Bunyan’s progress: a dissenter in our midst

Features

“Confession time: when I was asked to write this anglican focus feature about John Bunyan, I had never read The Pilgrim’s Progress. This has, therefore, been an opportunity to treasure, as Bunyan captures his characters so well that we can easily think of people like them in our own lives and sometimes we see them in the mirror,” says The Rev’d Peter Judge-Mears from the Parish of Wishart, as John Bunyan is commemorated in our Lectionary on 31 August

A man was arrested for attending a religious gathering with more than five people outside his immediate family. No, this didn’t happen during this COVID-19 period. It happened in the 17th century to John Bunyan, the author of The Pilgrim’s Progress: From this World to That Which is to Come (or just The Pilgrim’s Progress).

Bunyan was born in November 1628 in Elstow, Bedfordshire, England. He lived through the English Civil War (1642-1651), fighting on the side of the Parliamentarians against the Royalists. Quick history for those who need it: supporters of the king fought supporters of the Parliament with the Parliamentarians winning. Charles I was tried for treason (with questionable legality) and executed. Ultimately, after a time as a republic, the heir, Charles II, returned as a constitutional monarch (king subject to Parliament) and life went on. Tied up in all this were questions of religion and the place, if any, of those who didn’t find a home in the Church of England of the day.

Spring, the Moot Hall; Elstow village: John Bunyan’s birthplace

Following the war, with England a republic, there was a degree of religious freedom. And so Bunyan found himself drawn to a group called the Bedford Meeting, becoming in time a preacher and pastor in that Church. When the monarchy was restored, however, the tolerance of non-Church of England Churches ended and Bunyan was arrested. His original sentence was for three months, but a condition of release was that he vow never again to worship outside a non-Church of England Church and so, unwilling to make that vow, his sentence drew out to 12 years.

Advertisement

It was in prison in 1678 that he wrote his famous allegorical novel, The Pilgrim’s Progress. It is written as the story of a dream and tells the tale of ‘Christian’ who is troubled by the burden of his sin and begins a journey toward Paradise. He encounters perils and distractions, such as the delightfully named ‘Slough of Despond’ (a quagmire that drags you down) and ‘Vanity Fair’ (yes, this is where that famous phrase comes from).

At one point he comes upon the hill called ‘Salvation’ atop which was a cross:

“In my dream, just as Christian came up to the cross his burden loosened from his shoulders and fell off his back. It tumbled and continued to do so down the hill until it came to the mouth of the tomb where it fell inside and was seen no more.

Small wonder this was used by missionaries as a way of introducing the Gospel.

But it isn’t just the joyful images that have inspired readers for so long. The other characters with their not-even-slightly-subtle names like ‘Pliable’, ‘Sloth and ‘Presumption’ show an insight in the things that would make us balk at continuing as Christians. In the Aneko Press edition of this book, the publisher’s description captures Bunyan’s genius here:

Advertisement

“Each character represented in this allegory is intentionally and profoundly accurate in its depiction of what we see all around us, and unfortunately, what we too often see in ourselves.”

I find Bunyan to be a fascinating character, full of zeal for the work of ministry – couldn’t we all do with more of that – willing to suffer years in prison rather than take the easy way out. His writing is, in some ways, what we might expect of the 17th century Puritans, yet its impact cannot be denied.

Unlike other writers of his day, such as John Milton and Richard Baxter, John Bunyan was not wealthy – he was a travelling salesperson, as his father was. His first wife, whose name appears to be unknown, was pious and also poor. Her dowry was two books, which became central to Bunyan’s conversion, these being Arthur Dent’s The Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven and Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety. He became England’s most famous author. Bunyan wrote:

“We came together as poor as poor might be, not having so much household-stuff as a dish or spoon betwixt us both.”

The Pilgrim’s Progress was first published in 1678, sold 100,000 copies within four years and has never been out of print since. His book inspired authors such as CS Lewis, Louisa May Alcott (who wrote Little Women) and Charles Dickens. Samuel Johnson (a literary scholar in the 18th century) said:

“this is the great merit of [The Pilgrim’s Progress], that the most cultivated man cannot find anything to praise more highly, and the child knows nothing more amusing.”

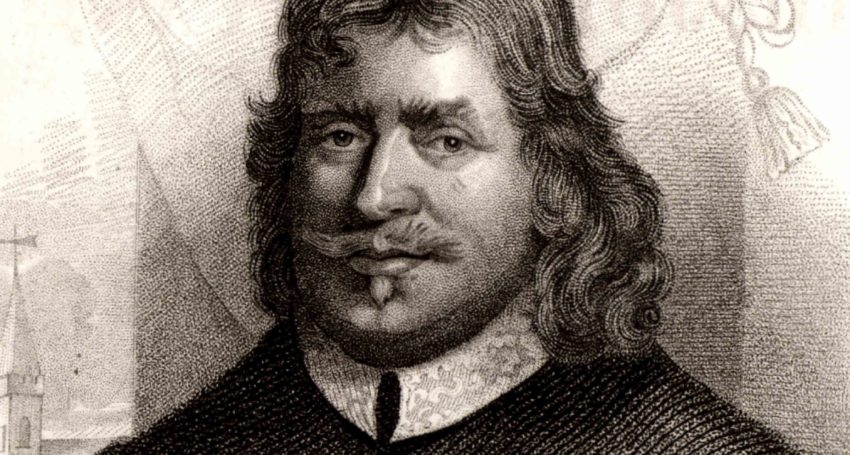

John Bunyan (1628-1688) dreaming of The Pilgrim’s Progress

Confession time: when I was asked to write this anglican focus feature about John Bunyan, I had never read The Pilgrim’s Progress. This has, therefore, been an opportunity to treasure, as Bunyan captures his characters so well that we can easily think of people like them in our own lives and sometimes we see them in the mirror.

The anniversary of John Bunyan’s death, 31 August, is the day he is remembered in our lectionary. If you haven’t given The Pilgrim’s Progress a read, maybe the coming week is a good occasion to change that and see why this dissenter is commemorated in our Anglican calendar.