Aboriginal Tent Embassy: the world’s longest ongoing First Nations land rights vigil

Features

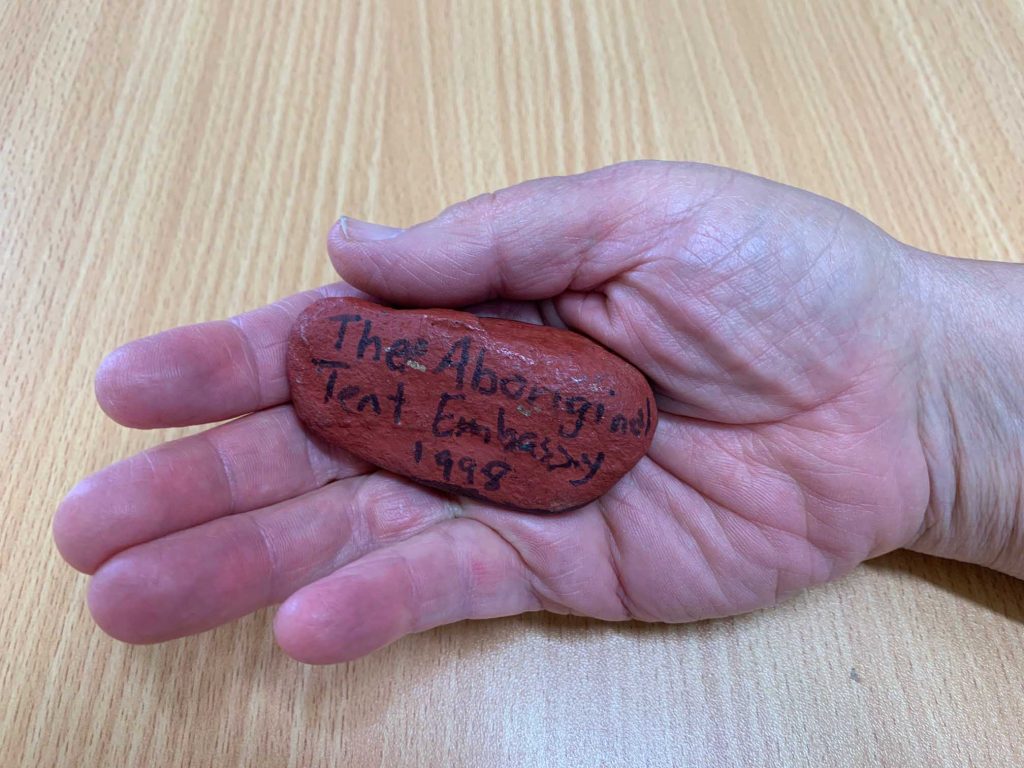

“Despite growing up in Canberra, I only first heard about the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1998 at the age of 22. During that year I was employed by an Aboriginal agency to tutor First Nations primary school children…At the end of the final tutoring session, the student’s parents thanked me with hand painted gifts, including a rock featuring the Aboriginal flag on one side and ‘The Aboriginal Tent Embassy 1998’ on the other,” says Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group member, Michelle McDonald

Please note: First Nations peoples should be aware that this content may contain images or names of deceased persons.

I grew up in Canberra between the late 1970s and early 1990s. The rights of First Nations peoples were not discussed in my home, school or among my peers. At school I was taught little about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures. I vividly remember school excursions to Old and current Parliament Houses, the High Court of Australia, Cockington Green Gardens, the National Carillion, Blundells Cottage, and so on. Trips to the nearby Aboriginal Tent Embassy were never included on excursion itineraries.

Despite growing up in Canberra, I only first heard about the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1998 at the age of 22. During that year I was employed by an Aboriginal agency to tutor First Nations primary school children. The parents of one of these children, a remarkably bright sixth grade girl, were actively engaged in the Aboriginal Tent Embassy vigil. They spoke of it often, so I gradually pieced together what the embassy was about, feeling beyond slightly awkward because of my ignorance. At the end of the final tutoring session, the student’s parents thanked me with hand painted gifts, including a rock featuring the Aboriginal flag on one side and “The Aboriginal Tent Embassy 1998” on the other. It sits on my work laptop right next to the start button, so it’s the first thing I see when I commence work each morning.

“At the end of my final tutoring session, the student’s parents thanked me with hand painted gifts, including a rock featuring the Aboriginal flag on one side and ‘The Aboriginal Tent Embassy 1998’ on the other. It sits on my work laptop right next to the start button, so it’s the first thing I see when I commence work each morning” (RAP Working Group member, Michelle McDonald)

January 26 this year marked the 50th anniversary of what is known today as the “Aboriginal Tent Embassy”. The embassy is considered the world’s longest ongoing First Nations land rights vigil.

The origins of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy hark back to an April 1971 Northern Territory Supreme Court judgement that ruled in favour of mining company Nabalco and the Commonwealth of Australia and against the Yolngu people. The case was about traditional Yirrkala land being sold to Nabalco without Yolngu consultation. In his 263-page judgement Justice Richard Blackburn decided against the Yolngu, ruling that:

“…the relationship between clan and land did not amount to proprietorship as that is understood in our law; and that the clans had not sustained the burden of proof that they were linked with the same land in 1788 as now; that no doctrine of common law ever required or now requires a British government to recognise land rights under Aboriginal law which may have existed prior to the 1788 occupation; that Aboriginal land rights in Australia were never expressly recognised; and that if the clans had had any rights they would have been effectually terminated by the mining (Gove Peninsula Nabalco Agreement) Ordinance 1968.” [Bolded text is author’s emphasis]

In May 1971, Yolngu representatives travelled to Canberra to see Prime Minister William McMahon, handing him a statement written in Gupapunyngu language. Translated into English, it reads:

“The people of Yirrkala have asked us to speak to you on their behalf. They are deeply shocked at the result of the recent Court case. We cannot be satisfied with anything less than ownership of the land. The land and law, the sacred places, songs, dances and language were given to our ancestors by spirits Djangkawu and Barama. We are worried that without the land future generations could not maintain our culture. We have the right to say to anybody not to come to our country. We gave permission for one mining company but we did not give away the land. The Australian law has said that the land is not ours. This is not so. It might be right legally but morally it’s wrong. The law must be changed. The place does not belong to white man. They only want it for the money they can make. They will destroy plants, animal life and the culture of the people.

The people of Yirrkala want:

- Title to our land.

- A direct share of all royalties paid by Nabalco.

- Royalties from all other businesses on the Aboriginal Reserves.

- No other industries to be started without consent of the Yirrkala Council.

- Land to be included in our title after mining is finished.

Signed R. Marika, Daymbalipu Mununggurr, W. Wunungmurra”

McMahon promised Mr Marika, Mr Mununggurr and Mr Wunungmurra that a new Ministerial Committee investigating First Nations matters would consider how to protect Crown reserve lands for community cultural and ceremonial use; how to provide the tenure needed to sustain commercial initiatives; and, how to purchase land for First Nations peoples.

However, the McMahon government announced on 25 January the following year that the Ministerial Committee had decided to reject Aboriginal title to land. Instead an application process for general purpose leases for up to 50 years was introduced. The leases excluded any mineral and forest rights and were only considered if applicants could demonstrate “intention and ability to make reasonable economic and social use of the land applied for.”

The day after hearing the statement on the radio, four young Koorie men, Michael Anderson, Bill Craigie, Bertie Williams and Tony Coorey, travelled from Redfern in Sydney to Canberra to protest the decision, with Mr Anderson telling the press that:

“The land was taken from us by force…We shouldn’t have to lease it…Our spiritual beliefs are connected with the land.”

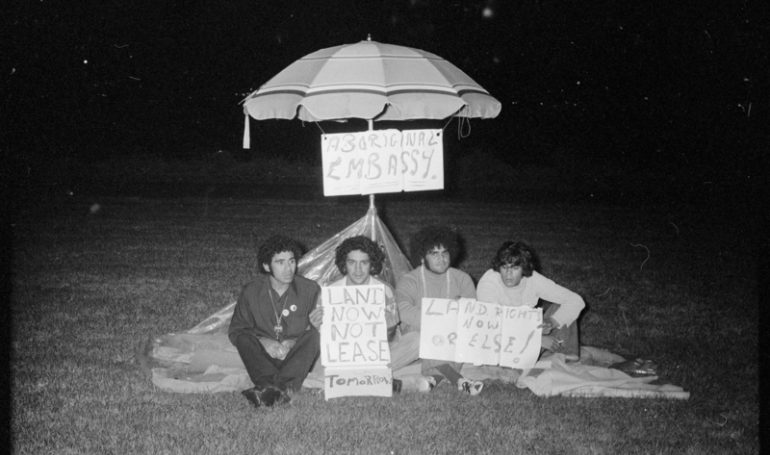

Viewing the statement, and its delivery on the eve of such a contested day, as an intentional provocation, the four men planted a beach umbrella on the lawns of (what is now Old) Parliament House. There they erected a hand-made sign, reading “Aboriginal Embassy”. In the words of Gumbaynggirr man Dr Gary Foley, they were being treated like “aliens in their own land”, hence why they deemed an embassy necessary. Embassy members also set up a mailbox, receiving international mail within three months.

They were widely supported by the media, which was critical of McMahon’s statement. Regarding McMahon’s claim that granting the Yirrkala people independent ownership of their land would set an uncertain precedent, The Australian reported on 26 January 1972:

“He [McMahon] means the question of precedent could bother some pastoralists, including overseas groups who have been leased enormous areas without a qualm. In fact, it has been pointed out repeatedly that the risks of such a precedent are infinitesimal when Yirrkala is in Crown reserve land and not on lease to anybody.”

The police were unable to move on or arrest the men because camping on the grounds of Parliament House was legal provided that there were less than 12 tents. By April 1972, the embassy grew to a reported eight tents, with many well-known First Nations community leaders and non-Indigenous people from across the country joining them. Diplomats from a number of countries, including Canada, also showed their support.

The McMahon government was humiliated by the embassy’s rapidly growing support and profile. So, in May 1972 the Minister for the Interior Ralph Hunt, who was openly opposed to Aboriginal land rights and a member of the Ministerial Committee that had rejected them, announced hastily-drawn up laws rendering it illegal to camp on unleased Australian Capital Territory (ACT) land.

The embassy was subsequently torn down by police twice – first on 20 July and then again on 23 July after it was re-erected. News of police violence spread across the country, leading to more support for the embassy. Later that month, the tents were peacefully re-erected and removed in a symbolic gesture in the presence of more than 2,000 supporters, with the matter to be considered in the ACT Supreme Court.

On 13 September, the ACT Supreme Court declared that the embassy’s removal was illegal. However, the removal ordinance was legally introduced soon after to prevent the embassy’s re-erection on the lawns of Parliament House. Despite this, it was re-established there again the following year.

It remained there until 13 February 1975 when Arrernte man Dr Charles Perkins AO negotiated its removal, pending the enactment of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) Act 1976.

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy stands on the lawns opposite Old Parliament House in Canberra today

The Yirrkala people eventually received title to their land in 1978 under the Act. However, the mining leases that they objected to were excluded from the Act’s provisions.

While the notion of terra nullius (or “nobody’s land”) that was used to justify the 1788 occupation was not contemplated in the Yirrkala case, it was later raised and recognised in the famous 1992 High Court Mabo case, which overturned Justice Blackburn’s reasoning.

Until 1992 the embassy was located at numerous places across Canberra, including the site of the current Parliament House. In 1992, to commemorate its 20th anniversary, the embassy was relocated to the Old Parliament House lawns, where it remains today.

It was listed on the Australian Heritage Commission National Estate in 1995 and subsequently included in the Commonwealth Heritage List in 2015. And, busloads of school students and their teachers from around the country now frequently visit the embassy to learn from the Elders and other First Nation community leaders, who continue to tenaciously keep vigil for sovereignty and self-determination.

Author’s note: The Anglican Church Southern Queensland’s vision for Reconciliation is for “a future of openness where the First Nations peoples will be restored to a place of equity, dignity, and respect.” Under the core Reconciliation Action Plan pillar of “Respect”, we have committed “to raise awareness…of pathways to greater recognition and self-determination of First Nations peoples” and to “Increase understanding, value and recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, histories, knowledges, and rights through cultural learning.”

“At the end of my final tutoring session, the student’s parents thanked me with hand painted gifts, including a rock featuring the Aboriginal flag on one side and “The Aboriginal Tent Embassy 1998” on the other. It sits on my work laptop right next to the start button, so it’s the first thing I see when I commence work each morning” (RAP Working Group member, Michelle McDonald)

“Aboriginal Tent Embassy 1998” is painted on the other side of this rock (thanks to Linda Burridge at St Francis College for assisting with the photography)