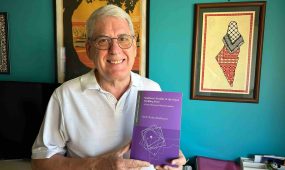

On Being Blackfella's Young Fella: Is Being Aboriginal Enough?

Books & Guides

Clergy and lay people each reflect upon a chapter of Wiradjuri man and Anglican priest The Rev’d Glenn Loughrey’s recently published book, On Being Blackfella’s Young Fella: Is Being Aboriginal Enough? In doing so, they consider how the book’s insights will shape their approaches to Reconciliation

In this special joint reflection, clergy and lay people each reflect upon a chapter of Wiradjuri man and Anglican priest The Rev’d Glenn Loughrey’s recently published book, On Being Blackfella’s Young Fella: Is Being Aboriginal Enough? In doing so, they discuss why their chosen chapter resonated with them and consider how the book’s insights will shape their approaches to Reconciliation in the future.

“I, too, am an Anglican priest and an Aboriginal man. I have not yet come to terms with the inner struggle and the tension that must be lived with. Glenn seems to be able to live in that tension” (The Rev’d Canon Bruce Boase, Wakka Wakka man and Co-Chair of the ACSQ RAP Working Group)

Introduction – The Rev’d Canon Bruce Boase, Wakka Wakka man and Co-Chair of the ACSQ Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group

I was drawn to the Introduction of Glenn’s book by the sheer honesty of his writing. Glenn and I have had similar experiences growing up in country areas where our identity was ambiguous as we are descendants of both ‘white’ and Aboriginal peoples. The similarities resonated with me, but I was also drawn to our differences. Glenn has put himself, quite courageously I feel, just where he is. He makes no bones of the conflict in his life as an Anglican priest who grew up experiencing racism because he is Wiradjuri, a nation of Aboriginal people from central New South Wales. I also appreciate Glenn’s close attachment to his people, his history and his land.

Advertisement

What struck me about the way Glenn introduced his book was his courage in acknowledging the struggles in his life. There, again, the similarities and the differences between us emerged. I, for such a long time, did not acknowledge the drunken abuse from my father. When reading the chapter, I sensed Glenn’s love for his father, as I did mine. Still there is the struggle. One difference is that my father was not Aboriginal. My mother was. My nanna was a Wakka Wakka woman from Ban Ban Springs. These two ladies were always gentle.

Glenn is on a journey that is defined by the struggle. I have already touched on the inner conflict he expresses between his Christian life as an ordained man and his Aboriginality. Again here is a similarity and a difference. I, too, am an Anglican priest and an Aboriginal man. I have not yet come to terms with the inner struggle and the tension that must be lived with. Glenn seems to be able to live in that tension. In beautiful and loving ways, Glenn paints the picture of the land he grew up in. He now knows the sadness of seeing that land pillaged for mineral resources. Struggle is always there, but Glenn learns from it and can make us think about our own struggles and journey.

Advertisement

When I encounter another member of an Aboriginal community, I recognise the need to acknowledge the struggle within myself. The ‘whiteness’, if you like, of my upbringing was driven by fear. Mum and Nana feared the loss of their children in a time when Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their parents. Glenn helps me to get in touch with this part of my journey, respect it and to reconcile myself. Doing so will help me move forward and talk to others about Reconciliation.

“Given the ignorance sometimes expressed by the descendants of the ‘white’ invaders of this country regarding First Nations peoples, it is not difficult to conclude that we – I – might want to remain comfortable in holding to existing beliefs and so devalue what others might wish to assert about themselves” (Jean Anderson, parishioner of St Mathew’s Anglican Church, Gold Coast and member of the ACSQ RAP Working Group)

‘In the Good Old Days’ – Jean Anderson, parishioner of St Matthew’s Anglican Church, Coomera and member of the ACSQ Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group

Glenn Loughrey is an artist, and I am interested in art. In my years of outback travel, I made it a practice to bring back pieces of Aboriginal art, craft and fabrics and make them part of my life – as reminders of places I had been fortunate to visit, yes. But also because I loved the strong simplicity of their mark-making – dots, lines and patterns of nature re-imagined and defined with the tools at hand. I have also seen this trait more recently in the individual works of Aboriginal artists included in a few ‘non-remote’ and online exhibitions. But the subject matter can sometimes be uncomfortable for non-Indigenous viewers – particularly in the different interpretations of our shared history – and the opportunity to purchase such works much reduced by lack of exposure.

The Rev’d Glenn notes that, “Art is a way for the white western community to bestow identity on Aboriginal people, to mark who is a real Aboriginal artist or whose art is authentic or not. I know this personally for it’s the question I answer when I enter a gallery – ‘Are you traditional or urban?’ ‘Urban.’ ‘Sorry, only trade in traditional art.’ ” (p.42). Before reading this, it had not occurred to me that some Australians might view the only ‘authentic’ Aboriginal art as that which is created in remote communities, as such works convey what many non-Indigenous Australians might want ‘Aboriginality’ to be. But I am forced to consider this when The Rev’d Glenn suggests that, in our preferences for one over the other, we may be expressing a desire to reconstruct the ‘good old days’ and a simpler way of life when everyone seemingly knew their place within the dominant power structure and acted accordingly. Given the ignorance sometimes expressed by the descendants of the ‘white’ invaders of this country regarding First Nations peoples, it is not difficult to conclude that we – I – might want to remain comfortable in holding to existing beliefs and so devalue what others might wish to assert about themselves.

There is much I am forced to consider in this chapter focused on Aboriginal ways of seeing art and storytelling, and I am uncertain in my understanding of it. But the hope for me in my personal journey of reconciliation is encapsulated in The Rev’d Glenn’s references to ‘reflective nostalgia’, which “looks back at the same period and compares it with now and works to divine truths from both places.” (p.40). The Rev’d Glenn points out that being comfortable with uncertainty is a requirement for the collaborative and continuing work of finding truths in comparisons of past with the present which might open a way to a better future. For me, that is a willingness to embrace opportunities which confront me with other ways of seeing. The Rev’d Glenn’s book is one of those opportunities.

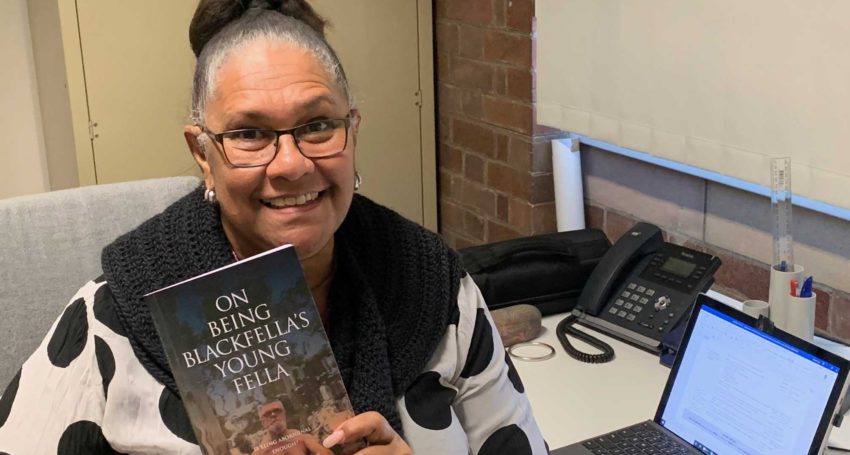

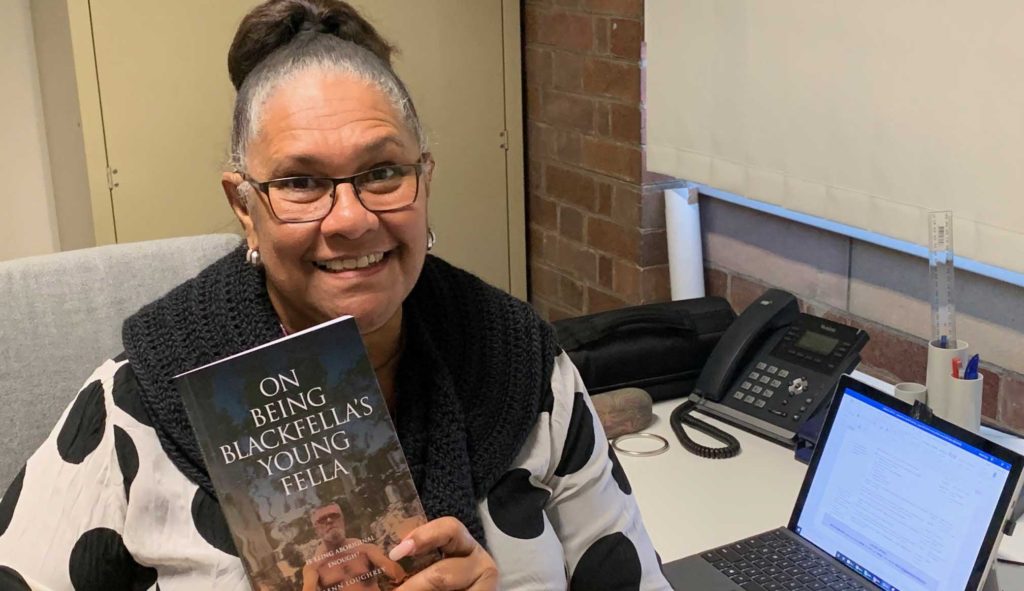

“In my Reconciliation work, telling tangible stories that transcend culture is important and I will remember The Rev’d Glenn’s and my stories in my Reconciliation conversations with people” (Sandra King OAM, Quandamooka and Bundjalung elder and ACSQ RAP Coordinator)

‘The Rocks Speak’ – Sandra King OAM, Quandamooka and Bundjalung elder and ACSQ Reconciliation Action Plan Coordinator

When sister Michelle McDonald asked me to write a response to a chapter of Glenn Loughrey’s new book On Being Blackfella’s Young Fella, it only took a matter of seconds to pick a chapter. I scrolled past the chapters on ‘Aboriginal Spirituality’, ‘A Little Bit of History’, ‘In the Good Old Days’, ‘On Being Aboriginal’, ‘This Ground, She’s My Mother’, ‘Wiradjuri Dreaming’, ‘Repository of Sacred Texts’ and there it was, there was the chapter that got my attention, ‘The Rocks Speak’.

The first paragraph sums it up…the old stories we hear, like those that tell us that country is sacred and that we need to listen to it, learn from it and nurture it. As a child I was often told “throw it back” or “you go to Uncle or that ol’ fella there [an Elder] and ask him if you can take the rock or shell!” Of course, I threw the rocks or shells back.

At my father’s funeral, I realised I had forgotten to do one thing that I knew he would have wanted me to do for him. I looked up and saw my cousin and Elders from Tjerrangerri country (Stradbroke Island) walk in and there it was…my cousin Margie handed me a big tub with a lid. I was so relieved, tears just streamed down my face. Then my Elders told me something so precious, “Your father started this ‘tradition’ and it will continue forever.” This ‘tradition’ is sacred to me as it relates to the burial of our Quandamooka people.

At the gravesites of deceased people of some cultures, family and friends grab a handful of soil and throw it over the coffin. For us, Tjerrangerri people it’s a little different. The big tub handed to me at my father’s funeral held something precious…it was the sand from Dad’s country. We sprinkled the sand over his coffin – to symbolise that country was always with him while he was alive and remained with him when he ‘returned’ to country.

Even though Dad had never returned to country to live (due to the rigid rules of his mother’s Certificate of Exemption, which he was listed on as her child), he was a proud Quandamooka man. He had a strong sense of cultural values and of a belonging, not only to his family members, but a sense of belonging to his country. Hence, ‘The Rocks Speak’.

The experience of sprinkling my father’s grave with sand, further strengthened my connection to country and family, and in a very tangible way. It is common across cultures for funerals of close family members to strengthen connection to family by respectfully filling the gravesite.

In my Reconciliation work, telling tangible stories that transcend culture is important and I will remember The Rev’d Glenn’s and my stories in my Reconciliation conversations with people.

“What struck me most in this chapter were the quoted words of an unidentified ‘Indigenous woman’ who once said, ‘I carry my country in my body’ ” (The Rev’d Dr Jo Inkpin, Co-Chair of the ACSQ RAP Working Group, pictured with fellow RAP Working Group member and Yiman woman Olly Yasso from Anglicare SQ)

‘This Ground, She’s My Mother’ – The Rev’d Dr Jo Inkpin, Co-Chair of the ACSQ Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group

I was drawn to ‘This Ground, She’s My Mother’ for several reasons. It was spiritually inviting, as understanding material existence as spirit is so limited in white western thinking, and female imagery for being is also rare, particularly from a male writer. More importantly, however, I wanted to see how far Glenn’s understanding of ‘country’ differed from and resonated with my own. As someone with strong Celtic spirituality, I am interested in such connections. Having a topographic surname specifically referring to features of another land (in Old English ‘Inkpin’ means ‘people of the hill’, specifically a location in Berkshire, England), I am also aware of my and my own ancestors’ deep, but ruptured connections, with my/our country.

What struck me most in this chapter were the quoted words of an unidentified “Indigenous woman” who once said, “I carry my country in my body”. This holistic understanding of identity importantly helps maintain life for First Nations peoples when off country. It also underpins the helpful distinction Glenn makes between sovereignty and autonomy. Too much he says has been made of principles of the ‘sovereignty’ of people, when it is the land itself that is sovereign, as it is the life-giver. People’s sovereignty may therefore be a necessary legal use of a key term in the dominant culture. However true self-determination is based on the autonomy of country which is an embodied cultural reality.

Glenn’s exploration of connection to country thus happily avoids sentimentality and grounds The Uluru Statement from the Heart and other First Nation rights to self-determination in the autonomy of country itself. Shared spaces and similarities may exist for acting and engaging with others. However, in the words of Sarah Maddison whom he also quotes, the autonomy of carrying country bodily involves “making mistakes, being accountable, and fixing those mistakes yourself” (page 70).

Carrying country bodily suggests to me a greater need for deeper grounding of my Reconciliation work in the particular experiences and cultures of First Nation peoples. Strengthening such connections, literally and metaphorically, is therefore essential. Whilst mediating language, such as ‘sovereignty’, may be helpful at times, supporting the autonomy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is central.

Glenn Loughrey, 2020. On Being Blackfella’s Young Fella: Is Being Aboriginal Enough? Coventry Press, Victoria.