The night the Zeppelin bombs fell

Features

“The Vicar’s wife and the Sunday School teachers should have been meeting in the Parish Room, but the meeting was serendipitously moved to the Parsonage, where they could have coffee afterwards. Plans altered, for no particular reason. While the Parish Room was destroyed in the bombing, tears of joy and relief came later,” says Frances Thompson in her retelling of her great-grandfather’s real-life account

The old retired Vicar sat in his chair, remembering the cold nights of the Great War when he wore two overcoats, and the evening when 23 bombs fell and one landed on his church. He can still hear the humming of the horrid Zeppelin overhead and bring to mind the acrid smell from the fires. His young granddaughters often ask him questions about the War.

In January 1916 he had recently returned from a visit to Plymouth, where he went to embark his six-year-old son on his first term at prep school. His wife cried, but the boy settled down quickly, with the Headmaster, his brother, declaring the boy to be “a fine lad”.

The Vicar was situated at St Bartholomew’s in the village of Hallam Fields, for 47 years, not so far from Derby. A poor area, largely ironworkers and farmhands and no one of his class at all, save perhaps the doctor.

There had been widespread indifference among the population of Hallam Fields – many did not seem to realise the seriousness of war. The man had preached a sermon, saying people “wanted waking up”, they would not realise the consequences of war until a few bombs fell nearby. People wished the war to be over merely because things cost a little more in the shops.

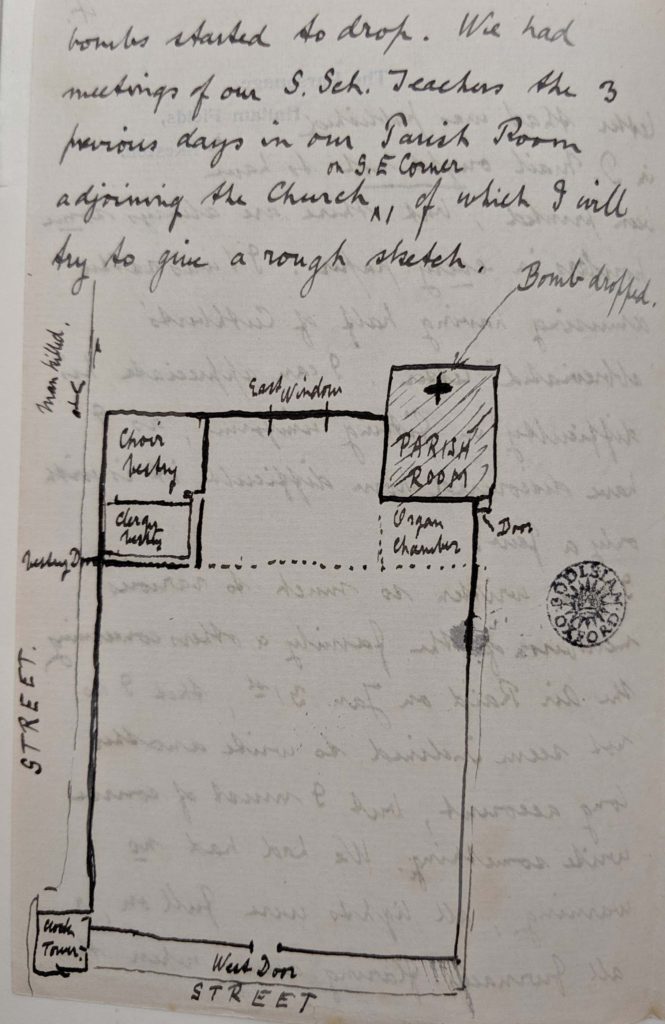

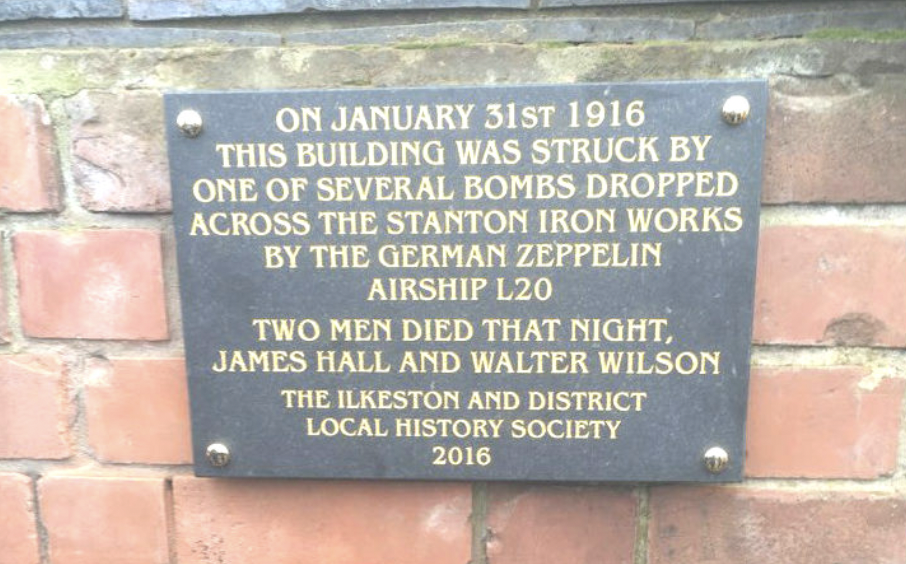

He sat in his chair and remembered that night. 31 January 1916 was a Monday. There were no warnings, no sirens howled. The furnaces at the Stanton Ironworks flared away, so Hallam Fields would have been an easy target, visible in the night sky like a roman candle. The man’s wife was at a meeting at the Parsonage, next door to the church. There was a visiting speaker and 20 to 30 Sunday School teachers present. The man was supervising drill with the Church Lads’ Brigade at the school, just down the lane, next to the ironworks.

Advertisement

The first bomb fell at about 8.30pm; the Brigade had finished drill and the man was about to join the meeting at the Parsonage. It shattered the big windows on the East side of the school, next to the ironworks. He thought it was an explosion at the works, but then two more bombs dropped – he saw the flash and realised what it actually was. The Zepp was humming overhead. He put out the lights and the man and boys huddled in what he determined to be the strongest part of the school, the passageway, clear of the windows. More bombs fell, this time further away. They ventured outside to see if the coast was clear.

“The Rev’d Edmund Machell Cox’s sketch from his Budget letter, March 1916, marking the location of the bombing damage done to St Bartholomew’s Anglican Church in the village of Hallam Fields”

The dirigible blimp was circling round before coming back again. The Vicar hastily called the boys back inside and shut the door. Three more bombs fell and the windows at the end of the passage shattered. The airship seemed to drop all of their bombs in strategic threes.

Then the Zepp went further away, and he told the boys to run home, whilst he hurried back to the Parsonage. But suddenly it was right overhead again and three more bombs fell; one fell into the railway cutting, about 30 yards away. A piece of the railway line flew up and hit the school door, which the man had just locked. It broke the door in, and parts of the roof fell, just where the man and boys had been sheltering. Opposite the church, the shop windows were broken.

Advertisement

Everyone was glad to see him at the Parsonage. His wife had managed very well with the Sunday School teachers – some had screamed and fainted. The noise and shock had, of course, been traumatic, but nothing was broken.

The man later discovered that a bomb had fallen on the roof of the Parish Room and exploded, wrecking it completely. The church walls did not suffer much on account of their thickness. All the stone tracery of the beautiful East window was destroyed, as well as the lovely stained glass. The clock dials in the Clock Tower were shattered and all the church windows were broken.

He was not able to take any photographs for the next few days, as his camera would have been confiscated by the Home Guard. But when the coast was clear, he managed to quickly take a few snaps.

“Photo taken by The Rev’d Edmund Machell Cox in1916 showing the wreckage of the Parish Room of St Bartholomew’s, Hallam Fields”

Over £50 was raised for the Restoration Fund by selling photographs of the destroyed East window for three pence each, as well as selling the snaps which the man had taken. The community pulled together and raised money for the church, during a time of extreme hardship. The organ had to be taken apart for cleaning and repair; the village also raised funds for that. The Bishop came and there was much celebration and rejoicing when the new East window was eventually completed after the War.

Related Story

Features

Features

Three Anglican priests, 10 siblings, a dog named ‘Satan’ and hundreds of letters

The man recalled how only two men were killed on the night of 31 January when the bombs fell. Miraculously, no one else was injured. One man was killed at the ironworks and the other was injured while passing the church on his way home, later dying in hospital. If the man had let the boys run off from the school earlier, some of them would also have been injured, or worse, when the bomb fell on the church.

In 1916 the Vicar was thankful that no young men had perished whilst fighting for ‘King and Country’. He knew them all from the Church Lads’ Brigade. Despite fear, there was still hope for the future – hope that the war would soon end. Alas, that optimism was short-lived. The war memorial was constructed next to the churchyard, a place to remember the 26 young men from the village who died, a place for the families to grieve. He could name them all.

Annie May, (the Vicar’s wife) and the Sunday School teachers should have been meeting in the Parish Room, but the meeting was serendipitously moved to the Parsonage, where they could have coffee afterwards. Plans altered, for no particular reason. While the Parish Room was destroyed in the bombing, tears of joy and relief came later.

Author’s note: This is my retelling of The Rev’d Edmund Machell Cox’s account of the bombing of his village, including his church, by a German Zeppelin airship on 31 January 1916. All historical details are accurate. He is my great-grandfather, and stayed at the same Anglican church in Derbyshire for his whole working life. The Bishop had quite a job to persuade him to retire.

“This plaque was installed on the wall of the St Bartholomew’s, Hallam Fields church building in 2016 by the Ilkeston History Society, commemorating 100 years after the Zeppelin bombs fell; the church building still exists on the corner of Crompton Road and Hallam Fields Road in Derbyshire, UK”