A Christian reading of David Campbell’s poetry

Reflections

“I find Campbell’s work increasingly powerful as an expression of not only a spirituality of creation, of this Australian continent, but as a theology of creation that works on the reader at the level of participatory symbol,” says The Rev’d Canon Dr Ivan Head of poet David Campbell (1915-1979)

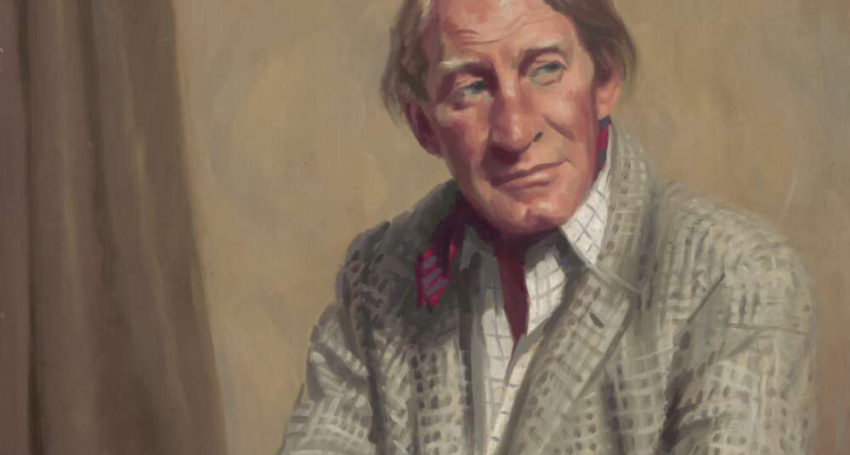

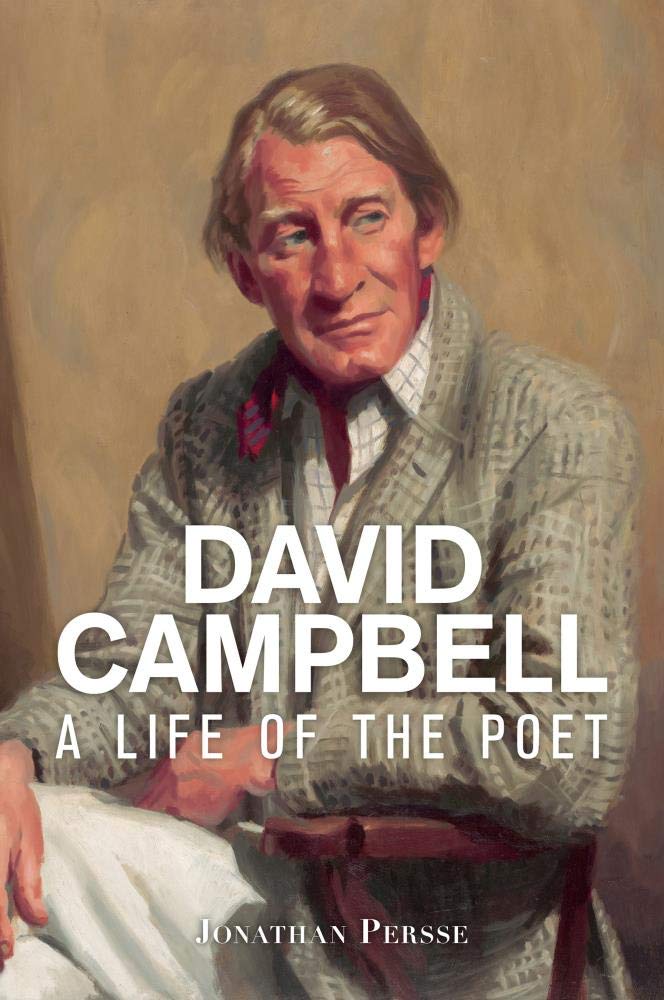

I recently read Jonathan Persse’s excellent book David Campbell: A Life of the Poet. Campbell lived between 1915 and 1979 and I leave the personal biography of this distinctive Australian to the reader’s further interest in Persse’s book. Campbell’s poetry itself sharpens the question of an Australian spirituality.

One cannot use the phrase ‘Australian spirituality’ today without thinking of the more complete dimensions of Australian spirituality that embrace and are immersed in the long tradition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures – and which will remain and endure in the landscape and in the heart so long as one form or other of detonation is resisted and made impossible. While Campbell wrote poems about Aboriginal spiritual practices and rock paintings, this is not the occasion to discuss these, nor what he encountered of the world’s longest continuously living culture as an observer.

Born on the land in the Monaro District of the Southern Highlands of New South Wales into a professional and grazier family, the Australian landscape had an increasing effect on him. It became the vehicle for something other than landscape itself. His poetry expanded from a controlled and disciplined bush ballad style to include a mysticism of the intellect that responded deeply to what human life generated in its natural setting. I find Campbell’s work increasingly powerful as an expression of not only a spirituality of creation, of this Australian continent, but as a theology of creation that works on the reader at the level of participatory symbol.

Adelong Creek: David Campbell was born near Adelong, NSW in 1915

In the symbol, at least two somewhat different things are brought together, as the literal meaning of this ultimately Greek term tells us: indeed the symbolic is the opposite of the diabolic which is literally that which is thrown apart. This pair of terms is redolent of Gospel texts.

That a poet may genuinely bring things together and hold them together in the human heart, or help hold the heart together, is a great thing in an Australia today where our young in particular experience too much of a world in which the drive is to tear or throw apart and to experience the diabolic. As the great Irish poet Yeats put it in his poem ‘The Second Coming’, “the centre cannot hold”.

Advertisement

God reconciles us as Christ indwells us. This is part of what Tyndale meant by ‘at-one-ment’. Hitherto, life had been marked by separation and apart-ness, even by hostility and enmity. Now it is marked by a new unity in Christ, an ongoing relational reality.

In their specific attention to detail, Campbell’s poems raise the mind and heart to the realm of the Spirit of Christ, who draws close to us, deep within us, abiding in and indeed communicating with each of us who seek to participate more fully in the gift of the God who is for us – as any careful reading of Romans 8 makes clear.

The reader can find Campbell online and browse from the 635 poems that were his life-time contribution in verse. Most of us will not put hours and hours into that so I suggest that one follow the path taken by Kevin Hart (a poet who knew Campbell in the early 1970s in Canberra) in his The Oxford Book of Australian Religious Verse. Hart selected these poems written by Campbell for his anthology: ‘Far Other Worlds’, ‘Speak with the Sun’, ‘The Miracle of Mullion Hill’, ‘Fisherman’s Song’, ‘Among the Farms’, ‘Sweet Rain’, ‘Trawlers’, and, ‘A Yellow Rose’.

Advertisement

Here are some lines for you to ponder.

From ‘The Trawler’:

“And the John Dory at this silver hour

Still bear Christ’s thumb-marks

his blessing at Galilee.”

From ‘A Yellow Rose’:

“Mass

At the speed of light

Is a yellow wafer.”

And powerfully and thematically from ‘Far Other Worlds’:

“A white wind turns the daylight moon

And Time is whittled on that stone…

And griefs dog – buried into that land

Shall stand up green between the stone.”

Campbell’s mysticism of the precise, and his detailed attention to this world as it is experienced, draws in part on his engagement with modern physics and the pursuit both of the nano and the macro, and the relationship between all the larger constituents of reality and the infinitely small realm where energy and matter seem to oscillate. ‘Mass at the speed of light’ has a meaning in physics even as the Christian thinks of participation in Christ.

Between the nano and the macro, we ask about the middle and in-between state of being human, of the realm of the Spirit and of resurrection. Thus we attend carefully, when in his 1948 poem ‘Speak with the Sun’, we read:

“From a wreck of tree in the wash of the night

Glory, glory, sings the bird…

Now from deepness of the glade

Well up the bubbles of delight:

Of such stuff the stars were made.”

For the Christian? We are reminded powerfully that God is the author of all creation – creation in all its brilliance and diversity, from the tiniest to the largest. And, that new knowledge of reality should inspire and not intimidate. It should also keep us humble. The God who sustains the incomprehensibly powerful plasma furnace of the sun, second by second, and through the mystery of time, must also be the God of Jesus Christ. Knowing both to be true, we reduce neither to doggerel.

Jonathan Persse’s David Campbell: A Life of the Poet is published by Australian Scholarly Publishing