Six medicos, six takes on 2019's World Health Day theme

Features

This year’s World Health Day theme is ‘Universal health coverage: everyone, everywhere’ – six local Anglican medicos share their experiences providing health care locally and internationally, in challenging and rewarding circumstances

Sunday 7 April marks World Health Day, a World Health Organisation (WHO) designated day, which WHO promotes to campaign for its number one goal of achieving universal health coverage. The key to achieving this goal is ensuring that everyone can obtain the care they need, when they need it – right in the heart of the community. Progress is being made in countries in all regions of the world. Six diverse local Anglican medicos share how they have contributed to this goal and the lessons they have learnt along the way.

Birthing on Country – Josie Greaves, Registered Midwife, Registered Nurse and Lactation Consultant

I am a non-Indigenous midwife providing continuity of care for and with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women, babies and families. ‘Birthing on Country’ is a culturally sensitive model of care that the team I work with is aiming to provide to the Sunshine Coast Community.

“ ‘Birthing on Country’ is described as a metaphor for the best start in life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies and their families.” (CATSINaM, Australian College of Midwives, Crana Plus, 2016)

Continuity of midwifery care means that as a midwife I meet women as early as possible in their pregnancy once they have been referred for care to the hospital I work for. I continue to be their midwife throughout their pregnancy, often coordinating appointments with other health professionals within our team as required, preparing the women and their families for birth, being available (on-call) for them when they go into labour and continuing with midwifery support for two to three weeks after the baby is born. My role includes collaborating with community organisations and developing and nurturing relationships with community Elders, as well as ensuring the women and their babies are getting access to health care in a manner that is culturally sensitive and supportive.

Advertisement

It is recognised that the vast majority of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women living in rural, regional or urban settings are no longer birthing on ancestral lands, despite the cultural and spiritual importance to do so. The ‘Birthing on Country’ models of care aim to work for and with the women and their families to provide care that supports mothers, strengthens families and nurtures communities.

Midwifery, for me, is a vocation. It’s not just a job. I offer my skills, support and counsel to women to help them be the best mothers they can be, to feel strong and in control of the choices they make as they navigate a health system that is often impersonal, overwhelming and sometimes threatening. For Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women, the health system can be intimidating and it is not always recognised as a place of healing or safety. The most important part of my job is building a relationship with a woman and her family so they can access health care where they feel, and ARE, safe at one of the most significant moments of their lives.

(L-R) Midwives Josie Greaves, Natasha Sau, Jacqui Dulieu and Karen Seville at an opening event of a local Aboriginal-run community program

Do rough sleepers have equal access to universal health care? – The Rev’d Dr Ann Solari, Deacon at St John’s Cathedral Brisbane and General Medical Practitioner

We live in a country where the public health care coverage is amazing. Nearly everyone can access a bulk billing GP and nearly everyone can access top-class treatment in our public hospitals, particularly when very sick or needing emergency treatment.

But for many of the disadvantaged persons I talk to daily, utilising that care effectively can be challenging when you sleep rough.

Advertisement

How does the hospital contact you nine months after your referral was made when you don’t have a permanent address and you changed your phone number so your ex-partner couldn’t contact you, or because your phone keeps getting stolen or lost, or because you can no longer afford to pay for the phone?

How do you get to and from your appointments when the system decides that they will see you in Redcliffe instead of Bowen Hills and you have no money until next Tuesday?

How do you take your medication regularly when it needs to be kept in a fridge and you don’t even have a front door, or your medication keeps getting stolen, or you can’t remember when you last took it?

How do you wait for three hours to be seen, when if you miss your appointment with your job network provider, your Centrelink payments will be stopped?

How do you admit to your health care provider that you cannot afford to buy the medication they have prescribed, get the treatment they have recommended and see the specialist they have referred you to?

How do you do what you are meant to do when you cannot read the instructions?

These are some of the quandaries I face with my patients daily in my work as a GP.

As followers of Christ, we are challenged to make a preferential option for the poor, namely, to create conditions for marginalised voices to be heard, to defend the defenceless, and to assess lifestyles, policies and social institutions in terms of their impact on the poor.

How do we, as Christians, help make sure that people who are poor, or homeless or marginalised are able to access the health care that they are entitled to?

The Rev’d Dr Ann Solari with her GP gear outside St Martin’s House, Ann St

Universal health coverage matters to God – Dr David Lean, Paediatrician and St Bart’s, Toowoomba parishioner

Why should World Health Day’s focus on universal health coverage matter to you? In short – because it matters to God. Because God cares about the broken, the sick and the lonely.

Just a few kilometres separate the northernmost Australian islands in the Torres Strait from the Papua New Guinea (PNG) mainland. Papua New Guineans struggle with some of the most significant health needs in the world – yet are so often forgotten by their nearest neighbours. Surely when Jesus commanded his followers to love their neighbours as themselves, he had the people of PNG in mind.

For many in PNG, access to health care is often impossible. Rugged terrain and a developing world economy are a poor combination for any health care, let alone good health care. It’s perhaps then not surprising that PNG has such substantial health needs. About one in every 20 women in PNG will die as a result of pregnancy complications. A similar ratio of children will not live to reach five years of age. PNG was declared polio-free in 2000, but in 2018 this dreaded disease re-emerged.

Yet, as important as healthcare is – the ultimate needs of the people of PNG, are the same as the needs of the people of Queensland. God’s diagnosis for us all is our sinful state before Him. In God’s eyes, there is no difference between a 16-year-old girl from the Hewa tribe in remote PNG and a 65-year-old farmer from Chinchilla. He made us equal. Our sin is equal. He loves us equally, and he showed this by sending Jesus – to live, die and rise again – for us!

For those of us privileged to serve in healthcare professions, we ought to provide the best care we possibly can. We ought to be knowledgeable, safe, caring and servant-hearted. Yet, as we serve our neighbours and strive to meet their needs – whether in Australia, PNG or anywhere else – it is vital that we do not forget that even the very best healthcare provides just a temporary reprieve. At some stage or another, we all share the same destiny on this earth – death. Thankfully though, we worship a life-giving God. We must show Christ in our actions, and as able – tell the Good News of what He has done. Only this medicine can truly save.

David and Mary Lean outside Kudjip Church with sons Hudson, Zeke, Toby and Judah during their 2017 visit to Kudjip Nazarene Hospital in the PNG Highlands with Samaritan’s Purse

How rejection led to a turning point – The Rev’d Dr Graham Warren, medical doctor and Priest-in-Charge of St Paul’s, Roma

The importance of universal health coverage is a theme that has recurred throughout my life in medicine. In 1994 when the civil war in Bosnia was raging, I thought to volunteer for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), also known as Doctors Without Borders. My application to volunteer for MSF was rejected on the grounds that I had no experience working in the Third World. “How can I volunteer in the Third World if a precondition for this is past experience?” I asked. We have a Third World, in fact a Fourth World in terms of health, right on our doorstep in Central Australia I was told. So, my wife, Imelda, and I decided to work for an Aboriginal Medical Centre in South Australia, and this became a turning point in my worldview.

I learned many things in this role. I learned that health care is anything but universal, even in this ‘lucky country’. I met patients who would walk for four days to see a doctor. I met patients for whom English was a fourth language. I met diseases I thought only remained extant in Africa. I met myself in a new way.

Reflection upon this gave me a sense of greater commitment to sharing the Christian imperative that drives me. The journey to ordained life began with this. It was not a radical disjunct from my life in medicine. In fact, it was a seamless transition.

I find it constraining that we are sometimes so preoccupied with our internally obsessed focus on pew attendance. God is alive and active in the world and we are called to get out, join in and inject our perspective into the mix. It is not falling church attendance that I bemoan. I bemoan the diminishing Christian influence on our contemporary culture.

It is foolish to despair because our most precious gift to the world at this time in history is hope. Hope based not upon wishful thinking, but hope that is the core of our being. Why? Because we are universally connected as spiritual beings; each enjoying a short but beautiful bodily experience. We belong as salt to the world. We are called to serve as our talents and circumstances permit openly and enthusiastically in the common conversation that is happening in the public square.

On this World Health Day our contribution is to offer hope and encouragement to all as spiritual food for the journey.

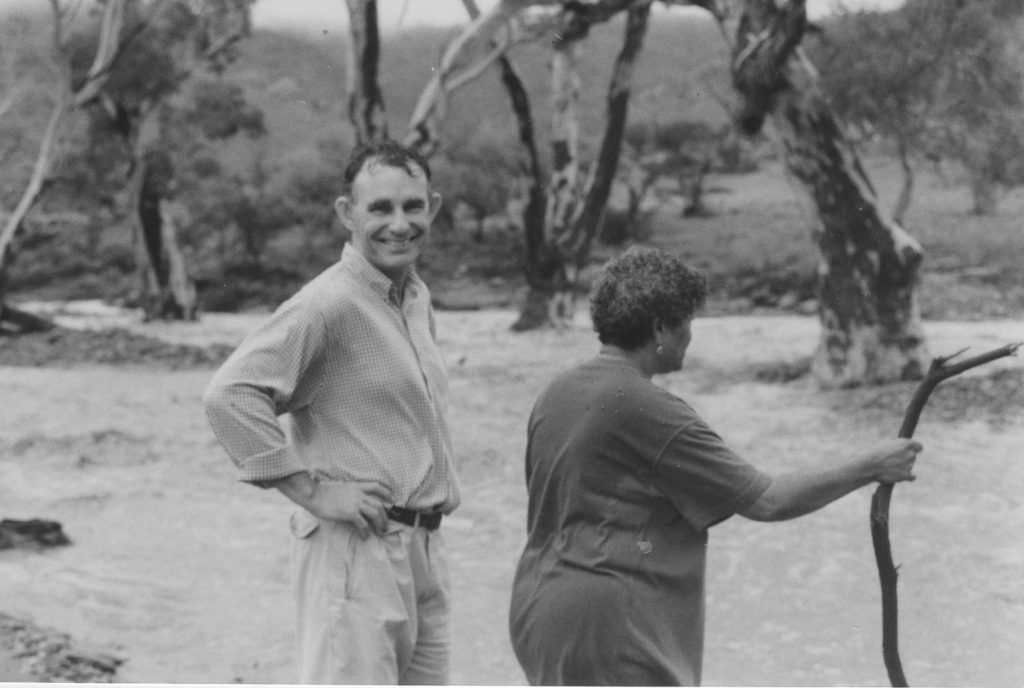

The Rev’d Dr Graham Warren on route to one of his clinics at Neppabunna in the northern Flinders Ranges, South Australia in 1997

Lessons in resilience and humility – The Rev’d Dr Imelda O’Loughlin, medical doctor and Assistant Priest of St Paul’s, Roma

I practised medicine for about 40 years before entering the priesthood. With World Health Day approaching, I look back to those years, which were spent mainly working in women’s health in Aboriginal communities and in diagnostic breast clinics and cosmetic medicine. The thing I remember most clearly about this time in my life is the resilience of women. That resilience seemed to grow out of relationships. Our mothers, grandmothers, daughters, partners, friends, sisters and lovers strengthen our lives by their very presence.

Resilience is found, too, in humour. I worked for an Aboriginal Health Service in Port Augusta at one time. I remember when my contract there ended, my thoughts readily went to how much I had laughed with my patients and co-workers and how I would miss that. Despite the palpable sense of deep unresolved grief reaching across the generations of our First Nations, the people themselves loved and trusted and laughed. There are so many stories that I could share of generous humour and a preparedness to laugh with me when I inadvertently made yet another of my many cross-cultural faux pas.

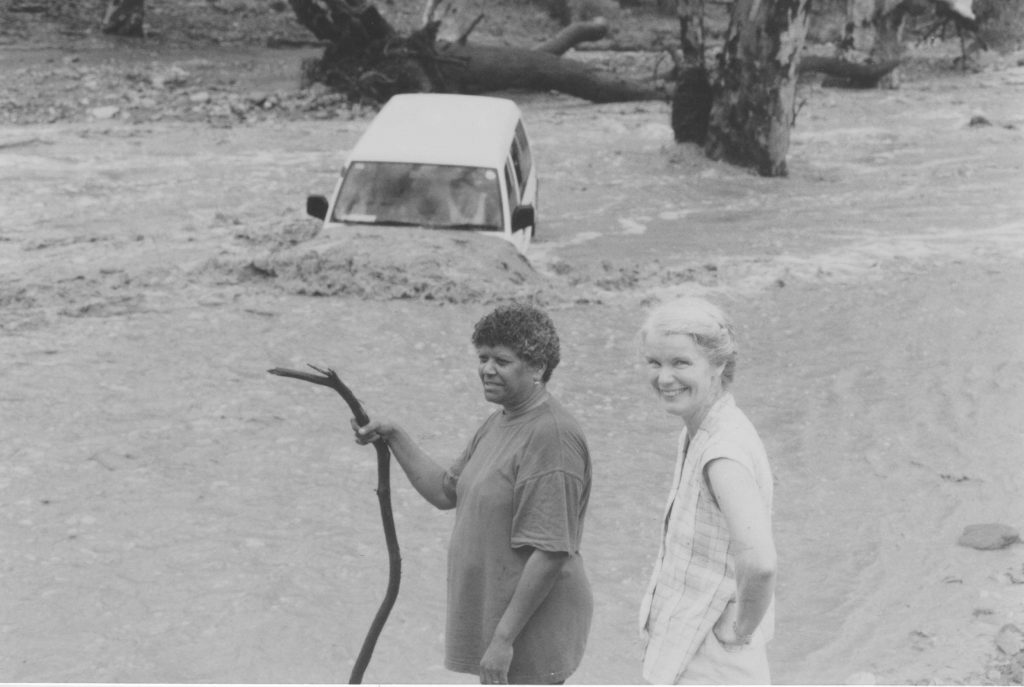

The Rev’d Dr Imelda O’Loughlin with Aboriginal Health Worker Marge stuck at a flooded crossing in Nepabunna, South Australia in 1997

The above photo was taken in South Australia at a place called Nepabunna. We had crossed the dry rocky riverbed in convoy earlier in the day on our way to a clinic. Within hours, the river was flooded from rain higher up in the catchment area. The first vehicle driven by our Aboriginal health worker, Arnold, was washed away and lodged downstream on a large submerged rock. I was driving the second vehicle, along with passengers Graham, my husband, and Marge who was also an Aboriginal health worker. It started to rain a little and I was cold so I asked Marge to light a fire. Her prompt reply was “I’m not that sort of Aboriginal”, so we shivered until a car overflowing with young, boisterous, confident Aboriginal men came to our rescue. They lit a fire for us and then waded into the raging torrent taking a rope to Arnold. Slowly, but surely, we were all taken across the river and then miners from Leigh Creek picked us up to offer hospitality overnight.

I have no doubt that the greatest gift from that time in my medical career was what I learnt about myself. Medicine taught me humility. I walked with people through sad times, exhilaratingly happy times, frightening times, times of great courage and times of despair, funny times and grateful times. I was invited into people’s most intimate lives and thoughts. I was trusted. In the post-modern world, we seldom ascribe power to others based solely on their position. So doctors no longer have the final word in matters of health, no longer dictate treatment options, and are seldom afforded a title, while they watch their para-medical colleagues encouraging the formal appellation of ‘doctor’. Doctors are now often viewed with suspicion and sometimes even hostility.

And, so it is in the priesthood. I am saddened by this – not so much through sense of loss of self-importance or public esteem, but more because of the cost to us all. It becomes more difficult to reach out to someone in distress, to reflect openly on a spiritual journey, to guide public opinion, to have one’s voice heard, to exercise one’s sense of calling. Difficult, yes, but impossible? No. Just as I can’t go back to my previous life, the Church can’t go back to its apparent heyday either. However, I can choose to walk on, acknowledging the Spirit in my life and working to influence, through my words and actions and prayers, a world that I diagnose as seeking to heal a giant hole in its heart.

Thoughts from an intensive care doctor in a privileged society – Dr Gemma Dashwood OAM, intensive care doctor and Diocesan Council member

It occurs to me that the privilege of living in a first world country means that modern medicine can offer various options for treatment that can only be dreamed about in places that are less well resourced. In that way, World Health Day will mean very different things around the world. I suggest we should never take our health, or the medical treatment available to us, for granted.

Any Intensive Care Unit in Australia offers life support for those who are critically unwell, and the more specialised centres are able to implement more extreme treatment such as extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (where all the blood from the body is removed and filtered through a machine which performs the role of lungs and the heart before being returned into the blood vessels of the patient). Heart, lung, kidney, liver, and even pancreas, transplants are also being performed regularly. As well as this, we are given the autonomy to make our own decisions from the various options that first world medicine offers us.

However, with the benefits of modern technology come also the ethical challenges. How can one country justify the expense of keeping a single patient alive for the cost of the entire health budget of a lower income country? How long should we continue with maximum invasive treatment? When is it time to admit futility and withdraw invasive life supporting measures? And how do we know if we are making the right decisions? Most of the time we don’t know the answer to any of those questions. Sometimes all we can do is our best, and offer the rest up to God for Him to take care of.

Perhaps in the end, what is more important than all the fancy machines and the expensive drugs is what happens when you actually meet the patient. Whether in a luxury hospital or in a dirt hut in Africa, the most vital treatment is offering respect, compassion and empathy.

World Health Day gives us all a chance to be grateful for the opportunities we have to be kept well, or the second chances at life we might be given thanks to advanced modern medicine. And when there are no options left for our time here on earth, may we accept the promise of eternal life that our faith offers us with thanksgiving and grace.

Dr Gemma Dashwood OAM in the Intensive Care Unit of The Prince Charles Hospital, awaiting the arrival of the next patient