Not quite present: art and faith

Reflections

“Art, like faith, risks itself within a world that is there not as a given to be reproduced, but as a blessing to be offered, shared and formed,” says Dr Peter Kline from St Francis College

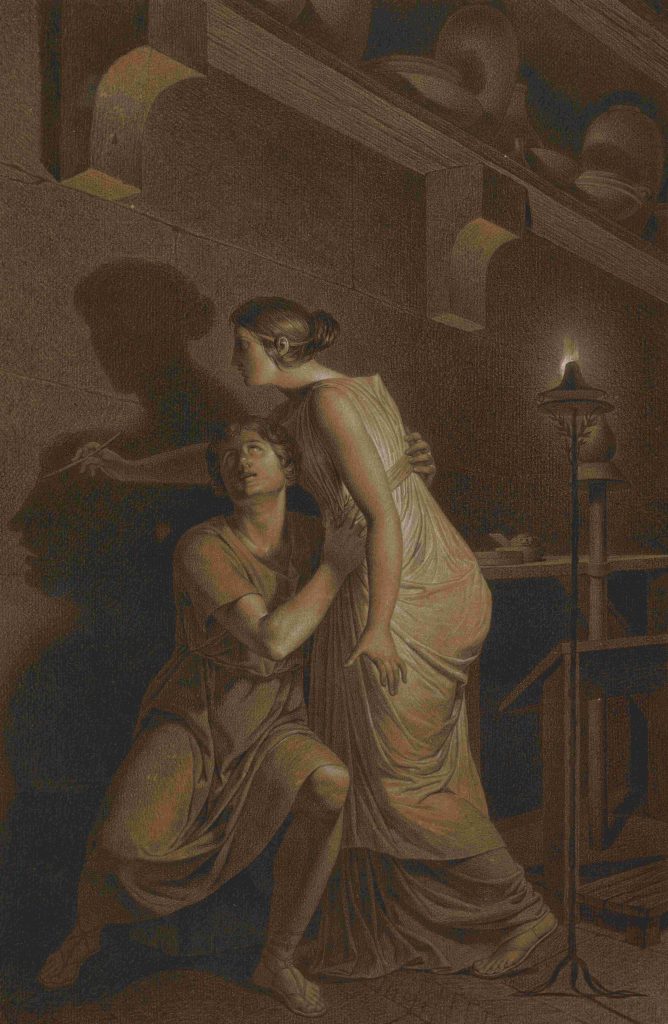

There are numerous myths about the origin of visual art that circulate within various cultures. One of the most suggestive comes from the first century Roman author Pliny the Elder, who tells a story of the invention of drawing by a Corinthian woman. On the eve of her lover going off to war, she traces his shadow on the wall of her house. The first image is born. In that moment, visual art comes into existence.

Joseph-Benoît Suvée (Belgian, 1743 – 1807) The Invention of Drawing (recto); Sketch of Lower Leg Bones of Human Skeleton (verso), about 1791; black and white chalk (recto); graphite (verso), on brown paper (Image courtesy of Getty Museum Collection)

How to interpret this story? What is it telling us about the truth of visual art? One way to interpret it would be along Platonic lines. In Greek philosopher Plato’s famous “allegory of the cave,” human beings are forced to watch a play of shadows on the wall of the cave in which they dwell. They mistake these shadows for reality itself and so remain unenlightened, slaves to their own ignorance. What they need is a teacher who can liberate them from their attachment to shadows by leading them out of the cave into the real world.

Advertisement

If we interpret Pliny’s story within this framework, painting comes into existence as the birth of “representation”. The Corinthian woman creates a “stand in” for the reality of her lover, who is going away. As such, her artwork is at best a derivation. Drawing, or the visual image in general, is a deficient or “less real” phenomenon than the thing itself, reality itself — just as a person’s shadow is merely a derivate appearance of a person’s form. Attachment to images would then be akin to an unenlightened attachment to shadows, to mere appearances, to what is not fully real. The male lover, the enlightened human being, leaves the cave and goes off to war, while the woman stays at home in the cave and gazes at the images, at the shadow.

What if we played with Pliny’s story differently and freed it from a Platonic interpretation? What if we let it become instead a myth about the tensions and depth of visuality and the role of art in giving us access to and keeping us in touch with the profundity of seeing and looking as the finite beings that we are? What if we let the cave with its shadows be the sight of truth itself rather than its occlusion?

Advertisement

A different interpretation of Pliny’s story might proceed by centering not the distinction between reality and its representation, but rather what drives the tension of the scene, namely, the woman’s desire. Gazing upon her lover on the threshold of his departure, the origin of drawing happens when she sees something she has not seen before, or she sees a truth in what she had previously only registered as a mundane occurrence. Noticing her lover’s shadow upon the wall, the woman suddenly feels a poignant truth, that her lover in a sense is already gone, that he has always already left, that his presence is at the same time a kind of absence, an arrival that is also a departure. She sees the fragility and fleetingness of his existence in his shadow, not as derivative of reality but as constitutive of it. Tracing her lover’s shadow is what lets her touch his finitude, the wondrous passing of his existence. She does not represent her lover; she presents her lover at the threshold of appearing and fading away. Drawing lets her see — and show — this sacred threshold that opens all presence:

“Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.”*

At the origin of art is not representation (presenting a “copy” of reality), but desire reaching out to trace and show the finitude of existence — and in doing so consenting to it. Rather than demand that her lover stay, or that she go with him, the Corinthian woman engages the space of her lover’s difference from himself, his passing, the open time and space of existing. She sees it, or sees that she sees it, and the line of her tracing draws out a non-acquisitive desire. Drawing comes into existence as an activity that hosts the finitude of things, the arrival of their departure. It lets beings be.

Another way to say this is that the origin of art is wonder — that astonishment that arises when what is familiar becomes strange or new. Art is rooted in the desire to show the wonder of things, that things are not simply closed in on themselves, while spaced from themselves and so always more than themselves. This not-quite-presence of things constitutes their desirability, and art materialises this desirability in what it shows.

Art, then, might itself be understood as an act of faith, if faith is understood as entrusting oneself to and engaging oneself with a world that goes beyond our ability to master it, a world that goes beyond itself. A world that did not go beyond itself toward what religions call “God”, or toward what might be called the sacred or the divine, a world that did not open beyond itself beneath a sky that illuminates it from beyond, a world collapsed on itself, perfectly at one with itself, given, completed, finalised, could not be drawn. Nor could it be sung or danced or filmed or narrated.

Art, like faith, risks itself within a world that is there not as a given to be reproduced, but as a blessing to be offered, shared and formed. It gathers, intensifies and opens the world’s visuality like singing gathers, intensifies and opens breath and language. Sight becomes no longer merely functional or useful — it tips over into pleasure, into joy.

* Paul Klee, “Creative Confession,” in Creative Confession and Other Writings (London: Tate, 2014), 1.

Author’s note: If you would like to engage the intersection of art and faith, please come to the 2023 David Binns Memorial Lecture at St Francis College on Thursday 2 November at 4pm. Dr Alexandra Banks, a recent St Francis College PhD graduate, will deliver a lecture titled, “Broken Bodies, Broken Words: Feminist Theology, Trauma, and the Arts.” The event is free; however, please register on Eventbrite for catering purposes.