Did anything good come out of the Middle Ages?

Features

“Anglicans, too, are often reluctant to affirm the value of the Middle Ages…This is unfortunate. For missing out nine whole centuries of Christian life not only creates serious gaps in understanding Christian development – it also risks failing to appreciate important Anglican features and spiritual treasures fully,” says The Rev’d Dr Jo Inkpin

The ‘Middle Ages’, and the term ‘medieval’, is frequently used as a byword for ignorance and brutality. Indeed, many associate it with religious oppression and corruption. Anglicans, too, are often reluctant to affirm the value of the Middle Ages. We are not helped by over-significance sometimes given to the 16th century Reformations and the early Church (up to about 600 CE). This is unfortunate. For missing out nine whole centuries of Christian life not only creates serious gaps in understanding Christian development – it also risks failing to appreciate important Anglican features and spiritual treasures fully. Arguably, in the 21st century, in our so-called post-modern age, recovering these is vital as faith is reshaped afresh.

‘Nasty, brutish and short?’ – beyond medieval myths

Many medieval myths undoubtedly need unpacking. For far from a hideous uniform time of darkness, the period 600-1500 was incredibly diverse and creative. Yes, levels of health, education and democratic life that we take for granted were lacking. However, those modern elements largely emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Reformation era certainly brought no significant changes of this kind. Ordinary people’s rights were actually eroded then, as the power of nation states headed by autocratic elites increased. This included the growth of the royal prerogative, centralised bureaucracy and standardised languages, which undermined local courts and laws and marginalised those with regional languages and dialects. Above all, with the enclosure of common lands, poorer people increasingly lost capacity legally to forage for food, graze animals of their own and collect fruits and firewood.

Heretical movements also endured persecution in the Middle Ages, yet the most horrendous Christian wars of religion occurred in the 17th century. The violence of the medieval Crusades similarly impacted the relationship between Christians and Muslims. However, the first destructive impacts of European imperialism, ‘backed up’ by Christian religion, began much later on the Reformation’s eve, and still more in the 19th century. Care existed for the poor and otherwise challenged, if on a very paternalistic basis. Peasants were also not just revolting or unsophisticated – they were very aware of legal rights, or lack thereof, and customs. Punishments, if sometimes cruel, had clear proportionality. Anti-semitism, witch-hunts and oppression of minorities are also part of the medieval story, but the degree of such inhuman activity pales in scale compared to that inflicted later.

Crusaders embarking for the Holy Land

Encaustic tiles (1250–60) bearing the images of King Richard I (1157-1199) and Saladin (1137/1138–1193) in mounted combat during the Third Crusade of 1191 (Battle of Arsuf). Saladin was a Muslim military and political leader who, as Sultan, led the Islamic forces during the Crusades

Overall, therefore, if we could time travel, we would recognise much of our own humanity. Our greatest challenge would be sensory shock, not least that of smell and feel! Religiously speaking, we would also encounter a different age, but with some familiar, and, arguably, some refreshing features. Four particular aspects might help us: the physical and symbolic character of medieval ecclesiastical buildings; the variety and depth of medieval thought; the extraordinary panoply of prayer and spirituality; and, the order of the Church itself.

Advertisement

1. Christian faith like a cathedral

Even before entering, as we approach a medieval city, we would recognise familiar cathedral and other church architecture. These amazing edifices, built as signs of God’s presence, dominated the landscape. In contrast, tall towers of money-making are our dominant city symbols. Perhaps Australian Anglicans are less aware than Europeans of medieval contributions to our Church because so many of our ecclesiastical constructions are so very recent. Few of us grow up, as I did, in a church community worshipping in buildings with unbroken continuity back to the 12th century or beyond. However, St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane is but one beautiful example of this medieval history into which Anglicans across the world are intimately linked. It powerfully expresses continuing medieval gifts: Gothic forms, stained-glass windows, side chapels, choir and music, sacramental emphases, and (after the removal of pews, which is very modern) spaciousness and flexibility for all kinds of gatherings.

St John’s Cathedral’s prominent site, like those of similar medieval-style cathedrals, is also highly symbolic. Humbler churches in smaller settlements were also literally in the middle of their society. For the Church saw itself at the heart of its world and open to all around it. This was certainly linked to its power and desire for dominance. Yet it was also about seeing God in everything and being a source of community and healing for all. In contrast, in later centuries the Church often split into competing Christian factions, each tending to sell its own religious ‘club’ rather than explore the mystery of God in all of Creation.

“St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane is but one beautiful example of this medieval history into which Anglicans across the world are intimately linked. It powerfully expresses continuing medieval gifts: Gothic forms, stained-glass windows, side chapels, choir and music, sacramental emphases”

2. Transcendent thoughts of God

The French philosopher Étienne Gilson (1884-1978) also identified how the great medieval Christian thinkers created ‘cathedrals of the mind’. They brought Scripture together with the best of wider thinking, forming systematic, often beautiful, structures of Christian doctrine. By the 16th century, these had become fossilised and new techniques of reading scripture helped bring Reformations of various kinds. Yet we are impoverished if we view the Middle Ages as backward in faith. Religious dogma was dominant, and superstitions were prevalent. However, there was tremendous discussion. This was, after all, the age of the creation of the great universities of Europe. A broad range of belief and practice also existed at the local level. Significantly, St Thomas the Apostle was popular, as a very human figure who encompassed doubt and other spiritual struggles.

Advertisement

Without the great medieval thinkers, the Anglican Church would certainly be much poorer. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (1093-11O9), is one example. His outstanding work included the so-called ‘ontological proof’ for God and articulating the influential ‘satisfaction’ view of Christ’s atonement. Other key theological ideas emerged from the Middle Ages, notably ‘moral’ or ‘example’ atonement theories, such as those of French scholastic philosopher and theologian Abelard (1079-1142) and the Italian Franciscan Bonaventure (1221-1274), affirming God as loving rather than offended, harsh, or judgemental. Meanwhile the greatest medieval Christian thinker was Italian Dominican Thomas Aquinas, who engaged with sources of ancient wisdom like Aristotle and the brilliant contemporary scholars of medieval Islam, developing highly influential ideas of ‘natural law’, and subtle understandings of the relationship between grace and reason. For despite popular superstitions (of which our own age is hardly free), such medieval theologians can make some later Christian thinking look quite banal.

Window of Thomas Aquinas holding The Summa Theologiae, his best-known work

3. Plentiful pathways of prayer

Medieval Christianity also offered many different prayerful pathways. While, the Church’s hierarchy did seek to impose its authority on all of life including prayer, in practice, however, a vibrant variety of spiritual flowers flourished under the same sacred canopy. Indeed, they were often broader than much that followed. As the Protestant Reformation swept away many less constructive expressions with its stress on the scriptural text, it also narrowed options, particularly for women. Most devastating was the destruction of monasteries and religious orders which had been powerhouses of prayer and welfare. Today physical ruins such as Tintern Abbey in Wales and Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire are still hauntingly beautiful. Particularly from the mid 19th century, Anglicans have thus gradually renewed the best of what was lost at the Reformation. This has included the (re)creation of Anglican religious orders and designated retreat spaces, and life-giving patterns of spirituality.

Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire

Some of the greatest works of Anglican spiritual inheritance are medieval. These include revived traditions such as the Franciscans and designated women’s religious spaces, both highly significant within Anglican development in southern Queensland.

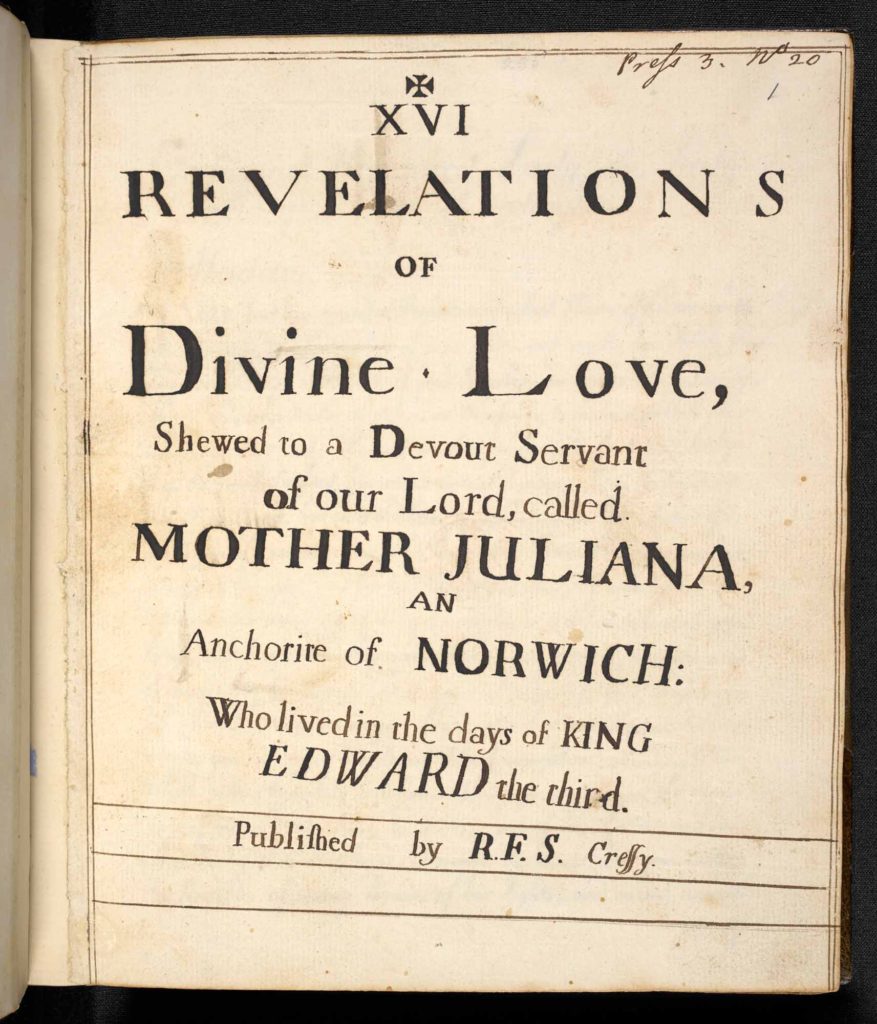

Profound prayer guides include the classic 14th century work The Cloud of Unknowing, written by an anonymous English monk. Women were also prominent, notably English mystic Margery Kempe (1373-1438). Julian of Norwich’s work has been increasingly inspirational recently, helping to renew Anglican contemplative life. Anglicans have also begun to draw deeply again on other neglected medieval spiritual practices, including pilgrimages and labyrinths, rules of life and prayer, art and drama, and ways of developing sensibility to God in Creation.

Recent Julian of Norwich icon by Lu Bro ObJN (Image courtesy of The Julian Centre)

Revelations of Divine Love to Mother Juliana, Anchorite of Norwich: original 1675 manuscript page (Image courtesy of British Library)

Nor did the Middle Ages lack helpful approaches to the Bible. A significant feature, for example, was attention given by great teachers, like French Benedictine abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, to texts such as the Song of Solomon, which later Christians have often overlooked. They articulated vital themes such as the humanity of Jesus, God in the senses, the intimacy of God’s love, and God’s presence in the public and ordinary life of the world.

“Anglicans have also begun to draw deeply again on other neglected medieval spiritual practices, including pilgrimages and labyrinths, rules of life and prayer, art and drama, and ways of developing sensibility to God in Creation” (Pictured: The Rev’d Penny Jones on the labyrinth at St Luke’s Anglican Church, Toowoomba)

4. Anglican order and liberty

To medieval folk, modern privatised faith would make no sense. As symbolised by the centrality of church buildings in the community, politics and economics were inextricably bound up with Christianity. Individualist spirituality, distinct from the community and corporate worship, would also have been incomprehensible. Church and State could consequently be intertwined unhelpfully, and church leaders might be corrupted by power and wealth. The costs of conscientious objection could further extend to exile and death. Yet this brought fruitful engagement with the whole of life. Church leaders, such as Carthusian bishop Hugh of Lincoln, were thus powerful providers and advocates for people who were poor, sick or marginalised (including English Jews).

The story of the martyred Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket’s (c.1118-1170) conflict with King Henry II is the best-known example of medieval struggles for Church liberty. However, it is but part of the medieval shaping of what we now know as Anglican order and freedom. For the Middle Ages, not Henry VIII, established principles of the independence of the Ecclesia Anglicana.

Memorial on the spot of Archbishop Thomas Becket’s martyrdom in Canterbury Cathedral (Licence: ShareAlike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another key figure was the great Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton (c.1150-1228). Dispute involving him was central to the crisis which produced Magna Carta (‘Great Charter’) in 1215, a hugely significant legal definition which included as its first article, directed against both the monarchy and papacy, “that the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired.” Langton is also important to Anglican foundations in other ways. He is, for example, credited with dividing the Bible into the standard modern arrangement of chapters. A distinguished scholar and prolific writer (not least on the Hebrew Scriptures), he also chaired the key English Church Council of 1222, whose decrees, known as the Constitutions of Stephen Langton, are the earliest provincial canons still recognised as binding in English church courts. For much of what was to become Anglican tradition has medieval origins, including the development of English canon law and ecclesial order, as well as key aspects of influential theology, piety, and architecture. Above all, this includes nurture of the English parish and episcopal systems, which have been central to Anglican development to this day.

Window in the parish church of St Giles in Wragby, Lincolnshire where Archbishop Stephen Langton was born (Licence 4.0 International CC BY 4.0)

What fresh value for faith development does the Middle Ages have today?

Recently, many Anglican foundations have been challenged, sometimes radically. These include the sufficiency of the traditional parish system, for we live in a very different age. Yet our times also have quite different dynamics to both Reformation and modern (19th and 20th century) Anglican reformulations. So, in responding to where God is calling us, the Middle Ages may help renewal. The elements briefly explored above offer some directions.

Related Story

Features

Features

The Origins of Anglicanism – what did the Romans, and Celts ever do for us?

Today there are fresh influences which would confine the Church to a privatised chaplaincy role, retreating from the community at large. The examples of Stephen Langton, Thomas Becket and Hugh of Lincoln point us elsewhere. The Anglican tradition is not one of gathered communities, ideologically based and/or exclusive of others. Rather it seeks to stand, metaphorically if not always literally, in the centre, with others, in society. That is the parish’s deepest significance. We can often feel pressured to narrow our identities, being overly self-concerned. In contrast, our medieval forebears support continued openness to the wider world, to what Anglican theologians call true ‘catholicity’.

In being concerned both for our particular faith, and for wider society, the medieval Church also encourages us to learn from others’ wisdom and to wrestle more deeply with our faith, not least contemplatively. We, too, live in an age that often values images over words, participation over received regimentation, diversity over narrow ideas of unity, and which longs for depth and peace in the midst of unprecedented activity and anxiety. In such a world, with its own balance of creativity and contemplative prayer, use of the arts and broad approaches to scripture, medieval spirituality might just have some fruitful pathways to explore.