Peering through portholes of nostalgia

Reflections

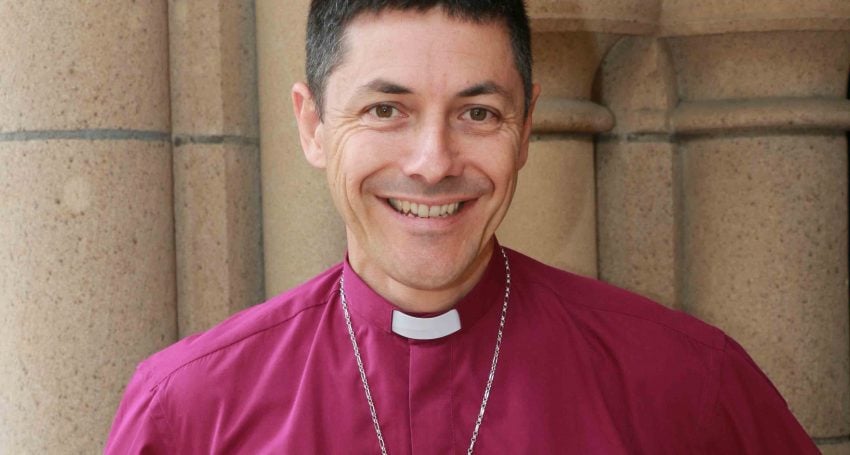

“My granny’s diary is a fascinating account of a six-week voyage with plenty of stops along the way. I re-read it recently while preparing for the Lambeth Conference, which is currently underway in the UK. Her diary speaks of a time long past when life was slower and Christendom was still a reality. Of course, it is tempting to be nostalgic and to long for things to be like that once more,” says Bishop Jeremy Greaves

On February 1st (Thursday) Daddy, Mother and I left Adelaide by the P&O.S.S. Mongolia for England. A great many people saw us off from the Outer Harbour and we were given crowds of flowers, mostly gladioli and carnations, which lasted for several days on our table in the dining saloon.

The ship sailed about 5 o’clock and, after staying on deck until we could no longer distinguish the people on shore, we went to our cabins (50 and 54 on C Deck) and unpacked. I looked out of my porthole every few minutes and saw the coastline gradually fading into the distance, and felt very thrilled with everything.

Advertisement

So begins my granny’s “Diary of a Voyage to England in 1934”. My granny’s diary is a fascinating account of a six-week voyage with plenty of stops along the way. I re-read it recently while preparing for the Lambeth Conference, which is currently underway in the UK.

Her diary speaks of a time long past when life was slower and Christendom was still a reality. Of course, it is tempting to be nostalgic and to long for things to be like that once more:

We arrived at Freemantle at 8.30am on Monday and after breakfast were met by the Archbishop of Perth who took us for a drive in his car; it was a lovely old boneshaker, and Daddy and I were fairly rattled about in the back, however it took us at great speed up to a hill from which we had a glorious view of the Swan River.

In the 17th century nostalgia was considered to be a psychopathological disorder and was first described by the Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer having observed Swiss soldiers who were reportedly so debilitated by a longing for home when they heard a particular Swiss milking song, that its playing was punishable by death.

Advertisement

Some of the soldiers’ nostalgia symptoms included melancholy, loss of appetite and suicide. But other symptoms included hearing voices and seeing ghosts of the people and places you missed. Whatever the symptoms, nostalgia was quite debilitating, and soldiers had to be discharged and sent home when none of the usual treatments worked. At one point it was thought that nostalgia should be treated by “inciting pain and terror” or that it could be cured with “a healthy dose of public ridicule and bullying”.

These days “nostalgia” is associated more with warm memories of days gone by, but it can be debilitating nonetheless. We can spend too much time looking back and be prevented from imagining the future.

In the 18th century, French doctor Hippolyte Petit offered advice on nostalgia that seems as relevant today as it was to a soldier driven mad by a milking song hundreds of years ago:

“Create new loves for the person suffering from love sickness; find new joys to erase the domination of the old.”

How might we imagine a different future for our Church? What are the “new loves” and “new joys” we can invite people into as we seek to tell our story in these very different times?

As the past “gradually fades into the distance” how might we re-capture a sense of missional imagination so that we might feel “very thrilled with everything” once again.