Let's talk about racism: five people, five stories

Features

Racism and cultural prejudice have been increasingly discussed in the media and among the broader community recently. In this year of ‘Being Together: Practising Peacemaking’, five men and women of faith share about their personal encounters with racism and cultural prejudice in a range of settings

Racism and cultural prejudice have been increasingly discussed in the media and among the broader community recently. In this year of ‘Being Together: Practising Peacemaking’, five men and women of faith share about their personal experiences of racism and cultural prejudice, or of witnessing racism, in a range of settings. Their unique stories tell us that racism is real and that we all have a role to play in ‘practising peacemaking’ when we encounter racism and cultural prejudice.

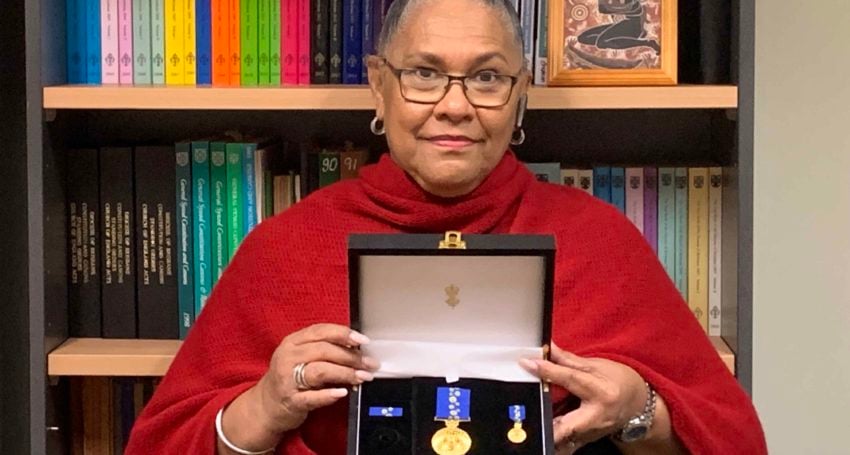

Racism in the workplace – Sandra King OAM, ACSQ Reconciliation Action Plan Coordinator, businesswoman and mother

Recently, the ABC reported that, “A Hunter Valley high school is under fire for not suspending a teacher who allegedly made racist comments about Indigenous Australians to a classroom full of students.” Even though there were a number of Aboriginal students reportedly present, I was not surprised that the teacher did not get suspended, as, in my experience, racist complaints by First Nation Peoples tend to favour the non-Indigenous worker.

Advertisement

Over 10 years ago, I was working for a high school and the following incidents led to my resignation.

A colleague told me that another staff member had seen my BMW parked outside and asked her, ‘Who has the Beamer?’ She said she replied with, “The ATSI Teacher Aide’ and he responded laughing, “Did she steal it?” To my horror, my colleague had laughed and ‘corrected him’ by saying, “No! She married a rich Greek guy!” I initially stood in total disbelief and then I was fuming. I angrily replied, “What? We started with nothing. My husband Jim had a second job and I was working part-time in a factory! We did it hard to have what we have now. That’s just a totally insulting comment.”

Not long after, during a lunch break with my co-workers, one arrived back from a department store with a new kitchen appliance. We all admired it. However, seeing where it was manufactured, I commented “Oh, it was made in France.” My colleagues looked surprised and asked what was wrong with that. I replied politely, “I stopped buying products that are made in France, including perfume and fashion in the early 80s. This is just my personal protest of their nuclear bomb testing in the Pacific Ocean.” One of the colleagues asked in a surprised tone, “Do you have morals?” The other ladies laughed until they saw the look of shock on my face. The colleague turned to me and said, “Oh, I’m sorry, didn’t mean anything by it, but I thought that you being Aboriginal, you wouldn’t have morals or principles!”

I was conflicted on whether I should stay, as I so loved working with my Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, but unbelievably offended and hurt, I resigned.

“I was born in Melbourne to Thai immigrants and grew up in Bangkok. We came back to Australia when I was 15. Whilst I have never experienced racism in the form of physical violence or the threat of it, I am no stranger to ‘casual’ racism, including right here in Brisbane” (Peter Branjerdporn)

Racism in casual conversations – Peter Branjerdporn, ACSQ Justice Unit staff member and pharmacist

I was born in Melbourne to Thai immigrants and grew up in Bangkok. We came back to Australia when I was 15. Whilst I have never experienced racism in the form of physical violence or the threat of it, I am no stranger to ‘casual’ racism, including right here in Brisbane. I was automatically lumped in with a group called the ‘Chinese Students’, along with any other students from Asia, at high school and university. Without my church and evangelical student friends, I probably would have felt a lot less supported and much more alienated.

Advertisement

A few years ago, an older colleague at a former workplace started ranting about “Asian students coming here to study and never returning home” and “taking our jobs” all morning. In order to make a point without being confrontational, I drily commented that we want their money to fund our universities, but don’t they dare make a life for themselves here. Getting the drift, my colleague replied, “Oh, but not you – you’re an Aussie to me. You’re one of us.” I was stunned and so angry that I had to leave work early that day.

Even though my colleague texted later that day to apologise, I never explained to him why I was offended. In hindsight, I should have tried explaining in a loving way how racism toward people of colour, especially those of Asian heritage, is also racism toward me. Racism affects all of us because we are all brothers and sisters in God’s family.

I realise now that the insecure nature of my colleague’s work, along with his fear of losing his job to a younger generation of professionals in multi-cultural Australia, likely fueled his racism.

We all need to confront our own fears and challenge our assumptions about people from other cultural backgrounds so all people feel safe and welcome.

“The racism I experience tends to be intertwined with chauvinism. If a racist white male sees a female Muslim, he often feels that he has the right to say and do whatever he wants to her. But if a Muslim male is with me, I do not experience such encounters. This is really awful because it’s another way of making me feel disempowered” (Salam El-merebi)

Racism in big cities – Salam El-merebi, social worker, art psychotherapist, human rights advocate and mother

I am a visible Muslim woman who wears a head scarf and I have experienced a lot of discrimination and racism as a result. No witness has ever come to intervene. Bystanders just stand there watching or acting as if they did not see anything.

A few years ago I was assaulted physically by a young white man, who also made racist slurs to me about my head scarf. This happened in daylight hours on a suburban street on Brisbane’s south side. Other men and women watched, but nobody came to my aid.

It’s common for this kind of thing to happen to Muslim women when they are either alone or with other Muslim women. This kind of thing never happens when I am with my husband.

The last incident happened at a local Bunnings when I was five months pregnant with my baby son. This time my husband was with me; however, he was a bit further from me, so it looked as though I was alone. A white 35- to 40-year-old man walked passed me and said in an aggressive tone, “There are a lot of you bloody mozzies.” In response, I said, “Excuse me, did you just say what I heard?” And he replied, “Well there is a lot of you.” I normally just deal with it and stand up for myself, but this time I asked my husband to step in. The guy freaked out and could not handle the fact that there was a male with me. My husband got the Bunnings manager involved and made such a scene that around five horrified families came to us to say, “We are not all racist.” We also had an Aboriginal man come up to my husband in a spirit of solidarity and say, “Thank you brother. Good on you.”

Thus, the racism I experience tends to be intertwined with chauvinism. If a racist white male sees a female Muslim, he often feels that he has the right to say and do whatever he wants to her. But if a Muslim male is with me, I do not experience such encounters. This is really awful because it’s another way of making me feel disempowered. I can take care of myself and I should not need a Muslim male, like my husband, with me to be safe.

“While these days I am determined to do more when I witness such acts of racism, there are days when I am not brave enough, or I’m in a hurry, or I tell myself “It’s not that bad”…and then I remember Syd and all the stories I’ve heard from other First Nations people since and I‘m motivated to do better,” (Bishop Jeremy Greaves)

Racism in small towns – The Right Rev’d Jeremy Greaves, Bishop and father

Sometimes ‘casual’ or unconscious racism can be the most insidious.

I vividly remember arriving in a small town, which not long before had been proclaimed “Australia’s most racist town” by a major metropolitan newspaper, to begin work as parish priest. I was keen to make a good impression and not make too many waves. I arrived full of idealism, energy and passion.

“Just wait ‘till you’ve had to put up with them for a while,” I was told at dinner a few days after we’d settled in. Then, “Don’t let the darkies get at your orange tree,” advised a neighbour. In both instances no one flinched, and I didn’t want to make a fuss by saying anything.

The following week I walked into one of the local shops. When I arrived, there were already four people waiting at the counter, so I hung back prepared to wait. The person behind the counter looked straight through the four Aboriginal women already waiting and asked me what I wanted to order. I remembered my friend Syd Graham, a Kaurna man, who was ordained priest alongside me, who made a point of wearing his clergy shirt and collar whenever he went shopping because “for the first time in my life, I don’t get served last.”

I motioned towards the women ahead of me in the shop and said, “I think these women were next.” The shop attendant tutted and raised her eyebrows in disdain and then made a show of spraying air-freshener around behind the counter before demanding of the women, “Whadda ya want!?”

I felt ashamed and embarrassed and could feel my cheeks reddening as I stood in silence. I paid for my drink and left.

I still feel shamed by that encounter, and while these days I am determined to do more when I witness such acts of racism, there are days when I am not brave enough, or I’m in a hurry, or I tell myself “It’s not that bad”…and then I remember Syd and all the stories I’ve heard from other First Nations people since and I‘m motivated to do better.

“One of the most disturbing incidents happened three years ago. My son – who’d just started at a school – asked me what ‘nigger’ meant. I was shocked! I asked where he heard it and he said innocently, ‘My friends at school call me that.’ ” (Anglicare SQ staff member)

Racism in schools – Anglicare Southern Queensland staff member and mother

I was born in Rwanda and I have called Australia home since 2003. Coming from a country with a colonial past, the seeds of hate and division were not new concepts to me. I survived genocide and came to Australia as a refugee.

During my first few years in Australia, I generally felt welcomed and included, but there were occasions where unpleasant remarks or glances were made. For example, there were times I felt that my rental applications were unfairly denied.

One of the most disturbing incidents happened three years ago. My son – who’d just started at a school – asked me what ‘nigger’ meant. I was shocked! I asked where he heard it and he said innocently, “My friends at school call me that.” I was outraged!

As a parent, your first instinct is always to protect your child. I told him that those children were using a bad word and that he needed to tell them his name. I told him about the strength of his Biblical name. I also told him that if it happens again, he needed to tell his teacher immediately. I thought about changing schools but soon realised that it was no guarantee from a similar incident occurring. I decided to talk to his teacher and luckily she listened and took action. I also increased my involvement in the school and thankfully, I did not hear such revolting racist slurs again.

When we moved house, my son changed schools and has now made better friends. Unfortunately, he still gets picked on by a few for being different, and it breaks my heart. But I am now confident that he has built resilience to handle such tricky situations. I also have good lines of communication with his school. I can only hope and pray that the next generation will not inherit such past racist bigotry and hatred.

We all need to stand against racist language and ideologies within our circle of friends and relatives and workplaces and the wider community. Only then will we create a more harmonious world to live in for all of our children.

Australian Human Rights Commission

The Australian Human Rights Commission website says that:

“Many people want to stand against racism but aren’t sure how. We’ve all been a bystander at one time or another. It can be uncomfortable. Often people don’t respond because they don’t want to be a target of abuse themselves. Standing up to racism can be a powerful sign of support. It can also make the perpetrator think twice about their actions. When responding, always assess the situation and never put yourself at risk. Your actions don’t need to involve confrontation.”

Visit the Australian Human Rights Commission website for suggestions on how to address racism in public, online, in the workplace and in education settings.