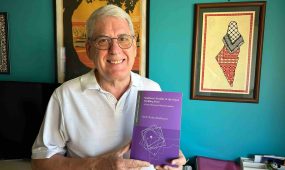

Christians and Muslims can be Friends

Books & Guides

“In writing this book, Father Dave seeks to offer information to correct misconceptions about Muslims based on his own experience and his theological and doctrinal perspective. He contends that through addressing the unwarranted negative perceptions of Muslims, the Church is well positioned to have a positive impact on attitudinal change that could influence local and international events,” says Dr Robin Ray from Anglican Overseas Aid

Based on his own experiences and discussions with Muslims and Christians, Anglican priest Father Dave Smith constructs a strong case for positive relationships between Muslims and Christians. He makes a clear distinction between systems of belief and the people who interpret those beliefs:

“Our religions are not at war and our holy books are not a war” (p.14).

“Conflict between Christians and Muslims has nothing to do with religion” (p.38).

In short people are the problem.

The book is presented in two parts. In the first, Father Dave shares his views and experience using doctrinal and Biblical bases for discussion of the issues that underpin perspectives and often misinformed beliefs about Muslims. The second part contains transcripts of interviews with Muslims and Christians discussing various aspects of Muslim-Christian relationships and possible strategies for facilitating mutual understanding and friendship.

Father Dave suggests that the basis of some Muslims’ antagonism towards those outside Islam is more political than religious, arising from foreign government support for Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and the killing of innocent people in wars. It’s the only thing that unites the sectarian and national divisions of the Muslim world:

“…the US and her allies maintain the Palestinian Occupation…the treatment of the Palestinian people by the State of Israel…grieves the heart of God” (p.41).

Often for non-Muslims, general ignorance and misinformation about Muslims promulgated in the wider community breeds fear, suspicion, mistrust and animosity:

“…we refuse to listen to their side of the story, we inevitably see their violence as irrational and write these people off as “pure evil” (quote of one Australian Prime Minister)” (p.43).

Advertisement

In writing this book, Father Dave seeks to offer information to correct misconceptions about Muslims based on his own experience and his theological and doctrinal perspective. He contends that through addressing the unwarranted negative perceptions of Muslims, the Church is well positioned to have a positive impact on attitudinal change that could influence local and international events.

Across eight chapters, Smith clearly addresses issues, such as ‘Christianity and Islam are not at war’; ‘Do Christians and Muslims worship the same God?’; ‘So why the jihad?’; ‘Removing the plank’; and, ‘Who is my brother?’. Three key concepts that are critical to the messages in this book are dogmas of faith, recognising the humanity of our adversaries and cleaning up the swamp.

One method Smith effectively uses to improve or clarify the reader’s knowledge and understanding of their own and the Islamic faith is to describe several dogmas inherent in Christianity and their parallel dogmas in Islam. He begins with God, suggesting that it is unhelpful to ask if we worship the same God when both are monotheistic faiths. For Muslims, the revelation of God is found in Torah and Qur’an which is absolute and infallible. However, “Christianity is less about the book and more about the person” (p.30). For the Christian, God as found in the scriptures is important, but God is revealed though Jesus the Christ, the word made flesh, with the Father and Son one. In Islam, God does not share His divine nature. Instead “Muslims consider Jesus to be very Godly” and Muhammad as a messenger of God (p.28).

Advertisement

Having considered the perception of God, Smith moves on to use these understandings to describe our respective relationships with God with regard to obedience and forgiveness. In Islam, “If you do the right thing by God, you get closer to God. If you do the wrong thing by God, you get further away from God” (Sheikh Mansour, p.33). The concept of forgiveness that Christians find in Jesus, “shifts the foundation of Christian religion away from one focused on law and obedience to one that is primarily about love and grace” (p.32) leading to a closer relationship with God in which obedience is a natural behaviour. Having said that, Father Dave also points out that he has experienced more love and grace among Muslim groups than among some Christians. A salient point that should cause Christians to pause and reflect on their behaviour.

The second concept that brought me up short was Smith’s focus on the need to recognise the humanity in our adversaries and see our interfaith relationships from another point of view. He cites not only recent theatres of war that have been sold to us as ways to control the perceived violence of Islam, and also other reinforcing factors such as good and evil plots and archetypes in the books and films we consume. Given that many innocent civilians, including children, have been killed by Australian and American forces, Smith explains the tribal culture of vengeance which makes one duty bound to avenge death in your family (p.40) as a contributor to jihadist activity. Media images of soldiers dehumanising Muslims is bound to anger other Muslims. Would we not feel similarly if this dehumanisation and violence was happening to our people? This section of the book brings humanity to the front of our awareness, something that is often missing in mainstream media portrayal of conflict situations. Smith also encourages us to “…understand our foreign policy and see what it looks like from the other side” (p. 40), that is, to stop and examine the plank in our own eye (Matthew 7.3-5).

As a way forward, Smith skilfully uses the analogy of a swamp as a breeding ground for the mosquitoes that cause malaria. Cleaning up this swamp requires action by both Muslims and Christians. “The Bible and Qur’an contain significant amounts of potentially inflammatory material, depending on how it is interpreted”(p.11). Also “Syrians are under no illusions as to who is to blame for their misery… they know too that these people… are being funded and support by foreign governments including our own” (p.49). Father Dave rightly points out that just as killing mosquitoes does not stop malaria, killing terrorists will not stop terrorism breeding. Instead he provides seven points ranging from apologies to removing sanctions and withdrawing American troops, as a beginning to cleaning up the swamps that breed terrorism (p.51).

The text of the book itself is easy to read. Father Dave’s arguments are logically ordered and presented in a manner that encourages contemplation of the issues. Use of personal stories, both from his own perspective and others, engages the reader. Interview transcripts bring stories alive, but this section could be tiring to read in one sitting.

I recommend the book as a useful resource for discussion in parishes and social groups. However, Smith warns not to “paper over” doctrinal differences that are “deep and profound”, but to engage meaningfully with Muslims. He emphasises the need to accept the differences and appreciate another’s perspective, learn from each other, share a meal – certainly my favourite way to build relationships.

Dave Smith, 2020. Christians and Muslims can be Friends. Rethink Press Limited, UK.