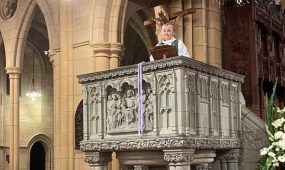

“A blind obsession with love”: 2021 Valedictory Service sermon

Homilies & Addresses

“…a blind obsession with love requires us to build relationships not walls, requires trust not fear, requires that we make room for difference rather than cling to an arrogant assurance that my way is the only way,” says Bishop Jeremy Greaves

In a recent sermon, a friend of mine, Fr Grant Bullen, told the story of Aristoclis Spyrou who was elected Patriarch of Constantinople in 1948 and given the name Athenagoras.

Athenagoras had that wonderful (and rare) combination of deep faithfulness to the Gospel and great managerial skill, which enabled him to lead his church out of its inward-looking and closed mentality towards an openness to the world.

He was a tireless champion for unity – in the world, as well as in the Christian Church – and in a huge moment in 1964, he joined with Pope Paul VI, in mutually lifting (nullifying) the anathemas the Churches of East and West had pronounced on each other…nearly a thousand years earlier in 1054.

In ecclesial terms, an anathema, is a formal and legal rejection of “the other”.

An anathema is even more radical than excommunication: an anathema dismisses the other as a heretic (not a true Christian), and breaks off any relationship and conversation…until the other person repents and comes over to your righteous position.

An anathema says, “You are no longer one of us!”

At the time, there were many in the Orthodox Church that attacked and condemned Athenagoras for his decision to lift the ancient anathema. Amongst other things, he was accused of “sacrificing Orthodoxy to a blind obsession with love.”

“…a blind obsession with love”…if only more of the Church could be accused of that!!

In response Athenagoras said:

“I do not deny there are differences between the Churches, but I say we must change our way of approaching them. For centuries there have been conversations between theologians, and they have done nothing except harden their positions. I have a whole library about it. And why? Because they spoke in fear and distrust of one another, with the desire to defend themselves and defeat the other. Theology was no longer a pure celebration of the mystery of God. It became a weapon. God himself became a weapon.”

Advertisement

It is a deep sadness that throughout the history of the Church, fear and distrust have become intolerance and hatred and again and again the Gospel of love – the pure celebration of the mystery of God – is distorted and weaponised and we turn God and the scriptures into our excuse for excluding and ostracising those whose difference unsettles or scares us…those whose difference challenges how we want things to be.

Athenagoras said there was a different way (his words continue):

“I am trying to change the spiritual atmosphere. The restoration of mutual love will enable us to see the questions in a totally different light…Only by love can we glorify the God of love…”

In the Gospel story we’ve just heard, Bartimaeus calls from the margins – that place of exclusion and ostracism reserved for those who are different or unacceptable, those who unsettle or scare us…

And, Jesus notices this man calling from the margins and ironically asks Bartimaeus the same question he asked James and John. When their minds were desperately focussed on shoring up their place amongst the “insiders”… Jesus asks, “What do you want me to do for you?”

Advertisement

And, Bartimaeus not only knows what to ask for, it seems that he also understands more fully who Jesus is, than any of the disciples.

There’s something else striking about this story…

When Jesus restores Bartimaeus’ sight, when he heals this beggar formerly consigned to sitting by the side of the road, on the margins of all that went on around him…Jesus tells him, “go on your way.”

Ironically, Bartimaeus’ response is not to “go” but to “follow,” an interesting contrast to Jesus’ invitation earlier in the same chapter to the rich man, to “come, follow me.”

One man, the rich one, is explicitly invited to let go of what holds him back, and to follow Jesus, but he declines, with great sadness. The other man, poor but in a deeper sense, spiritually rich, is freed from what holds him down or keeps him out, and is told to “go” – he decides, presumably with great joy and gratitude, to “come, follow” Jesus.

An interesting contrast in invitation and acceptance!

When Bartimaeus regains his physical eyesight, he is free to follow Jesus, and he follows him on the way, no longer excluded, shut out, labelled as other…no longer sitting alone by the side of the road, but traveling on it with a band of companions.

A man from the margins, separated from the community, alone and in poverty is invited in. He’s not asked to sign up to a creed or a great list of doctrines or dogma, he’s healed and invited in.

New Testament scholar Stephen Patterson (2018) has recently argued that the first Christian creed was not a proclamation of separation from others (believers from non-believers)…the sort of thing that might be used as a weapon. Rather, he says, it was a declaration of human solidarity. That creed was part of the very first baptismal liturgies of the Early Church:

“For you are all children of God in the Spirit.

There is no Jew or Greek;

There is no slave or free;

There is no male and female.

For you are all one in the Spirit.” (Galatians 3.26-28)

He insists that Christianity was successful because it imparted a social vision of unity in a deeply divided world and called people to a new identity. He writes, “We human beings are naturally clannish and partisan: we are defined by who we are not. We are not them. This creed claims that there is no us, no them. We are all one. We are all children of God.”

Not only did the first Christians proclaim these words, they practised them in their communities. They developed habits of including others, of breaking down barriers, of eating with and befriending those they once found objectionable.

Diana Butler Bass says that, “For at least some time in the early years of Christianity’s existence, the faith was marked by its insistence of the common kinship of humankind – that we could indeed, be one. And there is evidence that they practiced what they preached.”

We know that there is a different way…and it is the Way of Christ. It is that way that offers healing and then embrace, even to those we would normally leave on the margins, banish to the outside.

And, its foundation, its heart, its very substance is love. Perhaps you could even call it, “a blind obsession with love”…as it’s “only by love that we can glorify the God of love.”

A commitment to this way will always be an antidote to our natural tendency, in our fear and distrust, to weaponise God…to turn God into an excuse for excluding and repudiating those whose difference scares us…those whose difference challenges how we want things to be…because a blind obsession with love requires us to build relationships not walls, requires trust not fear, requires that we make room for difference rather than cling to an arrogant assurance that my way is the only way.

A Church like this will never be just a community of the strong, or the wealthy, or the powerful, or the independent. But will be, as one writer puts it, “a community, of those who know their need and seek to be in relationship with each other because they have learned that by being in honest and open relationship with each other they are in relationship with God, the very one who created them for each other in the first place.

“This is what the Church was originally about – a place for all those who had been broken by life or rejected by the powerful and who came to experience the love of God through the crucified Jesus as the One who met them precisely in their vulnerability, not to make them impervious to harm but rather open to the brokenness and need of those around them.” (David Lose, 2015)

It’s fascinating that the very next story in Mark’s Gospel, after the story of Bartimaeus is that of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem.

If, after throwing off his cloak, he follows Jesus “on the way,” Bartimaeus walks immediately from his blindness into the Passion – the greatest of all acts of love that sits at the heart of our faith.

References

Oliver Clement, 1969, From Conversations with Patriarch Athenagoras 1886 – 1972. Excerpts found in ‘Remembering Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras’.

Stephen J. Patterson, 2018, The Forgotten Creed: Christianity’s Original Struggle against Bigotry, Slavery, and Sexism, Oxford University Press.

Diana Butler Bass, 2021, in How to Heal our Divides: A Practical Guide, independently published.

David Lose, 2015, ‘Pentecost 19 B: Communities of the broken and blessed’, blog post.