Three Anglican priests, 10 siblings, a dog named ‘Satan’ and hundreds of letters

Features

“Picture, if you will, a large extended family on holiday in Porlock, Somerset, in the south west of England. The date is August 1906 and the family have taken rooms at Birchanger Farm for a month where they have been enjoying excursions, bicycling, walking and bathing,” writes Frances Thompson following her discovery that the famous Bodleian Library holds hundreds of her family’s letters, dating back to the early 1900s

Introduction

Frances Thompson remembers her grandfather writing a letter to his cousins in the 1980s for ‘The Budget’ (a series of letters full of news collectively written by different people), but at the time she didn’t know that the letters dated back to 1906. A decade later Frances learnt, from her Aunt Judy, that the collection of letters dated back to her great-grandfather’s generation and were in Oxford at the Bodleian Library, one of the oldest libraries in the world. Frances first gained access in 2007 (not easily done), but could only spend one day at the library, as she was on holiday with small children. She quickly realised that a fascinating 80-year social history had been preserved, and that more library visits would be necessary – this took some planning, considering the Bodleian is 16,000km from Brisbane, where she lives.

Meet the 10 Cox family siblings

Picture, if you will, a large extended family on holiday in Porlock, Somerset, in the south west of England. The date is August 1906 and the family have taken rooms at Birchanger Farm for a month where they have been enjoying excursions, bicycling, walking and bathing.

This is a story of the Machell Cox family; told through the hundreds of letters that the siblings wrote to each other, starting in 1906 and continuing until the 1980s.

Advertisement

Let me introduce the family to you. The Rev’d Dr John Charles Cox and his wife Marian have 10 children, who grew up playing cricket and tennis all day long, cared for by domestic servants. They live in the large 19th century Victorian

rectories adjacent to the rural Anglican churches in the villages where their father ministered for nearly 20 years. Enville, Barton-le-Street, then Holdenby. By 1906 the 10 children are now adults, the British Empire still holds sway and three “foreign brothers” live in “the Colonies”, leaving seven siblings in England. Neville works for the railways in South Africa, Wilfred builds roads in British Columbia and The Rev’d Aldwyn is an Anglican missionary in Nyasaland in Africa (now Malawi) ministering to the local Indigenous people.

In England we have Enid, Edmund (another Anglican priest who later named his dog ‘Satan’), Arthur, Bernard, Cuthbert, Avice and Vera; seven siblings aged between 22 and 37.

“The wedding photograph of the eldest sibling, Enid, in 1892. The photo was taken on the tennis lawn, outside the Rectory in Barton-le-Street, Yorkshire. The five youngest siblings are immediately in front of Enid, their sister, the bride. Three boys seated (Aldwyn, Cuthbert and Bernard) and two small girls standing (Avice and Vera) (Image courtesy of the Bodleian Library)

Mother is a kindly, staid Victorian woman in her 60s, terrified of modern motor-cars, accustomed to servants and a life of privilege; yet able to run a household of servants and multiple children, whilst patiently dealing with her difficult clergyman husband who could never be described as a “modern man”.

Father can be tyrannical; he is a born controversialist with a flaming indignant passion for causes he feels to be unjust. In his younger years he was a politician, campaigning for improved rights for the agricultural labourer.

Advertisement

His character developed during his Derbyshire political days in the 1870s, he is a fount of knowledge with regards to Derbyshire churches, as well as being a noted antiquarian. He somehow found time, in between publishing books, to be an Anglican parish priest. Now retired, still publishing books as well as writing for The Church Times newspaper and The Reliquary periodical, he is a kindly but stubborn man with a great dislike of housemaids who attempt to tidy his study.

Back to Porlock in Somerset. If you have been to Somerset, you will know that it is green and idyllic. It is a sunny August afternoon in 1906, as long ago summer days always seemed to be. The family members are in a meadow near Porlock Weir with a picnic; the older generation (including several maiden aunts) are reclining under parasols with lemonade, whilst the younger generation are playing cricket.

“Cuthbert, you’re out,” calls Vera, looking hot and dishevelled and distinctly un-ladylike. She would rather be playing hockey, but cricket is an acceptable second-best.

Avice is exhausted after getting 10 runs but knows she can’t give up and be the one to let the side down.

Meanwhile Dr Cox, Father, climbs over the stile and joins the group. He has just returned from visiting the church in the next village, Luccombe, where his own father was the parson, many decades ago. Dr Cox has just walked through the garden adjacent to the church, for old time’s sake, with its three alternate paths leading from rectory to church, named ‘low church’, ‘high church’ and ‘broad church’. The Rev’d Cox senior named the three paths whilst Dr Cox was still a small boy; the affectionate titles appeal to his argumentative personality and make him smile.

Dr Cox pats his pocket to check his notebook is still there. He has been making notes on Luccombe church for his next book English Church Furniture, which his friend Algernon Methuen will publish in 1907. There is nothing that Dr Cox enjoys more than exploring a country church and making notes on the fabric and furnishings. It is an essential activity to be completed on every holiday, in every county. He can easily lose a day reading the registers in the vestry as well. Dr Cox has not yet completed How to write the history of a parish and is still unaware that his book will be a runaway success in the world of the Anglican Church 100 years ago.

Dr Cox looks at his sons, daughters and nieces playing cricket. It is quite a recent thing for upper-class families to allow their daughters to play sport and to ride a bicycle. Dr Cox wasn’t sure at first, thinking it would affect their marriage prospects, but his wife, Minnie, convinced him otherwise. It is just as well that he did, as Vera will soon be made captain of the England Ladies’ hockey team, and Dr Cox will brag to all his friends about his daughter, “the International”.

Cuthbert enjoys cricket and likes to think he is athletic; he is a schoolmaster at Berkhamsted and plays football for the Old Boys team, but it is awfully hard work keeping up with Vera.

Their cousins Ka and Hester reluctantly join in; neither are as keen on cricket as Vera. Ka Laird Cox is preoccupied with thoughts of the place she has gained at Newnham College, and going up to Cambridge at the start of term. It is a radical thing for a young woman to be going up to university in 1906, but she is already a feminist and will soon become a supporter of the suffragettes. Ka doesn’t yet know that she will soon meet the poet Rupert Brooke, embark on a tempestuous relationship with him, become a member of the wildly unconventional Bloomsbury Set and generally shock and alarm her traditional Anglican family.

Bernard is out, LBW. He mops his brow with his handkerchief; his noble moustache is damp and glistening. Bernard is a London stockbroker and is not as fit as some of his brothers and sisters. He wishes Neville was with them – he is a good cricketer. Next year, Bernard. In 12 months Neville (sibling number four), will be home from Africa on leave and you will be able to play cricket with him then.

Vera is the youngest of the 10 siblings and a very good bowler. She is very athletic and can outrun all her brothers. She could out-cycle them, too, if it wasn’t for the long skirts she is obliged to wear.

“August 1910 – the siblings have cycled to meet their cousins, the children of Bishop Leeke, Bishop of Woolwich, who are on holiday in a gypsy caravan with a horse borrowed from the grocer’s shop in Sydenham. Cuthbert and Arthur are on the left. Bernard is on the right. Vera is in the centre – that’s her bicycling outfit…” (Image courtesy of the Bodleian Library)

Dorothy is next up to bat. She is married to Arthur, who holds position number three in the family, after Enid and Edmund. She watches intently as Vera prepares to bowl, then at the last moment changes her hands and her position and bats lefthanded, to howls of protest from the fielding side.

“Dorothy, that’s just not on!”

“Arthur! We’ve had this discussion before!”

Arthur shrugs his shoulders whilst Dorothy grins, watching the fielders scramble to locate the lost ball. His wife is very much the ‘modern woman’. She does things her way and there’s little he can do about it, even if he wanted to, which he doesn’t. Arthur is a big fan of cricket and contemplates how it is much more enjoyable to play with the family than it is to teach cricket to small boys at Garfield House School in Plymouth, where he is both Headmaster and owner.

Later that evening, they can be seen through the window of the comfortable farmhouse drawing room as Cuthbert entertains the family by singing a few songs in his fine baritone voice, and Avice plays the piano. With no TV or radio or social media, families make their own entertainment. The maids have cleared away the meal and Mother is talking about her idea that her children should begin a Budget, as Avice and her fellow students from teacher training college have done.

Readers, you are probably perplexed as to what a ‘budget’ is. Let me explain. In the 1800s the word ‘budget’ referred to a collection of news or letters. The Pall Mall Budget used to be a London newspaper. So a ‘family budget’ was an ongoing collection of letters sharing family news that was circulated around, and written by, different family members. The use of the word ‘budget’ to refer to government financial plans came later.

“But Avice, your students start their budget with ‘Dear Beetles’ or ‘Dear Buttercups,’ protested Cuthbert. He is a schoolmaster at an expensive private school, and thus finds such things silly.

“You can write ‘Dear Family’, or ‘Dear Brothers and Sisters’,” says Mother patiently, “I am not as young as I was, and I will not always be able to write a letter each week to every one of you.”

“But I like your letters, Mother,” says Avice.

“Mother will continue to write to us,” explained Bernard, “but our family budget will just be for the brothers and sisters, not the parents.”

“Humph. Sounds like a lot of nonsense.” Father is not impressed.

“Enid will be delighted with the idea,” states Vera, who is always matter-of-fact.

“But what about Edmund?” (Neither Enid nor Edmund – the two eldest siblings – are spending the August holidays with the family in Somerset.)

“That is precisely the reason for my suggestion,” Mother explains to her children.

“I have been worried about him ever since he travelled to Kansas and became a cowboy, and then there was that terrible shotgun incident during the Opening of the Cherokee Strip.”

“I was surprised he came back and decided to enter Holy Orders,” declares Father, “I thought he was happy running a store in America.”

“But he did return,” insisted Mother, “He somehow passed his compulsory Greek, he likes his parish in Derbyshire, despite no one else of his class living nearby. But most of you rarely see him. Enid hasn’t seen him for years and he is losing touch with you all. I will write to him and insist that he participates.”

And if a Victorian matriarch declared something would happen, it generally did.

The Family Budget was started in September 1906 by Bernard, who wrote the first letter and then posted it on to Cuthbert, who then wrote a letter and then posted both on to Arthur, and so it would continue. Vera wrote a letter, then Avice and then finally Enid, who was last on the list. The package of letters would then be despatched by Enid back to Bernard, who would then begin the next round. Each sibling wrote with their own news, whilst also commenting on everyone else’s news.

Letters would be despatched to the “colonial brothers” in British Central Africa, South Africa and British Columbia, telling them of the new family enterprise. All three loved the idea, and eagerly awaited each Budget being posted abroad for them to read and contribute to, in turn. Disastrously, some Budgets are lost in the post; the Budget becomes a living, breathing creature to the siblings, and they grieve each loss acutely.

Edmund, my great-grandfather, would be told by Mother that he was obliged to join in. He would also be informed that, like the others, he would have just one week to read the letters, write his own contribution and then post the parcel on. He agreed, joining the Budget in its second round, in October 1906. Entertainingly, Edmund became a real delinquent, forgetting to write and was regularly told off by his younger brothers and sisters for taking too long. The 10 contributors developed a life-long habit of writing for the Budget.

Spoiler alert: the siblings wrote Budget letters for the rest of their lives. As they died, their children continued the habit, and the last poignant letter was written in 1987.

“I like this idea,” mused Vera, “We can tell each other all our news. I shall tell you all about hockey, Bernard will tell us about the Stock Exchange, Arthur and Cuthbert will tell us funny stories about what the schoolboys get up to.”

“Enid will tell news of Liverpool, Edmund will talk about what happens in Derbyshire and Avice will describe all her little dodges as a governess,” continued Mother.

“As long as no one criticises my handwriting,” said Cuthbert firmly.

Arthur grinned. He was an entertaining and clever wordsmith, excellent at poetry, and he thoroughly enjoyed writing long and informative letters, but he knew Cuthbert’s handwriting to be generally diabolical. He was already eagerly anticipating the entertaining criticisms that were bound to arise.

“I like the idea of writing one letter which goes to everybody. That seems so much easier than having to write so many letters to all of you.” Avice already thought it was a good idea.

“But you never do, Avice, although you do really mean to,” declared Vera. “You must admit that you are disorganised and always late and that you rarely get around to writing to us.”

“That’s true,” lamented Avice, to peals of good-natured laughter from her family.

Author’s concluding notes:

20 years ago my aunt told me about a pile of family letters in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England. So far, I have only read a small portion. I still have another 50 years of letters to read, when air travel opens up and I can return to Oxford again. A fascinating prospect – I have many more tales to read about ‘my’ 10 siblings.

Whilst I am enjoying writing about the 10 siblings whom I have introduced above, I get distracted when the post arrives with a second-hand eBay book written by Dr Cox, my great- great-grandfather, 100 years ago. I am finding him a fascinating character, who surprisingly detested carol singers, and used to chase them from his porch. He wrote widely on churches, but I must admit to being perplexed as to how it is possible to write a whole book just on bench ends.

I am currently reading all of the letters written by Aldwyn, sibling number seven, who lived and worked in Africa for 56 years as an Anglican missionary with the Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA). In 1892, aged 12, Aldwyn read a book by Livingstone, the great African explorer, and decided to go to Africa and work as a missionary when he grew up. He goes on ‘ulendo’ (travelling) between African villages, helping to sort out marriage disputes and bribing villagers to build a school or a church by shooting game for them to eat. He learns to deal with the tribal issues of witchcraft and slavery, as the Mission builds hospitals and schools and encourages the villagers to educate their girls as well. He and his colleagues listen to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on the radio, having somehow obtained new batteries the week before. “God Bless our new Queen,” says Aldwyn in 1953.

Along the way I have made contact with an African bishop in Malawi, writing a PhD on the church history of his diocese. He is very keen to find out what I have discovered about this English missionary, who died 60 years ago at St Peter’s Cathedral on the island of Likoma, in his diocese.

My great-grandfather, Edmund, sibling number two, was another Anglican clergyman, who spent 39 years in the same parish, baptising, marrying and burying the villagers of a Derbyshire working class community. Sadly for me, he is not such an interesting character. He struggles to make friends, as no one of “his class” lives nearby, and probably suffers from depression. His letters pale into insignificance alongside his more intelligent, vivacious and fascinating siblings. However, I wish I could ask him why on earth he named his dog ‘Satan’.

I am currently working on a podcast, which I will be launching soon, called 100 Years of Cox, in which I will be reading ‘The Budget’ letters. If you would like to find out more, please email me via machellcoxletters@gmail.com.

Two ‘Budget’ letters (written by Bernard and Cuthbert)

Bernard is the eldest of “the younger family”, followed by Aldwyn, Cuthbert, Avice and Vera. Aldwyn is an Anglican priest and in the summer of 1906 has just sailed for Africa, and a new post as a missionary. He will be working in Kota Kota in Nyasaland, now modern-day Malawi.

Cuthbert is a schoolmaster at Berkhamsted School, which in 1906 is still quite a small school. Cuthbert went to Berkhamsted School as a schoolboy, then spent three years at Magdalen College Oxford, then went back to Berkhamsted School as a Master. He later becomes Headmaster, and then a Governor, and never leaves.

Bernard, 29, Threadneedle St, London, 19 September 1906 (Budget No.1)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

I have been asked by a portion of the family to start the “Budget” on its travels, so here goes.

The Budget will make its way around England and once all letters have been read by the “home” members, a package will be despatched to Aldwyn and Neville. Before Aldwyn’s sad departure for Africa (tearfully farewelled at Folkestone by the little girls, Cuthbert and myself) he expressed his deepest desire to be kept informed as to the family perambulations and news.

I have written a letter to Wilfred and am awaiting his reply regarding his involvement. Mother has written to Neville.

You will probably think that I cannot be very busy, as you note the address of our offices above, and you will be right. Business on the Stock Exchange just now is non-existent. If any of you want to make a change in your investments, please hurry up and contact me, as Messrs Hunt, Cox and Co. will be pleased to advise. I expect I shall now be told by various budget members not to write shop, or not to advertise! We have two new clerks and it remains to be seen whether they will be acceptable; as to one of them, I have my doubts.

There is very little news from home. Our holiday party has broken up. Cuthbert returned to Berkhamsted last Sunday, and Avice to Hertford yesterday. Perhaps some of you may like to hear about the winter clothes which she purchased from Enid’s dressmaker in Liverpool. She has two perfect ducks of hats. One is black beaver and the other I cannot describe, but the general effect is blue. It has a very saucy shape. She has also had a new coat and skirt made, with which, an unusual thing for her, she is quite enraptured. The colour has been variously described as purple, heather, maroon, heliotrope and mahogany, also beetroot. She will be able to tell you herself which colour is correct. It is very well cut and shows off her admirable figure to advantage. Another purchase is a flannel blouse with a detachable flannel collar. This pleases her very much although she was rather afraid she looked like Vera! Doubtless there are other garments, but these are all I know of. I don’t think Vera has prepared for the winter yet, beyond embroidering a little white horse to wear on her hat when she plays hockey for Kent.

Mother has bought a new smocked waterproof of the usual shape and hue. I believe a new hat arrives today which will be very exciting. Our great anxiety is to know whether it will sit straight.

Poor Father is suffering from severe headaches, which come on regularly every evening about 7 o’clock. He is trying various remedies. Arthur will be interested to hear that the very latest is Oxo. Father had a great to-do in the hallway yesterday, as Gladys continues to attempt to clean in his study, and Father insists that he will not have it.

A long and interesting letter arrived from Aldwyn last night. He seems to have had a rough time of it during the latter part of the journey to Africa, but it is pleasant to note his highly developed sense of humour. The lost cork of Miss Parson’s tea-bottle seems to have caused him as much amusement as the old Portuguese man’s abandoned fruit.

It is always tiresome to return to the office after a perfectly delightful summer holiday spent in the bosom of one’s family. I do believe that Birchanger Farm was an extremely good location and I enjoyed the many excursions. The bathing was excellent as indeed was the cricket, and our rooms were first-rate; even Cuthbert was on his best behaviour. Arthur brought his usual collection of threadbare trousers and Avice continued her habit of being late to breakfast.

I believe we are to make use of the budget for passing on the names of interesting books. Here are some I have lately read –

The Viper of Milan – M.Bowen – very good

The Fifth Queen (of Henry VIII) – F.Madox Hueffer – Decidedly interesting. Should like to read a sequel to it, though I am told that the heroine became too bad for more to be written.

Dick – G.F. Beadby – a Rugby boy on his summer holiday in Norfolk. Delightful.

Voyage of the Discovery – Capt. Scott – If any of you have not read this, get it now if you care at all for travel and exploration. The most interesting book of the sort I have ever read. (South Pole)

I greatly anticipate reading the literary outpourings from my dearest brothers and sisters and eagerly await the return of this budget to me, at our humble abode of St Alban’s.

Your affectionate brother

B. Machell Cox

Cuthbert, 2 Chapel St, Berkhamsted, 22 September 1906

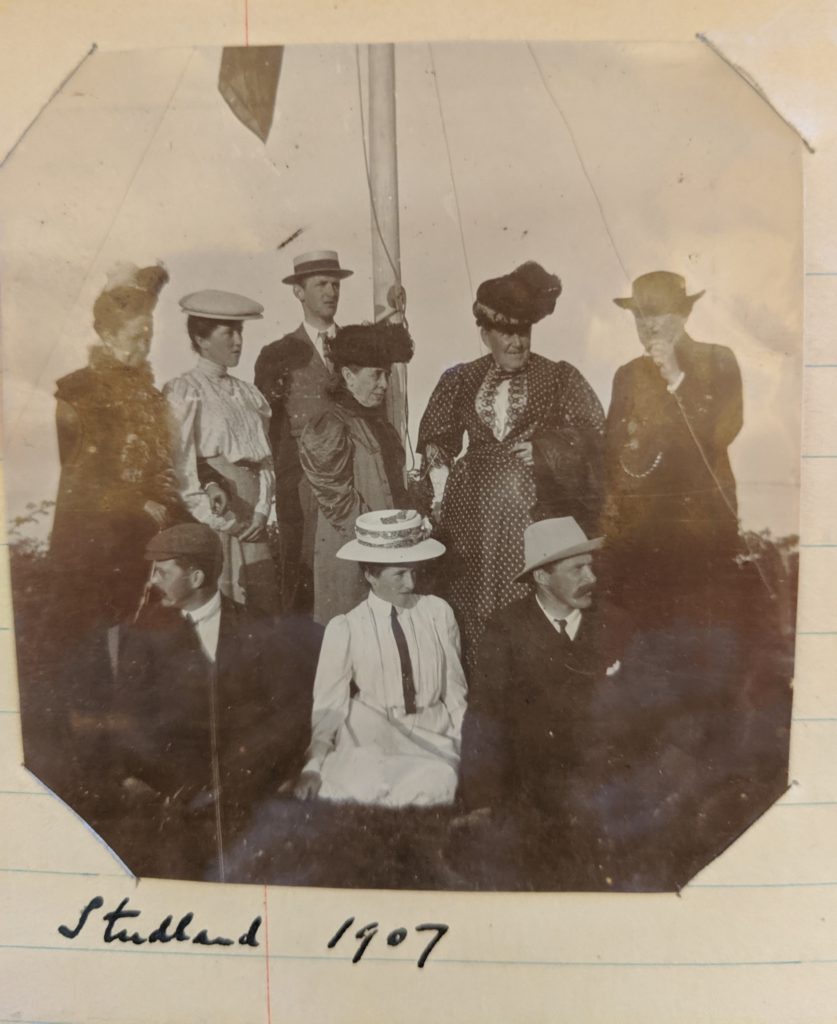

“1907 summer holiday at Studland in Dorset. In the front row (L-R) are Bernard, Vera and Neville. Mother stands next to Vera. Cuthbert is immediately behind Mother. Father (The Rev’d Dr Cox) is on the right” (Image courtesy of the Bodleian Library)

Dear Family

I am enthusiastically enjoying this budget already and indeed, although I have only recently seen many members of the family, I am pleased to promptly receive news from Bernard. I am writing my letter early, so as not to be late and over-run my week’s allowance.

Here is rather a neat bon mot for you. A certain boy in the Junior School here has been a perpetual nuisance for some two terms and has again and again been threatened with expulsion. Well he met his fate the other day and the Head of the Junior School told the boy’s long-suffering form-master the welcome news in these words: ‘Psalm 37, verse 39’, which is: “and the end of the ungodly is they shall be rooted out at the last.”

Our senior maths man is supposed to be a genius, and is certainly mad, and the stories of his doings are the chief topic of conversation on the staff. (The boys by the way call him ‘Bunions’ because of his extraordinary walk). He is horribly absent-minded and was discovered the other day standing in front of a public-house he has to pass on the way to his rooms, busily correcting papers and whistling, quite oblivious of the fact that there was quite a crowd looking on and laughing. Honestly this is not exaggerated in the least. He is far too awful both in manner and experience to be a school master and I hope he won’t stop long. Imagine him standing around outside a public house, it is quite too entertaining for words.

I have joined Smith’s Library here and have read several books which though no longer new, were new to me.

Salted Almonds – F.Austey – very amusing, mostly from ‘Punch’

The Viper of Milan – M.Bowen – a very delightful book

The man from America – Mrs de la Pasture – an extremely pleasant book

In the Days of the Comet – H.G. Wells – pedantic and stilted, one of the dullest books I have read in a long time. I am interested in what others think of this book.

Vera, I am sure you will be interested to learn that I have just ordered a new suit from a new tailor – the reasons for the change are obvious. It is a perfectly sweet thing in tweed, but there I must not begin on this subject as my pen is running dry.

Your affectionate brother

Cuthbert M. Cox

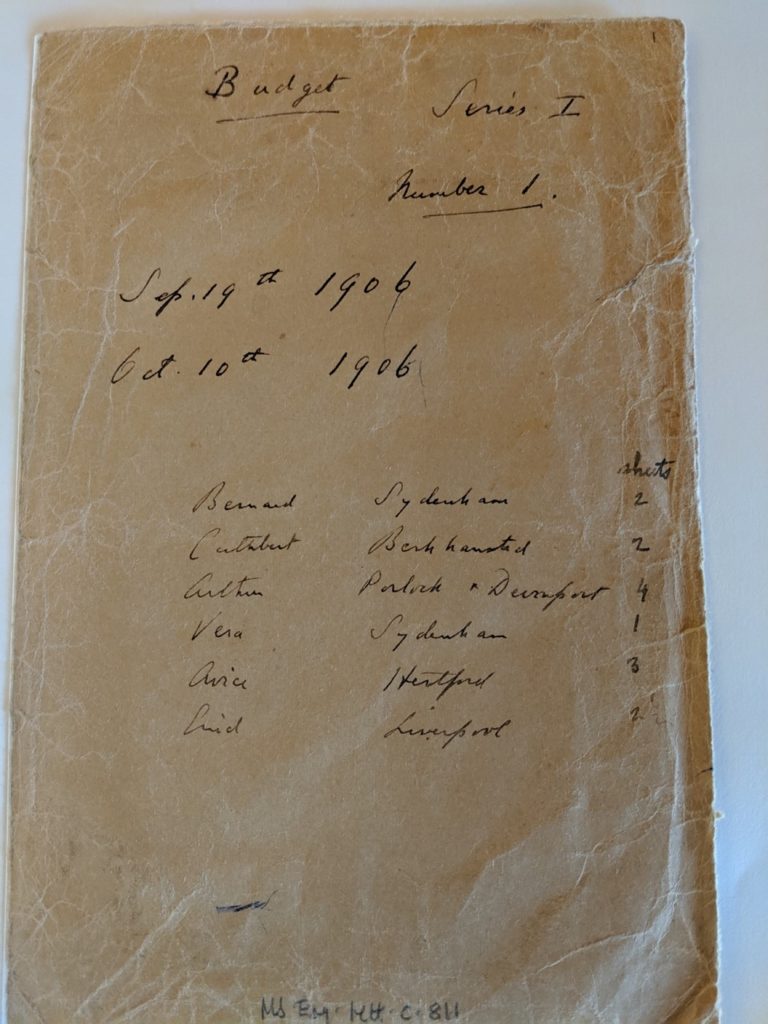

“Each edition of The Budget, consisting of many sheets of notepaper, was stored in an envelope. This is the original envelope from the first edition of The Budget, dated 19 September 1906, listing the names of the six siblings who wrote a letter for the first Budget, and their address (e.g. Bernard and Vera were both at home in Sydenham and Cuthbert was in Berkhamsted)” (Image courtesy of the Bodleian Library)