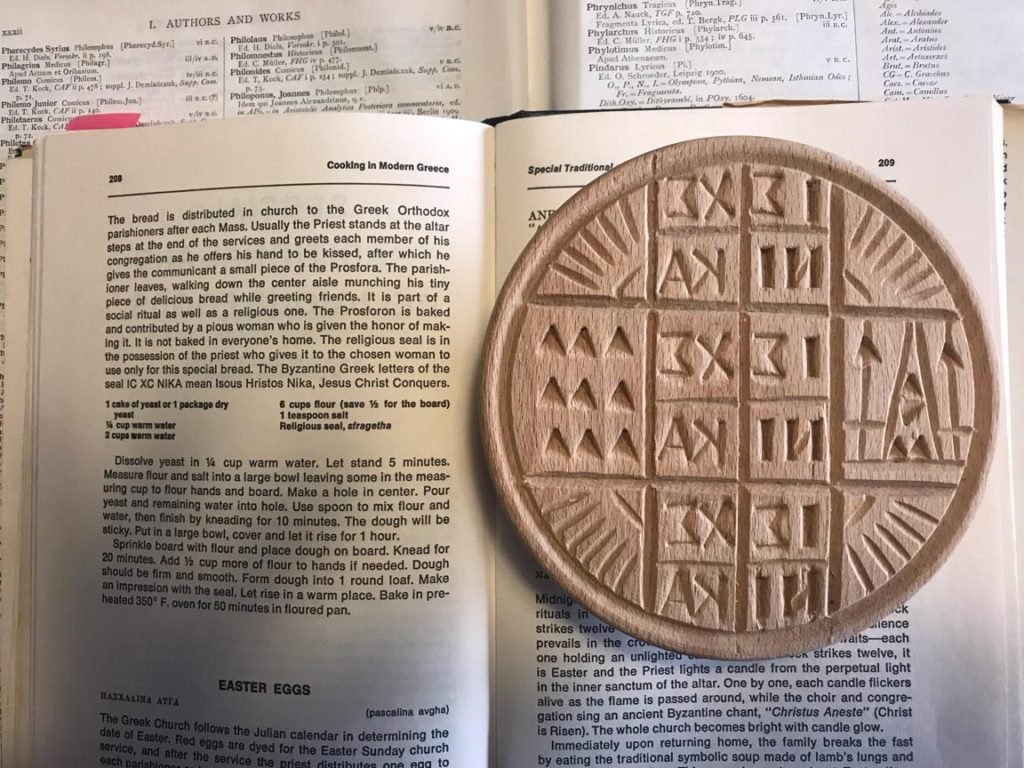

Editor’s note 15 May 2020: Thank you to reader, James McDonald, who upon reading this feature emailed the Editor a picture of this modern-day Greek bread stamp, which he said is used at Easter and on bread that is delivered to the doorsteps of people invited to island weddings:

“The phrase means ‘Jesus Christ conquers’. The I and the sigma are the first and last letters of ‘Jesus’. The X and the sigma are the first and last letters of Christos. The word Nika means conquers. The writing is backwards, obviously, because of the stamping reversing the letters, but the article left of the stamp explains the wording” (Reader, James McDonald)

If any reader can translate the other symbols on this bread stone, please email the Editor at focus@anglicanchurchsq.org.au.