Hildegard of Bingen

Features

“Hildegard of Bingen is a rare example of someone who touched nearly every field of human endeavour, leaving her mark on all aspects of life. Like Hildegard, we need to take a broader view of the whole of creation – view it and marvel in it,” says scientist and priest, The Rev’d Selina McMahon on Hildegard of Bingen who is commemorated in our lectionary on 17 September

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- The saint and the sultan

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

To me, Hildegard von Bingen (Hildegard of Bingen) was just another nun. I’d heard of her, certainly. She was famous for something or other; probably for founding a religious community. I even remembered that she’d composed music, though I couldn’t honestly say that I knew any of it. Beyond that, I knew nothing of her, until one day in 2018 she appeared in a list of ‘women in science’ while I was consulting for a potential book. Hildegard? A scientist? As I was to discover, she was far more than just a scientist – Hildegard was a renowned theologian, poet, composer, artist, playwright, naturalist, neolgist and medical anthropologist, though she is probably best known as a mystic visionary.

Advertisement

There are many great theologians. Equally, there are many great scientists. But few achieve greatness in both fields. Hildegard was one such person, but she didn’t stop there. After all, there were the arts to consider also. A true polymath, I was to find out that she was a fascinating woman whose interests and expertise touched on and expanded so many fields of human knowledge.

Hildegard was born in Germany in 1098, the tenth child in a reasonably well-off family. From a very early age, she claimed to see visions. These visions appear to have played some part in the decision of her parents to place her in a nearby Benedictine monastery where she was given into the care of a young noblewoman, Jutta of Sponheim (1091-1136) – herself the daughter of a friend of her father. Jutta had rejected marriage in favour of becoming an anchorite, and she accepted Hildegard into her care. As anchorites they were literally walled into their cell for life, meaning that communication with anyone else could only occur through three windows – one into the church to which their ‘cell’ was attached, one to the outside world and one to an adjoining parlour through which food and related waste could be passed.

St Hildegard von Bingen und St Jutta von Sponheim, Kloster Eibingen (Wikimedia Commons licence: Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0)

As time passed, other women came to join Hildegard and Jutta. Additional rooms were built adjoining their cells (though still cut off from the outside world). However, over time, the number of women grew to the point that they ceased to be anchoresses and instead formed a Benedictine convent. Upon Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard was elected as the leader of her community.

Eibingen Abbey near Rüdesheim am Rhein, which was founded by Hildegard in 1165

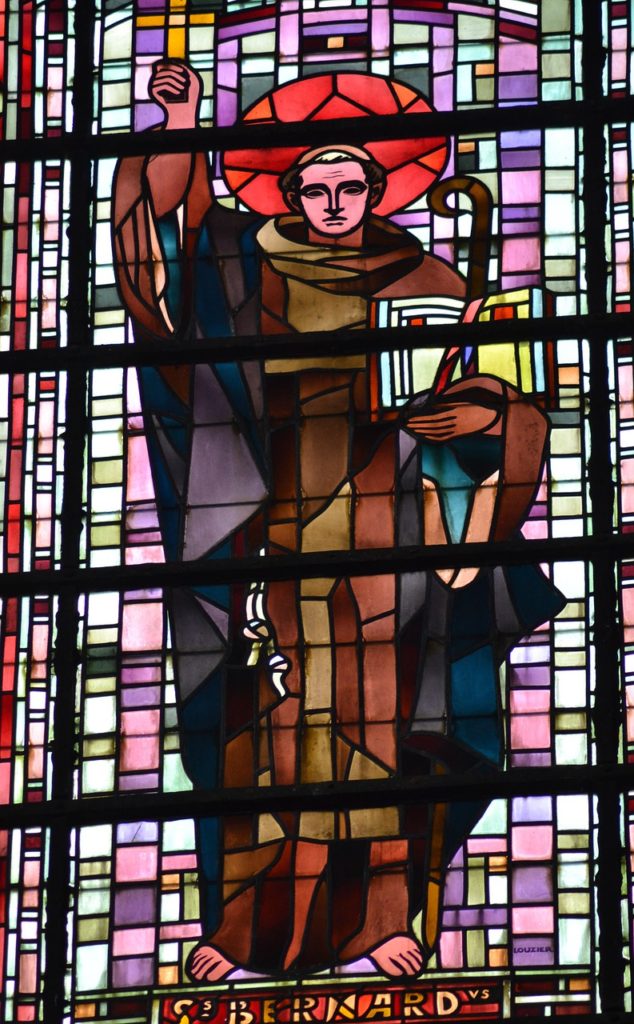

Though the community initially relied on the monks for administrative and financial matters, Hildegard realised that they needed to be autonomous. In order to achieve this, she corresponded with notable men whom she respected, in particular, Bernard of Clairvaux, who was a leading monastic figure in the Benedictine community. By securing his support, along with others, her writings impressed Pope Eugenius III who authorised her to publish her works.

Stained-glass window of St Bernard of Clairvaux

Though Hildegard was reluctant to ever discuss her visions with others, five years later she received a vision that told her to have her visions recorded by the Provost of the convent, who did so and continued to do so for the next 30 years.

Many of her visions were gathered together into a magisterial illustrated work Scivias, short for ‘Scito vias Domini’, or ‘Know the Ways of the Lord’. This was her first major visionary work and contains 26 visions with a theological explanation in each case. Covering such topics as the Trinity, baptism, the Eucharist and even the soul (which Hildegard likened to the sap of a tree, giving vitality and growth to the branches and leaves), Hildegard demonstrated a unique clarity of thought. The final vision, the Play of Virtues (Ordo Virtutum), blended both action and personification and, as such, is commonly regarded as the first morality play. Not content with this, or even the fact that she had invented new words as part of it, Hildegard went a step further and even set it to music.

Hildegard of Bingen created a secret alphabet, Lingua Ignota (Latin for ‘unknown language’)

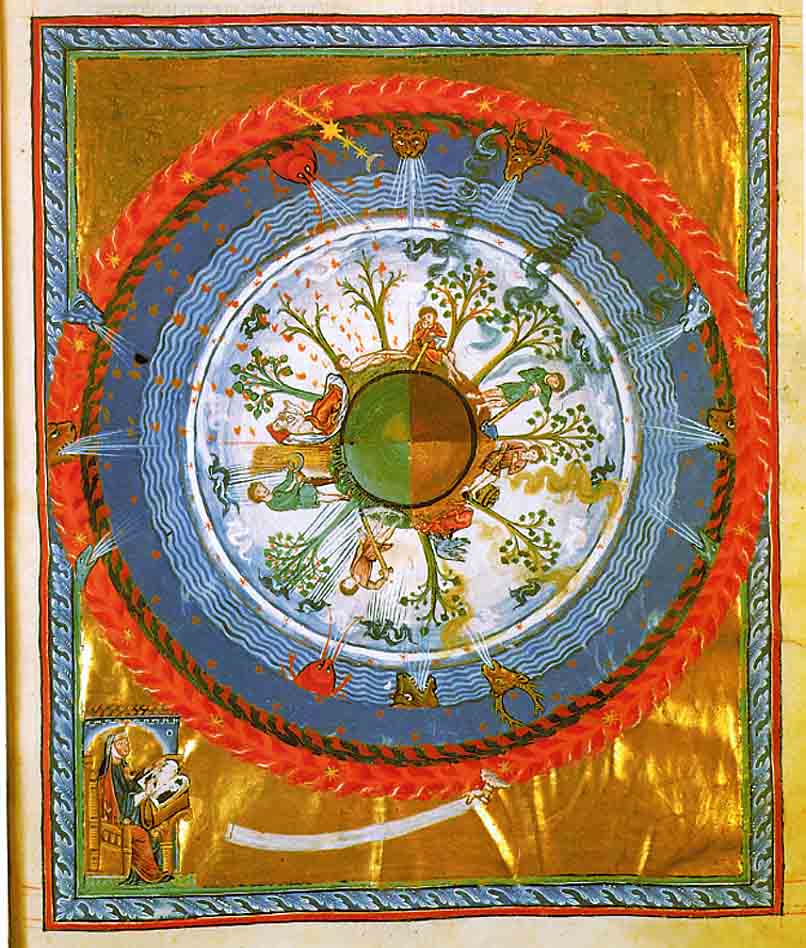

She followed this work with two other collections of visions. The Book of Life’s Merits looks at virtues and their corresponding vices. For example, regarding someone who decides to only help those who help them, Hildegard notes that even gemstones reflect brilliance for others to enjoy whilst gaining nothing themselves. It is mercy that lifts up the broken-hearted and leads them to wholeness. Her third book of visions, The Book of Divine Works is far more cosmological in its spirituality, dealing with the belief that humanity is actually called to co-operate in an active manner with God in the perfection of the creation.

‘Werk Gottes’ by Hildegard von Bingen: Medieval depiction of a spherical earth with different seasons at the same time, from the book Liber Divinorum Operum, or Book of Divine Works (Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Such a body of work would have been sufficient for most people. Whilst she was writing these works, however, Hildegard also wrote Physica which details the healing powers of plants, animals, metals, crystals and so on. Physica is also the earliest known work to feature the use of hops in beer as a preservative. She accompanied this with Causes and Cures, a medical compendium examining the human body along with its illnesses and remedies. These two works did not come from ecstatic visions, but rather from her experience in the monastery’s herb garden and infirmary.

And then there is her music, which can be listened to online. She wrote at least 77 songs – both the words and music. Starting with chants for the nuns to sing the Daily Office, she went on to compose more elaborate songs covering all the seasons of the year. She is regarded as one of the first identifiable composers of Western music (most of her contemporaries go by ‘Anon’).

Fragment of an antiphon: ‘De Spiritu Sancto’ (Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

And her text uses far more poetic imagery than similar music of that time. Take, for example, these lyrics:

Antiphon for Divine Love

Love

Gives herself to all things,

Most excellent in the depths,

And above the stars

Cherishing all:

For the High King

She has given

The kiss of peace.

Hildegard of Bingen is a rare example of someone who touched nearly every field of human endeavour, leaving her mark on all aspects of life. We sometimes get too preoccupied with one facet of living that we forget everything else that is going on around us. Like Hildegard, we need to take a broader view of the whole of creation – view it and marvel in it. God didn’t create a small universe for us to become utterly absorbed in – Creation is far bigger and all of it deserves our attention.

Hildegard von Bingen and her nuns, artist unknown (Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Fiona Bowie & Oliver Davies, 1990. Hildegard of Bingen: Mystical Writings. Crossroad Publishing: New York.