The Grace of Grice

Homilies & Addresses

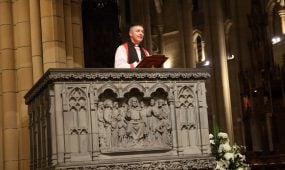

By popular request, anglican focus has published this equally poignant and humorous homily that was given by our Archbishop at the consecration of Peter Grice as Bishop of Rockhampton on Wednesday night

Consecration of Peter Grice as Bishop in the Church of God

St Matthias’ Day

24 February 2021

St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane

Acts 1.14-17, 20-26

Psalm 84

Phil 3.13-21

John 15.9-17

Peter stood up among the believers who prayed, “Lord … show us which one you have chosen” (Acts 1. 15, 24).

Since 22 February 2020, just over twelve months ago, the people of Rockhampton have prayed that same prayer.

The idea of being chosen is strongly emphasised in tonight’s Gospel: “You did not choose me, but I chose you,” says Jesus.

That emphasis echoes throughout this consecration rite. The provincial registrar will certify that Peter Grice has been duly elected according to the Constitution and Canons of the Diocese of Rockhampton, and that the Diocesan bishops of the Province of Queensland have confirmed Peter’s fitness for this office. All present will be invited to declare that the people of God accept Peter to minister as a bishop in the Church. These are all aspects of God choosing Peter through the Church.

Peter, in years to come if you ever question “Why me?”, if you ever get frustrated or disappointed or exasperated at the shenanigans within your own Diocese, or in the national Church, or in Australian society and bemoan the lot that has befallen you, and ask “Why me?”, the answer is on the lips of the Lord: “You did not choose me, but I chose you.”

That fact is made an objective historical reality in this episcopal ordination rite. A long journey of maturing in ministry, of discernment, of prayer, culminates tonight. Throughout your ministry you will be able to look back on tonight and say, “It happened. It happened on St Matthias’ day 2021 in St John’s Cathedral, Brisbane: I was chosen and appointed by Christ through Christ’s Church to this office and ministry of bishop in the Church of God.”

Advertisement

But here’s a conundrum:

There’s a thing in theology called ‘the scandal of particularity’. It’s expressed in the aphorism: “How odd of God to choose the Jews.”

It’s no less odd, it seems to me, than that God should choose Peter Grice to be Bishop of Rockhampton. Out of all the options open to God, why Peter? I doubt very much that Peter would say: because of his superior holiness or intellect or knowledge of the scriptures or pastoral acumen or organisational ability. Why then?

And adding complexity to the conundrum: why would God choose Peter to be Bishop of Rockhampton and me to be Archbishop of Brisbane at the same time?

This is sensitive, perhaps even dangerous, territory and I should be careful not to make unwarranted and unfounded assumptions. But external observers looking on the Province of Queensland might conclude that Peter and I are a bit of an odd partnership with different backgrounds and outlooks, different convictions and priorities. Observers might anticipate that we will disagree, even clash; that conflict, struggle and fireworks are in the wind. How odd of God to choose both Peter and me.

Advertisement

As I say, be careful. This is mere speculation and may prove to be groundless in reality. But I have no doubt that those perceptions are out there.

Such perceptions seem to me to jump the gun. Tonight is the first time Peter and I have met in person. At the time of his election I spoke with him on the telephone. But since then all the arrangements have been made by intermediaries liaising for us. So we are yet to get to know each other personally.

Despite that I have reason to hope.

It has long been my practice to invite a candidate for episcopal ordination to choose whom they want to lead their ordination retreat and to preach at their consecration. As usual I extended that invitation to Peter.

I was somewhat taken aback by his response.

It says more about me than it does about Peter that I expected Peter to choose a firm evangelical, even a conservative evangelical, to preach on this unique occasion. But to my surprise the message relayed back to me from Peter was “I would like my Archbishop to take on that particular duty.”

As I say, I was surprised, if not shocked, by Peter’s response.

It’s not news to anyone that conflict looms large at present in the Anglican Church of Australia. Cultural, theological and exegetical wars are well advanced and unrelenting. Temperatures run high. Relationships are frayed to breaking point. Tempers are strained.

Various groups, firmly convinced of their own unassailable grasp of the truth, use every opportunity to press their own convictions through all available media and, it seems, refuse to acknowledge any truth whatsoever in the convictions of those they see as ‘opponents’. Political machinations are rough.

In this context, Peter’s response was profoundly gracious.

It has had, and may well continue to have, ramifications beyond what even Peter himself might have intended.

That’s what happens with grace!

At a purely personal level, Peter’s graciousness opened my eyes to the extent to which the current unholy context in the Anglican Church of Australia had eroded my own sense of faith and hope. Peter’s response pulled me up short. It was, for me, a moment of recognising how far I had fallen short, a moment of repentance, if you like, an experience of healing, redemption.

It won’t escape you that this instance of repentance was not evoked by judgementalism, brow-beating and finger-wagging. Repentance and redemption were evoked by the shock of graciousness.

That’s what grace does.

Beyond the purely personal level of human relationships, though, I was taken aback, too, by Peter’s respect for the office of Archbishop, for this office in the Church. To one of our intermediaries Peter described himself as a ‘protocol man’, but there is much more than protocol at stake in his decision. It may well have extensive ramifications institutionally and, more deeply, ecclesiologically.

In a recently published book, Melbourne Anglican priest and scholar, Alexander Ross, argues that we might well find a way through the current woes of the international Anglican Communion by reclaiming the ancient place of the autonomy of the ecclesiastical province and of Metropolitical authority, as long as both are properly understood.

Ross (2020, p.22) argues that as early as the Council of Nicaea in 325, and the Council of Antioch, some 15 years later, the ancient Church was well used to the role of the province and the relationships between diocesan bishops and their metropolitan. This is all set out quite explicitly in the Canons of those Councils.

They emphasise proper subsidiarity: a bishop makes decisions regarding his (and we would add or ‘her’) own diocese, but introduces nothing significantly novel without the assent of the metropolitan.

And the metropolitan’s authority is not at all absolute. It’s “balanced by… a consensual collegiality with the other bishops” (Ross, 2020, p.23).

When there’s disagreement among the bishops in a province the metropolitan is responsible to consult neighbouring provinces.

Alex Ross argues that the relational approach envisaged by this provincial polity and metropolitical authority is a much needed corrective to what he regards as the poverty of ‘national church’ polity. The idea of the national church was adopted in England at the time of the Reformation, for non-theological political purposes, and uncritically exported and adopted elsewhere as the British empire expanded. In his view it is a plague on the Anglican Communion, exacerbated by national churches personified in Primates illegitimately arrogating authority to themselves.

Much is to be gained by reclaiming the ancient customs of provincial polity and properly understood metropolitical authority.

I’m not suggesting Peter had all this in mind when he described himself as a ‘protocol man’ but, in the providence of God, Peter may have stumbled across a goldmine of ecclesial possibilities unmined for centuries.

That’s the kind of thing grace does! It transforms in unexpected ways – at the personal level, yes, certainly, but also at the institutional and ecclesial levels. We’ve been a bit short of grace in recent times, I think.

Most profound of all, of course, Peter’s graciousness eloquently manifests and expresses the very heart of the gospel. It resonates with the nuances of tonight’s passage from John.

“This is my commandment, that you love one another. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends…You did not choose me but I chose you. And I appointed you to go and bear fruit, fruit that will last…I am giving you these commands so that you may love one another.”

It‘s been observed (Askew, 2015, p.176) that love in this passage is not an internal subjective feeling or a psychological state. It’s “an action- a really difficult action”. It’s a radical willingness to die – and not, notice, for someone incredibly close and dear to you – “your child or your spouse” – but for a fellow member of the Church! We struggle even to be civil and courteous to fellow Church members. How many of us ever contemplate dying for such a one?

Yet this goes to the heart of who Christ is and reveals the Father who sent him. It’s the kenotic heart of the gospel of the Christ who empties himself, humbles himself, exposes himself to exploitation and even ridicule and harm from others in manifesting graciousness.

This love is not sentimentality or warm feelings, but a profoundly costly action that “creates, redeems, bears fruit” as the one who loves lessens him/herself and lays down their life for others (Askew, 2015, p.178).

This love, God’s love is “generative…[it] creates something new, [it] restores what has been broken, completes what’s unfinished, heals what has been hurt” and the lover diminishes him/herself in order to bear this fruit (Askew, 2015, p.180).

Peter’s gracious response to my invitation points to the heart of the gospel and to a way forward for the Anglican Church of Australia:

“As tensions rise within the community of faith it is Christ-mindedness rather than like-mindedness that will enable us to show compassion to our friends in the faith and to keep the peace from being shattered.” (Askew, 2015, p.179)

Christ-mindedness is a radical willingness to diminish oneself in graciousness to others: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. And that is to abide in Christ’s love, who abides in the Father’s love. It is to be one with the Father, in Christ.

So, Peter, your vocation as bishop is pretty straightforward. Let me sum it up for you:

- You “will give every priest the parish he [or she] wants, and every parish the priest it wants” without allowing long interregna.

- You are to be “a pastorally sensitive, administrative genius,” turning around complex correspondence within two days while always having your door open to whoever might drop by.

- Without fear or favour you are to “preach the Gospel prophetically in a non-threatening way” as you welcome and affirm everyone.

- You are to reverse the decline in church attendance without appearing triumphalist or being overly concerned about numbers, engaging hordes of young people in an atmosphere that provides comfort to the elderly.

- You are to be a strong, decisive, innovative leader who exploits opportunities in a timely way while always acting collegially, consulting extensively, keeping everyone happy and never departing from received orthodoxy.

- You will always be out and about around the Diocese spending time with clergy and laity alike as you remain up to date with theological and biblical scholarship and international affairs.

- You will fearlessly defend the rights of the poor, weak and vulnerable in the community while avoiding dabbling in politics.

- You will be a holy person, immersed in prayer and meditation while keeping a weather eye on the real world of budgets and finance.

- You “will provide extensive social services and educational programmes at low cost, with few bureaucrats.”

- You will give clear strategic and policy direction in a non-directive way while being a good listener and not selling out theology to managerialism.

- You will be unshakeably loyal to your Archbishop while being your own person and refusing to be pushed around by him.

- You will do all this with a smile on your face which doesn’t undermine your natural gravitas, being out and about your vast Diocese seven days a week and while being an exemplary husband and father and being constantly attentive to your family.

(Adapted from source quoted by Donald Cameron, St John’s Cathedral Brisbane, 2 February 2003).

That much is perfectly clear and straightforward.

Never forget though, that your ultimate responsibility, which is a bit trickier, and set out in the gospel reading for this Feast of Matthias: that is to prevent, as far as within you lies, a failure of love among the people of God within and beyond the Diocese of Rockhampton.

You have been chosen and appointed to bear this fruit, fruit that will last.

The truth is that despite our differences we are one in Christ and we are to love one another as Christ loves us. Your task is to manifest that truth.

How will the world believe that God has reconciled all things to himself in Christ if we give up on it?

Amen.

Askew, Emily. 2015. John 15.12-17. ‘Theological Perspective’, pp.176-180, in Jarvis, Cynthia A. and E. Elizabeth Johnson (Eds). Feasting on the Gospels – John, Volume 2, Chapters 10-21. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Ross, Alexander. 2020. A still more excellent way. Authority and polity in the Anglican Communion. London: SCM Press.