St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

Features

“Cuthbert’s profoundest significance lies in his inspiring spirituality, of which three aspects are particularly valuable today. Firstly, his embodiment of key features of Celtic Christianity; secondly, his deep Scriptural grounding; and thirdly, his contemplative prayerfulness,” says The Rev’d Dr Josephine Inkpin on St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne whose Feast Day is celebrated on 20 March

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- The man who would be king

- The saint and the sultan

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

- Hildegard of Bingen

St Cuthbert’s cross hangs in my living room window for very good reason. Cuthbert (634-687) is the greatest of the Northern Saints, pointing not only to vital elements of our English-speaking Christian heritage, but also to powerful central features of our continuing faith. His Feast Day is 20 March, and his life and witness offer us glimpses into a holiness which can enliven our own contemporary world, as it did its own.

“St Cuthbert’s cross hangs in my living room window for very good reason”

Wor Cuddy

In what was the ancient Celtic Christian Kingdom of Northumbria (now northern England and south-east Scotland), Cuthbert is known affectionately as ‘Wor Cuddy’ (or ‘Our Cuddy’), his nickname. This is particularly the case in County Durham, where I was born. For, from early days, Cuthbert was the great spiritual ‘Protector of the North’, not least in that area, between the Rivers Tyne and Tees, known for centuries as ‘the Liberty of Durham’. Today Cuthbert’s cross is still found across the region, including on the County Durham flag. It is a vivid reminder of the close relationship between Cuthbert and his people, the haliwerfolc (‘people of the saint’). Even for many who are not explicitly religious, Cuthbert speaks to the heart and spirit of that people and place, just like Durham’s great Cathedral, built by the Normans in 1093, in which Cuthbert’s tomb has always had a central place. However, his significance transcends his context.

The County Durham Flag, showing St Cuthbert’s cross (courtesy of https://britishcountyflags.com/2013/11/21/county-durham-flag/)

Also known as ‘the Wonder Worker of Britain’, for miraculous happenings attributed to him, Cuthbert lived at the transition between Celtic and Roman Christianity. Indeed, the story goes that, in 651, while working as a shepherd boy on the Northumbrian hills, Cuthbert had a vision of the soul of the great Celtic missionary St Aidan being carried to heaven by angels. This inspired him, at age 17, to become a monk at the monastery of Old Melrose, seeking to be a shepherd for Christ. Thus, in his influential narrative of the origins of the Ecclesia Anglicana, Saint Bede pointed to Cuthbert as both the fulfilment of the Celtic mission and the inaugurator of the reformed Catholic tradition, which he, and we, inherited. For Cuthbert became Prior of Lindisfarne and later Bishop, helping to integrate the wider ‘Roman’ church traditions with those of the Indigenous, or ‘Celtic’, past.

If there is something to be said for Cuthbert, as an abbot and bishop of a transcendent via media (‘middle way’) of his day, Cuthbert’s profoundest significance lies in his inspiring spirituality, of which three aspects are particularly valuable today. Firstly, his embodiment of key features of Celtic Christianity; secondly, his deep Scriptural grounding; and thirdly, his contemplative prayerfulness.

Close-up of St Cuthbert’s statue in the Lindisfarne Priory ruins on Holy Island, Berwick-upon-Tweed, UK

God in Creation and pilgrimage

Among Celtic Christian features that have become attractive today are the rediscovery of God in Creation and the importance of viewing life’s journey as pilgrimage. These are strongly present in Cuthbert. Five centuries before St Francis of Assisi, he was an ancient model of what we might call an ‘eco saint’. The common eider sea birds are known as ‘Cuddy ducks’ in England’s north east, as tradition has it that Cuthbert, an early conservationist, helped save their lives from hunters.

Female ‘Cuddy duck’ nesting

He lived an extremely humble and ascetic life, close to people who were poor and in intimate relationship with the natural world. Indeed, one of the most beautiful Cuthbert stories concerns his connection with other creatures. Late at night, it is said, after his fellow monks had fallen asleep, he would sometimes sneak out of the monastery and head to the sea, to wade into water up to his neck, raise his arms to the sky, and pray with the rhythm of the waves. One night another monk decided to follow him discreetly. He saw Cuthbert wading deep into that cruelly cold North Sea, praying in his customary fashion. He prayed throughout the night, and at dawn returned to the shore and knelt for more prayer. However, when Cuthbert emerged from the sea he was not alone. Two otters followed him, panting on his feet to dry them, and snuggling against his body to warm him with their fur. The otters stayed with Cuthbert as he finished praying, kneeling before him in the sand. They did not depart until he offered them his blessing.

Advertisement

In life, and still more after his death, Cuthbert also called his people to life as a pilgrimage in response to God’s grace. Originally buried in Lindisfarne Priory in 687, his body was later taken by his followers to save it from Viking destruction. Over subsequent years, it journeyed throughout the region as a focus for sanctity, until placed in Durham Cathedral, becoming the primary attraction for visiting pilgrims. In recent years, the rediscovery of pilgrimage as a spiritual tool has led to new developments, such as the creation of the hundred kilometre ‘Cuthbert’s Way’ between Melrose and Lindisfarne.

St Mary’s Church, Lindisfarne: Fenwick Lawson’s statue commemorating the monk’s journey with Cuthbert’s coffin, as they protected his remains from the Vikings

Durham Cathedral has become a primary attraction for visiting pilgrims

Scripture at the heart of holiness

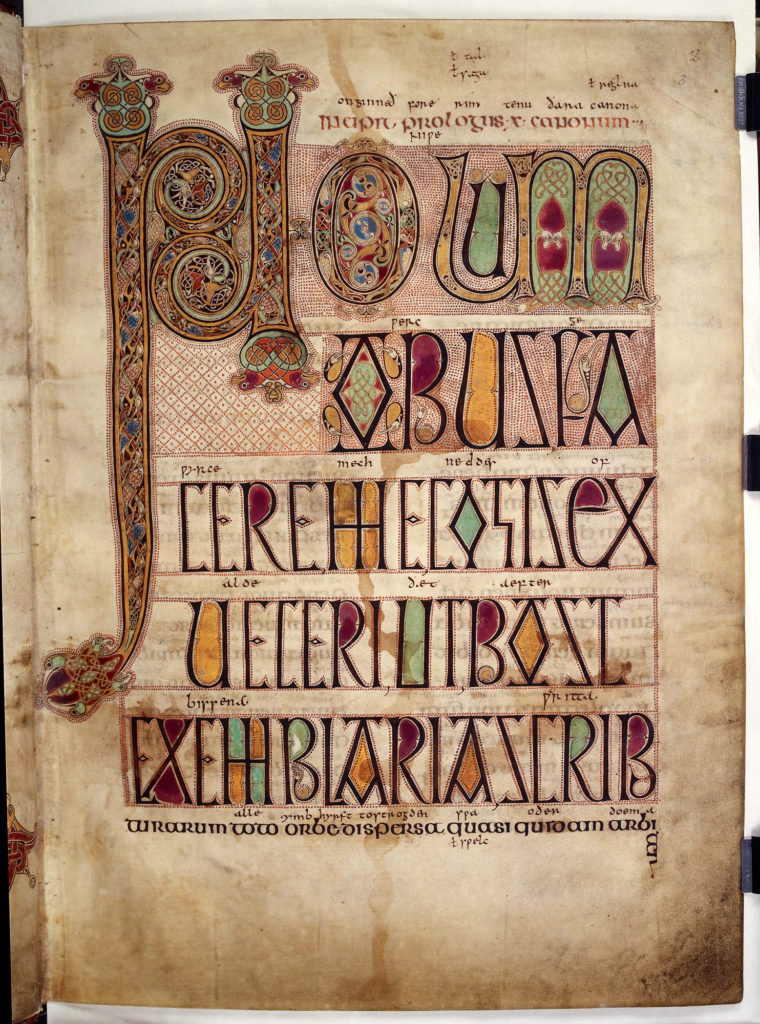

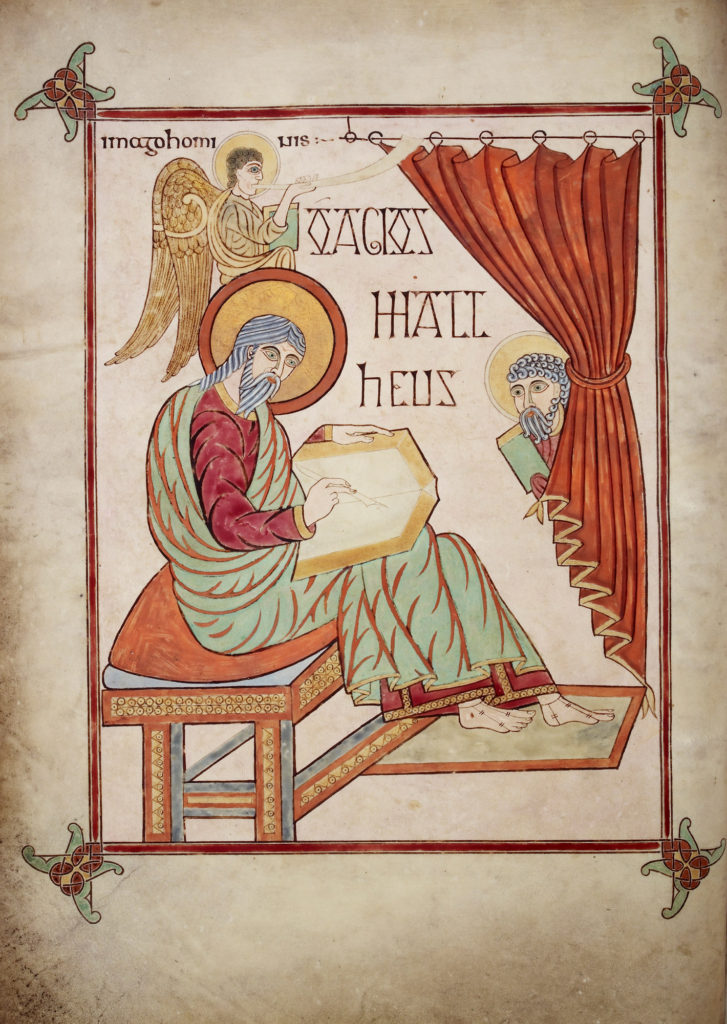

Such spirituality was profoundly grounded in holy Scripture. For Cuthbert was not only immersed daily in the Scriptural reading of the hours, but he shone with the fruits of deep discipleship, not least in his commitment to reconciliation, care for people who were poor and a healing ministry. Thus, the famous Lindisfarne Gospels, an illuminated manuscript made of calfskin vellum, were made in his honour. Indeed, when his tomb was opened, in addition to claims that his body was uncorrupted (an ancient sign of profound holiness), on his breast was found the beautiful Gospel of John – today the oldest complete book of the English Church. It was a profound sign of what truly mattered to Cuthbert.

Page of the Lindisfarne Gospels (curtesy of https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/lindisfarne-gospels)

Page of the Lindisfarne Gospels (curtesy of https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/lindisfarne-gospels)

Living out of deep prayer

At the very centre of Cuthbert’s life was a whole-hearted search for God. He is officially remembered in our Lectionary only as ‘bishop and missionary’. Yet, for all his tireless work for the Church and for people who were living in poverty on the margins, he was above all a hermit and a mystic. At various stages in his life, he thus sought to withdraw into deeper contemplation. At first, he lived alone on the small island adjacent to Lindisfarne, now known as St Cuthbert’s Isle. Then, under pressure from visitors seeking his counsel, he retreated further to the remote Inner Farne island. His greatest gift to us is thus the invitation to nurture our own intimate relationship with God.

St Cuthbert’s Isle

A sign of heaven

As highlighted above, Cuddy/Cuthbert has been many things. Perhaps, however, the following sonnet takes us to the truth: that Cuthbert’s deepest identity lies in him being ‘a sanctuary, a sign, an open door’ to ‘the heart of heaven’. The poem is titled ‘Cuddy’, from the collection The Singing Bowl, published by Canterbury Press, and penned by Malcolm Guite (poet, singer-songwriter, Anglican priest, and chaplain of Girton College, Cambridge):

Related Story

Features

Features

The Origins of Anglicanism – what did the Romans, and Celts ever do for us?

‘Cuthbertus’ says the dark stone up in Durham

Where I have come on pilgrimage to pray.

But not this great cathedral, nor the solemn

Weight of Norman masonry we lay

Upon your bones could hold your soul in prison.

Free as the cuddy ducks they named for you,

Loosed by the lord who died to pay your ransom,

You roam the North just as you used to do;

Always on foot and walking with the poor,

Breaking the bread of angels in your cave,

A sanctuary, a sign, an open door,

You follow Christ through keening wind and wave,

To be and bear with him where all is borne;

The heart of heaven, in your Inner Farne.

St Cuthbert’s grave stone in Durham Cathedral

For beyond all our identities is the mystic universal communion in which Cuddy lived and moved. So, in the spirit of Cuthbert, may the changing winds and waves of his, and my, native land winnow and wash us all with transforming love.

The ruins of Lindisfarne Priory

Lindisfarne Priory ruins from the sea