‘Out of the Shadow’: the love of a former Archbishop for his son

Features

Archives Researcher Adrian Gibb tells us about the tragic death of Paul Wand, son of the third Archbishop of Brisbane, The Most Rev’d Dr William Wand, and how he has been memorialised in our Diocese

On 5 September 1934, John ‘William’ Charles Wand became the third Archbishop of Brisbane in a lavish enthronement ceremony at St John’s Cathedral. Only 15 days later on 20 September, this same man received a cable telling him, his wife Amy and daughter Kathleen, that their son and brother Paul had ‘undoubtedly perished’ in a climbing accident in the Swiss Alps – a fact that was confirmed shortly thereafter. Archbishop Wand’s grief and his desire to memorialise the son he adored remain evident in our Diocese today – all one has to do is visit the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, next to Old Bishopsbourne, on the grounds of St Francis Theological College.

Advertisement

Paul Wand and his friend John Hoyland were friends from Oxford University. At this time British mountaineers were considered among the best in the West, and both students revelled in the mountaineering club at their prestigious university. The two friends were slowly building up a reputation in this field. John Hoyland, the nephew of famous Everest veteran and missionary surgeon Howard Somervell, was becoming increasingly renowned for his mountaineering skills. While it seems Paul Wand harboured ambitions to summit the largest mountains in the world. It was their joint ambition to reach the top of Mont Blanc, 4810 metres in height, on the Swiss/Italian border that led to their tragic and premature deaths.

Photograph used in the tribute article Archbishop Wand wrote about his son in The Courier Mail on 6 October 1934 (Image courtesy of the ACSQ Records and Archives Centre)

Mont Blanc is not an easy mountain to summit. Indeed, in 2017 alone 14 people died attempting the ascent. In 1934, with a lack of safety equipment that is available today, the prospect was even more fraught with danger. Perhaps that is what appealed to the young climbers. Paul Wand was 23 and John Hoyland was 19 when they set off to the Swiss/Italian border to attempt to scale the highest of the Alps. They made it to the Gamba Hut, on the Italian side of the great range, a refuge that many stayed in to rest before moving on to tackle the great southern wall of Mont Blanc. There they stayed overnight. The guardian of the hut recalled them being exhausted and having far too much equipment and supplies than he would have recommended. Yet, on 23 August 1934, at 9 am according to the guardian, they set out, overly burdened, in bad weather, inexperienced in the local conditions, and still tired from their previous day’s climbing. That was the last time they were seen alive.

An announcement in the Brisbane Telegraph that Paul Wand was missing, 20 September 1934 (TROVE image)

It was a month before their bodies were found. In late September four Italian guides and British mountaineer Frank Smythe, who would later write about the search, set off and caught sight of an abandoned ice axe. They discovered a deep crevasse, and after climbing down at great personal risk, found the bodies of the two young Englishmen. On one of the bodies was a watch that had stopped at 3.52 pm. So, after almost seven hours of climbing, they had fallen to their deaths, a drop that was estimated at being some 600 feet. Their bodies were brought down the mountain and, around the 26 September 1934, Hoyland’s father, a family friend of the Wands, and others attended a burial service for them at Courmayeur, in northwest Italy at the foot of Mont Blanc. It was reported that the whole village attended the moving funeral, with children placing flowers and a local clergyman conducting the service.

Announcement that Paul Wand’s body has been found, The Courier Mail, 24 September 1934 (TROVE image)

Before the bodies were found, Archbishop Wand was holding on to whatever hope he had that somehow his son had survived. On 19 September, before any final word had come in, the Brisbane branch of the Royal Society of St George was to have held a welcome address to the new Metropolitan. Upon hearing of the disappearance of Paul Wand, they contacted the Diocesan offices and offered to cancel the event. Archbishop Wand said he would still make it if the branch members wished it. However, the Royal Society of St George event organisers decided to postpone the event and moved a motion expressing sympathy to Archbishop Wand, his wife Amy, and their daughter, Kathleen, and the hope that somehow Paul would be found. Sadly, it wasn’t to be, and only a few days later they received official word that Paul and his young companion had perished and were being buried nearby.

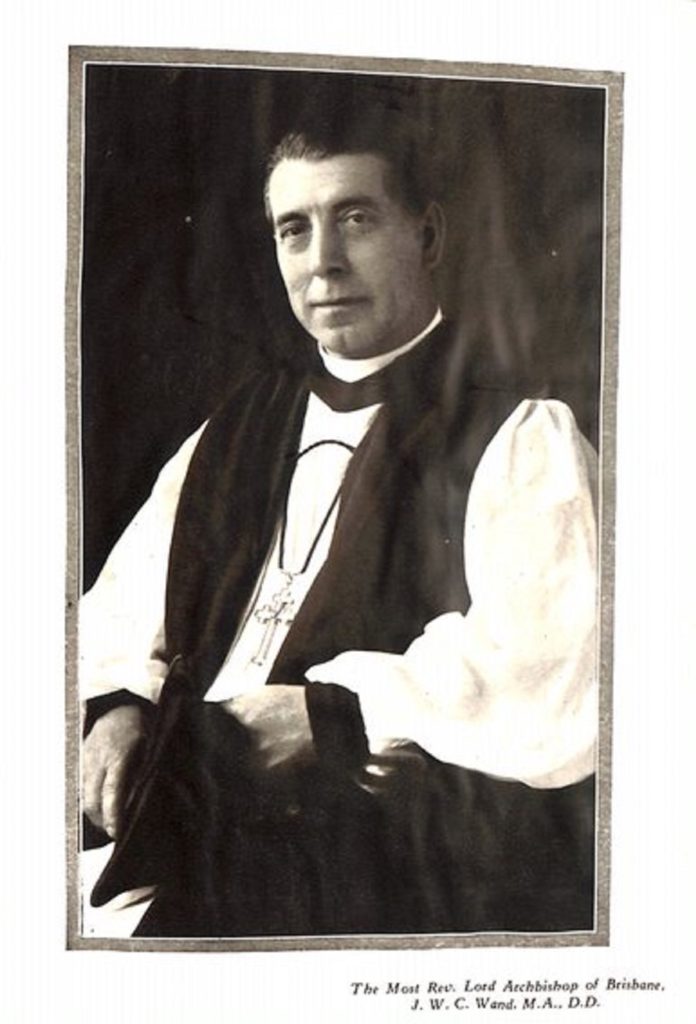

An official image of William Wand as Archbishop of Brisbane 1934 (Image courtesy of the ACSQ Records and Archives Centre)

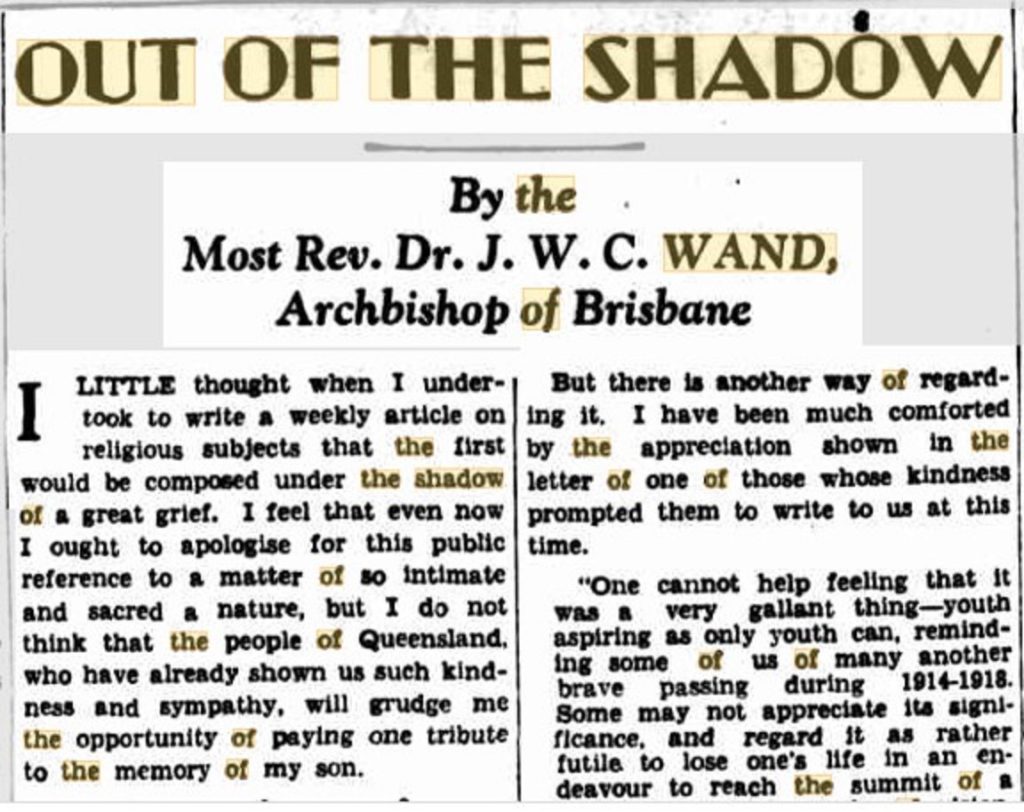

Upon arriving in Brisbane, The Courier Mail asked Archbishop Wand if he would be willing to contribute a weekly article on religious subjects to the newspaper. On 6 October 1934, he penned an article called ‘Out of the Shadow’, where he unburdened himself of some of the grief he was obviously struggling with. It is a poignant, inspiring, and heart-breaking reflection by a man who obviously and devotedly loved his son. He spoke of his son being his best friend, of their dream of writing together, of his admiration for his son’s compassion and understanding, and, finally, of how his faith was helping him through his pain:

Advertisement

“And then there is always the certainty of meeting him again. He was very proud of us – it is our proudest recollection now, and we must do our best to live up to it. We cannot let him down. When we see him again we must be the kind of people he thought he knew, and we must have done the work he expected us to. This is our ray of light in the present darkness. When the full brightness comes we shall see him in it. God grant that we may be worthy of him then.”

An excerpt from the article in The Courier Mail by Archbishop Wand that speaks of his grief at losing his son, written less than two weeks after the bodies had been discovered (TROVE image)

Four years later, Archbishop Wand and his family decided they wanted a more permanent memorial to their son’s memory in the Diocese that they had made their home, albeit temporarily. A year earlier, in 1937, St Francis Theological College had moved from Nundah to the grounds of the Archbishop’s residence of Bishopsbourne, Milton. The chapel on the grounds then became the College chapel, as well as the Archbishop’s. The Wand family asked famed Queensland artist William Bustard to create a triptych, a painting on three panels, to be placed above the altar of the chapel. The centre panel is the nativity scene, comprising Mary, Joseph, the baby Jesus, and adoring shepherds. At the rear of the panel, to the left, is a shepherd with no headwear, and the face of Paul Wand.

Close-up image of Paul Wand as a shepherd at the rear of the triptych in The Chapel of the Holy Spirit, St Francis College (Image courtesy of Eve James, Library Manager, Roscoe Library, St Francis College)

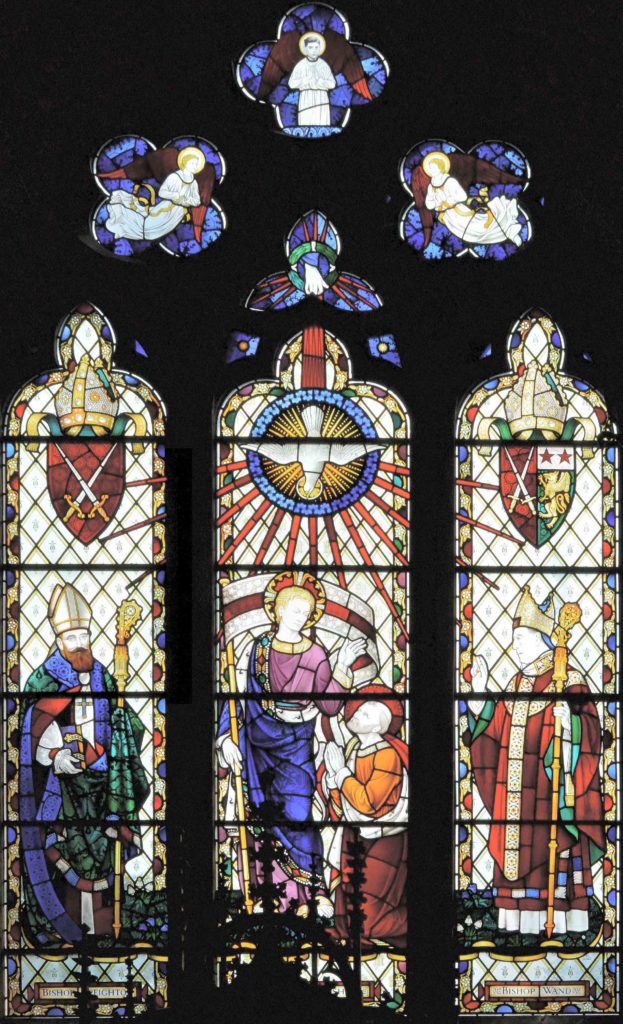

After leaving Brisbane to return to the UK in 1943, Archbishop Wand eventually became the Bishop of London in 1945, serving there for a decade during post-war reconstruction. One of the things that needed attention was the damage done to the chapel at Fulham Palace, the historical home of the Bishops of London. It is not surprising that here, too, in 1952, Bishop Wand commissioned a stained-glass window for the eastern side of the chapel that depicted, at its apex, this time as an angel, another image of Paul Wand.

The Eastern Window of the Tait Chapel in Fulham Palace, featuring Paul Wand at the top of the window, depicted as an angel ((This picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence)

A 1952 stained-glass window sketch by Sir John Ninian Comper of Paul Wand as an angel held in the collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects (Image courtesy of Architecture.com)

The images of Paul Wand at Fulham Palace and in the Chapel of the Holy Spirit at St Francis College, serve two distinct and profound purposes. Firstly, they serve as a tangible connection to one of our Archbishops, a thread through history, from now to 1934, and to a new Metropolitan finding his feet in the midst of tragedy. Secondly, and most poignantly, Paul Wand’s image serves as a signpost beyond titles and palaces. It is a signpost that clearly communicates the love of a father for his son.