Julian of Norwich: 'all shall be well'

Features

“Julian’s well-known phrase that ‘all shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well’ comes from a place of great depth that assists us as we, too, face serious global health challenges in the COVID-19 environment,” says The Rev’d Penny Jones on Julian of Norwich, who is marked in our Lectionary on 8 May

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The saint and the sultan

- The man who would be king

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- Anselm of Canterbury

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

- Hildegard of Bingen

I first encountered English mystic, theologian and anchorite Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1417) as a literature student through her line quoted in TS Eliot’s 1942 poem ‘Little Gidding’:

‘Sin is Behovely, but

All shall be well, and

All manner of thing shall be well.’

I was intrigued enough by the footnote to remember the name when, a few years later, I was sent on pastoral placement to Norwich and on a day off sought out her ‘cell’. I found myself embraced by its deep and tender silence. There I bought a small anthology of her writings and was immediately drawn to her emphasis on love, her acknowledgment of the feminine aspect of God and her sheer common sense. She has been a spiritual companion ever since.

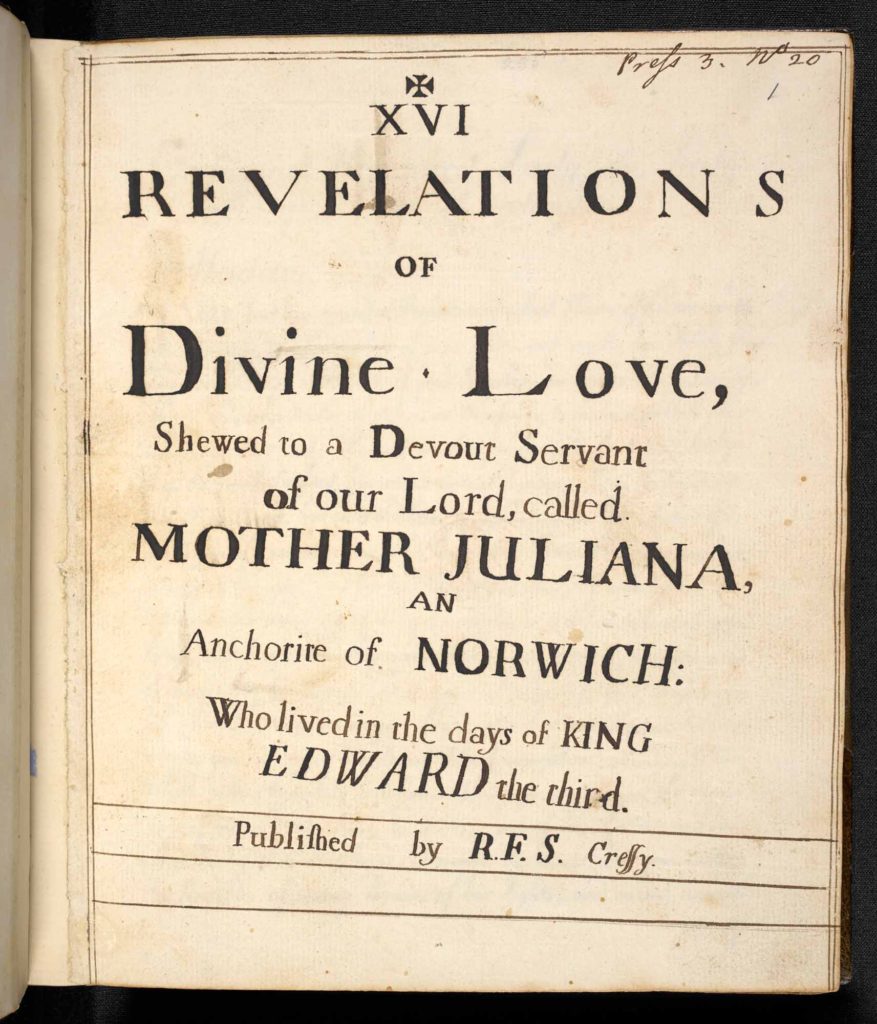

Since the 20th century, Julian of Norwich has become perhaps the best known of all the medieval mystics writing in English. Indeed, her Revelations of Divine Love (or Showings) was the first book to be written in English by a woman. We know very little of her personal life, but her teaching on the contemplative life and her meditation on her experience of God’s love continues to resonate today. In particular, she lived through two periods of plague, in which she nearly lost her own life and experienced the deaths of those close to her. Hence Julian’s well-known phrase that ‘all shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well’ comes from a place of great depth that assists us as we, too, face serious global health challenges in the COVID-19 environment.

Revelations of Divine Love to Mother Juliana, Anchorite of Norwich: original 1675 manuscript title page (Image courtesy of the British Library)

We do not know her real name and must assume that she was known as ‘Julian of Norwich’ because her anchoress’ cell was attached to the Church of St Julian at Corniford in the city of Norwich, where it can still be visited today. Norwich in the Middle Ages was a great centre for trade, especially in wool and textiles, and hence, like ports today, also a great entry point for plague, carried then by rats on boats from continental Europe.

Advertisement

It was not uncommon in the 12th and 13th centuries for women to choose the life of an anchoress. The term comes from the Greek word anachorein, meaning ‘to go apart’ and such people would withdraw from the world entirely in order to contemplate God without disturbance. Such folk certainly understood the value of social isolation! Their ‘cell’ would be attached to a church and would generally have two windows, one opening onto the church so that they could receive the sacraments and the other onto the street, so that they could receive food and water and converse with those who visited them for counsel.

“Her anchoress’ cell was attached to the Church of St Julian at Corniford in the city of Norwich, where it can still be visited today” (Image courtesy of The Julian Centre)

It was a life of withdrawal, but not especially ascetic, and it is likely that Julian had a maid to tend to her needs – it is also thought that she had a cat, presumably to keep the mice at bay! If you are interested in the life of an anchoress, the Australian novelist Robyn Cadwallader has written an excellent book The Anchoress, obtainable from the Roscoe Library as well as from good book stores.

Advertisement

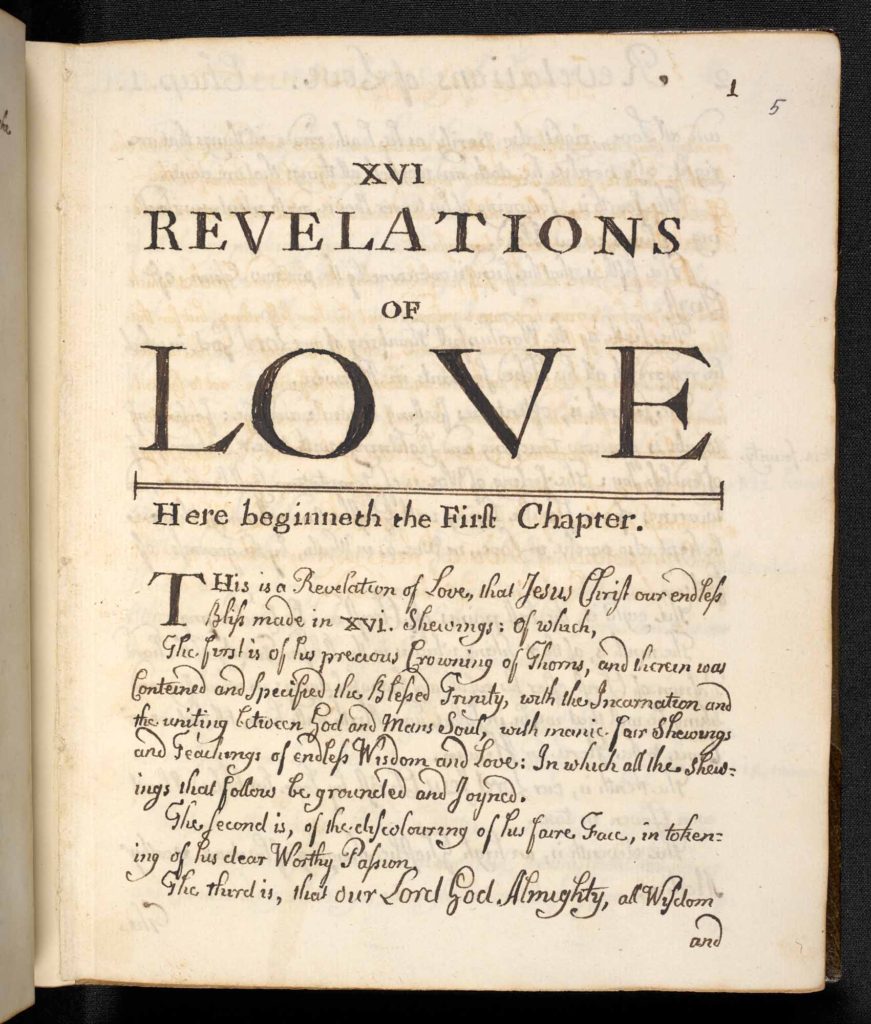

Before she became an anchoress, 30-year-old Julian had a ‘near death’ experience in 1373. She records that the lower half of her body had already died and the upper half was about to do so when she experienced a series of sixteen visions of Christ, after which she recovered. She became an anchoress as a result and recorded her experience in the Shewings or Revelations of Divine Love. This text exists in two versions, the short version of 25 chapters written soon after her experience and a longer, 86-chapter version, which records her 20 years or so of meditation upon her visions.

Julian’s 16 revelations, or showings, reveal her to be a sensitive, sharp and grounded woman, who maintains trust in God’s faithfulness while addressing uncertainty, fear and profound theological themes.

Julian describes herself as an ‘unlettered creature’, perhaps because she does not write in Latin. Certainly, her style is uncluttered and accessible, but she shows a high level of theological acuity, and it has been suggested that she might have received her early education at the nearby Benedictine monastery at Carrow. As a young woman she asked for three gifts from God – contrition for her sins, compassion and longing for God – gifts that might indeed serve us well in this time of uncertainty.

Her visions always return her to God’s love, and this is particularly comforting to us in times of distress. She describes God’s love as ‘so tender that He may never desert us’, and as enfolding and clothing us. She especially reflects on her experience of Christ as Mother, following the teaching of Anselm, whose Canticle on the motherhood of Jesus we find in our Prayer Book on p.428. She writes for example, ‘Our Saviour is our true Mother in whom we are endlessly born and out of whom we shall never come.’

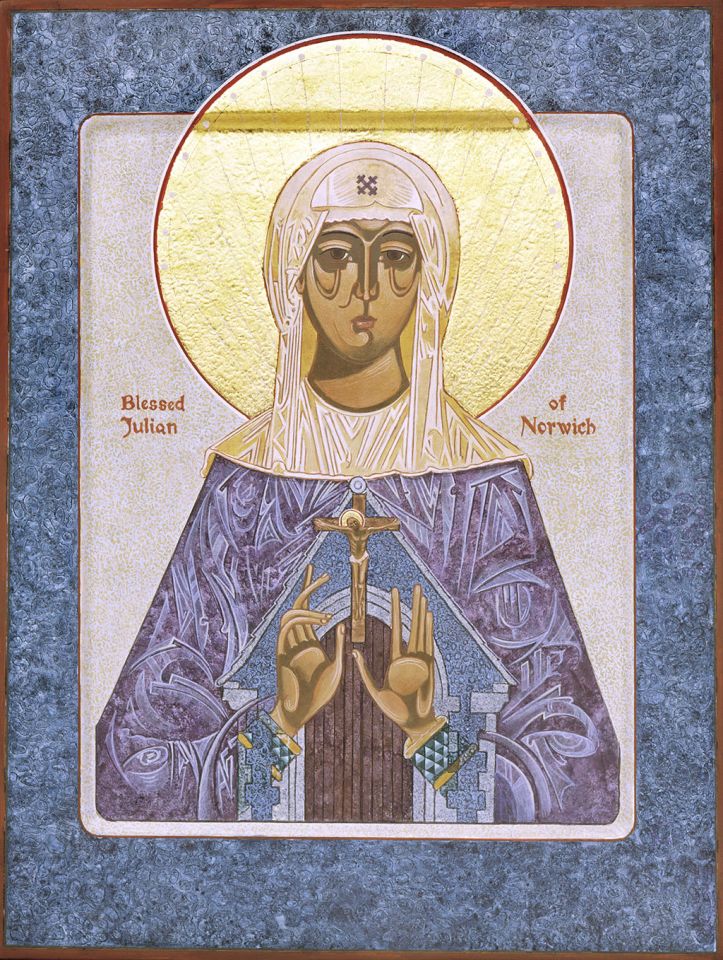

Recent icon of Julian of Norwich by Romanian Orthodox Icon painter, Christinel Paslaru, commissioned by Fr Christopher Wood, Rector of St Julian’s Anglican Church. The icon was used on occasions at St Julian’s, including at a festival in 2014 when Archbishop Rowan Williams carried it through the streets of Norwich (Image courtesy of The Julian Centre)

Julian reflected that ‘God wishes to cure us of two kinds of sickness; impatience and despair’. These are certainly sicknesses of our own times, and as we learn through days of confinement to be more patient and to retain hope, we would do well to turn to her teachings. She writes famously, ‘He said not, “thou shalt not be tempested, thou shalt not be travailed, thou shalt not be dis-eased;” but He said “thou shalt not be overcome.”’ This is a promise to hold close as we journey through these days.

Julian of Norwich is commemorated by Anglicans and Lutherans on 8 May. While not officially a saint, she is popularly referred to as ‘Saint Julian of Norwich’, and remains an inspiration in the modern era. Stained glass featuring her is found, for example, in Mary Sumner House, the London headquarters of the Mothers Union.

“Stained glass featuring her [Julian of Norwich] is found, for example, in Mary Sumner House, the London headquarters of the Mothers Union”

The focus of Julian upon contemplative prayer and longing for God has continued, too, through organisations such as Julian Meetings, which encourage small groups and individuals to gather together for periods of meditative prayer. Often, they begin their time of silence with these words of Julian’s, with which I shall conclude:

‘God of thy goodness, give me Thyself;

For Thou art enough for me,

And I can ask for nothing less

That can be full honour to Thee.

And if I ask for anything that is less,

Ever shall I be in want,

For only in Thee have I all.’

Revelations of Divine Love to Mother Juliana, Anchorite of Norwich: original 1675 manuscript page (Image courtesy of the British Library)

Recent Julian of Norwich icon by Lu Bro ObJN (Image courtesy of The Julian Centre)