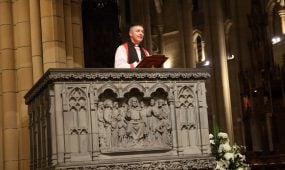

"We cannot surround our love with barbed wire"

Homilies & Addresses

“From Dover in England to Queensland in Australia, the tides rise and fall on innumerable beaches and only the groan of the shingle testifies to the lives lost at sea,” says Archbishop Justin Welby as he speaks about the world’s more than 75 million displaced people in this Washington National Cathedral sermon

Genesis 28.10-17; Psalm 84.1-6; 1 Peter 2.1-5, 9-10; Matthew 21.12-16

Almost forgotten amidst the pandemic, the greatest movement of people in human history continues to grow. In 1945 around 20 million were displaced. In 2015 it was 60 million; today it is in excess of 75 million. From the poorest and most desperate come the cries.

From the burning refugee camp the weeping of the helpless rises into the unhearing air. From the dusty road with the trails of belongings abandoned, children lost, women violated, men humiliated, bodies unburied, there are only the after-marks of horror beyond horror.

From Dover in England to Queensland in Australia, the tides rise and fall on innumerable beaches and only the groan of the shingle testifies to the lives lost at sea.

The causes of movement vary. Poverty, ambition, fear, war all play a large part. Some flee modern slavery. Some run from family or clan disorder. They flee for any and every reason. They may have illusions about their destination and their reasons for fleeing may be more or less understandable. Yet they flee.

The cries also rise from the poorest communities among us. They are the cries of those who find their neighbourhoods changing. For the refugees do not normally come to the wealthy areas but to the poorest.

As they always have since the USA was founded, since the pilgrims 400 years ago, since the words of Emma Lazarus’ sonnet on Lady Liberty were inscribed, “Give me your tired, your poor,/ Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”.

Advertisement

These are the words that have made the USA admired across the world. Yet when they came they too often had to continue to yearn. They came to poor areas and, as in London’s East End in the

19th century and many parts of the UK today, they brought change.

Those already there often say “we are not cruel, not antagonistic but you in the richest parts of the land, recognise that taking so many strangers in and sharing the inadequate resources we have…why, that is almost impossible.”

Like the travellers, the voyagers, they are often not heard until they vote; until their voices are channelled so loudly that they can no longer be ignored.

We do not as Christians resolve problems by their over-simplification, that is the broad road with much good company of those who we can find who will agree with whatever view each of us chooses.

The path of the cross, of following the Crucified God in His journey, is one that tells us to embrace the complexity of suffering and walk alongside those with whom we disagree passionately, bearing our crosses. That is even more true in the time of pandemic, where fear is as prevalent as the virus and causes us to turn inwards.

Advertisement

The readings of this day confront us with complexity, for they are about movement, refugees and home.

We began with a lonely victim of self-imposed family trauma. Here is a narcissistic conman, found out, thrown out, down and out. He has cheated his father and his brother.

Yet God’s grace and love are greater than his sins and failing. He is in great danger. Hot pursuit is close behind him. Wild animals are round about him. Yet God, the unknown God of his ancestors, is with him.

In Jacob’s ignorance and sin God draws near, rescues, blesses and sets him on a new course. His future is of blessing received and giving.

Here is no simple solution. Virtue is not rewarded, nor sin punished. There is no comfortable sense that because he is blessed he was therefore right. God’s grace is lavish and also demands all that we are.

Before Jacob, as well as blessing, are 14 years of gruelling and underpaid labour. He will live by his wits, cheat again. Yet God’s grace remains lavish.

Politics is the art of enabling good and flourishing communities: its materials are the bent and twisted forms of human beings like Jacob. His complexity of action and motivation is met in God not by simplifying or condemning but by calling. He is to be faithful and obedient.

When we see the refugee and those who fear them we must not compromise with false simplicities: but we do channel the abundant grace of God.

Our second reading, 1 Peter 2, tells us that the largest nation on earth is not China or India; the most powerful is not the USA. The greatest nation is without borders, without an army, without passports on paper. It the nation of God’s people – all those who having been aliens and strangers are now transformed into being God’s own people.

Aliens and strangers in Peter’s world were like the undocumented today. No matter how rich, they had little or no protection in law, nor any remedies from the courts. They existed in large numbers because every city and province had its own residents and its aliens.

Peter tells the churches that they have been changed and they now exist as God’s unique people, called to be holy and separate from sin – not a point to overlook. They must reflect the nature of God. Faithful, full of grace, loving one another and even their enemies. Committed to peace. Resilient in time of trouble, as we also must be now.

Their resilience, faith, grace have a purpose. They have a message to proclaim: God who is in the transformation business is liberating people from darkness into God’s wonderful light.

Because they – we – were aliens and strangers, we know that God loves the Jacobs. Because we were exiles, we love exiles.

How that must change us! We cannot hate what we choose or surround our love with barbed wire so that only those with the password can be its recipients. We are God’s people. It is God who chooses, not us.

God’s country is not a democracy; it is an autocracy of the purest love, the greatest purity. We do not choose to be its citizens, its ruler called us out of helpless darkness. Our role is to proclaim; our joy is to celebrate.

That is not always how we show ourselves. Treating church life as politics and our way of doing things as superior, we engage in malicious comment through social media, we are insincere, we are cruel.

We have been transformed by the grace of God alone, yet we behave as though we then had to wage a civil war in God’s church so that our views may prevail. It is no wonder that in the Global North we see numbers decline for the rule of love has become the rule of self.

As Peter says, realistically, “rid yourselves” of such things. Being human and thus failing to be all that we should be, all that we will be, is not new.

In the gospel we see the nature of home. For our home is not a building, not even one of the splendour of the National Cathedral. Home is the people of God built together as living stones by the master builder of all creation.

Jesus in the gospel passage draws all our attention. He casts out the money changers and merchants – we all remember that. We forget that he brought in the children, the blind and lame. The former praised God, the latter found healing.

How dare He! Unqualified to praise in good theology. Disqualified to be in the temple by their injuries and bodily incapacity, both groups were the antithesis of those he cast out.

Yet he calls them in, showing the reversal of everything that is the reality of the Kingdom of God.

The Kingdom of God is not the church: the church points to the Kingdom.

The Kingdom is seen in those caring for the outcast and the marginalised.

The Kingdom is seen in the foodbank where, to quote someone in Dover near Canterbury, “I came seeking food and went with a parcel of love”. They had come ashamed, they went restored.

The Kingdom is seen where people act for others. The Kingdom is to be seen and proclaimed.

In this great cathedral, in a side chapel, is a Coventry Cross of Nails. It has been there for very many years. It is the symbol of the worldwide community of the Cross of Nails based around Coventry Cathedral. Nails that symbolise the horror of war – taken as they were from the bombarded ruins of the mediaeval Cathedral – and the strength of resurrection love, sent by the community that rose from the ashes and ruins.

In 1940 the Provost of Coventry saw a vision of the Kingdom of reconciliation and those crosses, in churches all around the world, point to forgiveness, reconciliation and hope. In your own nation will you live that out? Will your symbols be your proclamation? Especially in these times where injustice is faced, judgements made and hopes flare or fail, depending on your side, your background, your race. Especially in this time of COVID-19.

In the psalm we heard of the beauty of home, that even the sparrow has a nest and the swallow a home.

St Benedict in his Rule speaks of stability. For it is stability that is the sign of home. Stability that is built on fear and exclusion is a fake. Stability is to be in the dwelling place of God and we know, we dream, we long, we pray that the place of stability may be the living, love embedded, grace abounding church of Christ in its myriad forms.

That it may be the church that, knowing its exile, loves the stranger, knowing its grace received loves the enemy, the poor, the weak; knowing its forgiveness, has become the home of a forgiving Spirit.

May you and I join in that place of travelling that makes the valley of Baca a spring, and be of that company that goes from strength to strength: the people of God.

First published on the Archbishop of Canterbury’s website on 27 September 2020.