Two childhood friends serendipitously reunited through anglican focus

Features

Two Queensland women who grew up together on the Daintree Mission reconnected for the first time in more than 30 years recently, following the publication of a ‘Spotlight Q&A’ in anglican focus. In this special joint reflection, Kuku Yalanji Elder Aunty Janice Walker and Anglicare Administration Officer Veneta Tschumy tell some of their story, along with Aunty Janice’s daughter, Anglicare Cultural Support Worker Lalania Tusa, who serendipitously brought the childhood friends together through her Q&A

Please note: First Nations peoples should be aware that this content may contain images or names of deceased persons.

Two Queensland women who grew up together on the Daintree Mission in Northern Queensland serendipitously reconnected for the first time in more than 30 years recently, following the publication of a ‘Spotlight Q&A’ in anglican focus.

In June this year, the author of this Spotlight Q&A, Kuku Yalanji woman and Anglicare Cultural Support Worker Lalania Tusa, received a surprise email from fellow Anglicare staff member Veneta Tschumy, after Veneta read the Q&A, informing Lalania that she grew up with Lalania’s mother in Mossman. Veneta’s parents ran the mission where Lalania’s mother, Aunty Janice Walker, spent the early years of her childhood.

Veneta and Aunty Janice, a Kuku Yalanji Elder and Traditional Owner, then reunited in St Martin’s House earlier this month to catch up on news, reminisce and exchange photos. Aunty Janice and Veneta also shared with the anglican focus Editor about their experiences growing up on the mission, the effects of discriminatory Government policies, the resilience of First Nations peoples, the importance of truth telling, and their hopes for Reconciliation. Lalania, whose mother, maternal grandfather, maternal aunty and maternal uncle were all taken from their families, also shared about the intergenerational trauma experienced by family members of Stolen Generation survivors.

Aunty Janice Walker and Veneta Tschumy (far left) at the Mossman Show in 1960

Aunty Janice – Kuku Yalanji Elder and Traditional Owner

When my mum and dad were married, they had to get permission from the police sergeant, who also had to be present at the wedding. Everything had to go through the Chief Protector and Police. Even though my dad was not always paid by the farmers he worked for, he saved enough for a car because he was very good at budgeting. But, the police would not permit him to purchase the car.

Advertisement

I was taken from my family at the age of two years old and put in the dormitory on the mission. Only three of the nine surviving kids in my family were stolen, as only the lighter skinned children were taken because the government expected light skinned Aboriginal children to assimilate. The hardest restriction living on the Daintree Mission to deal with was being taken from my mother and father and brothers and sisters. When I had permission to spend time with my parents and other siblings, which was only at church events, I didn’t want to leave them and go back to the dormitory. It was only when I moved back in with my parents after my schooling that I got to know them as I was taken away so young.

I was not allowed to speak my language on the mission or at school. At primary school we were wrongly taught that Aboriginal people were cannibals. Even the school books said this. It wasn’t until I was living in a state home in Garbutt and attending Pimlico State High School when I was a teenager that I found out that I was Aboriginal. I didn’t want to be Aboriginal as I was taught that Aboriginal people killed and ate people.

Advertisement

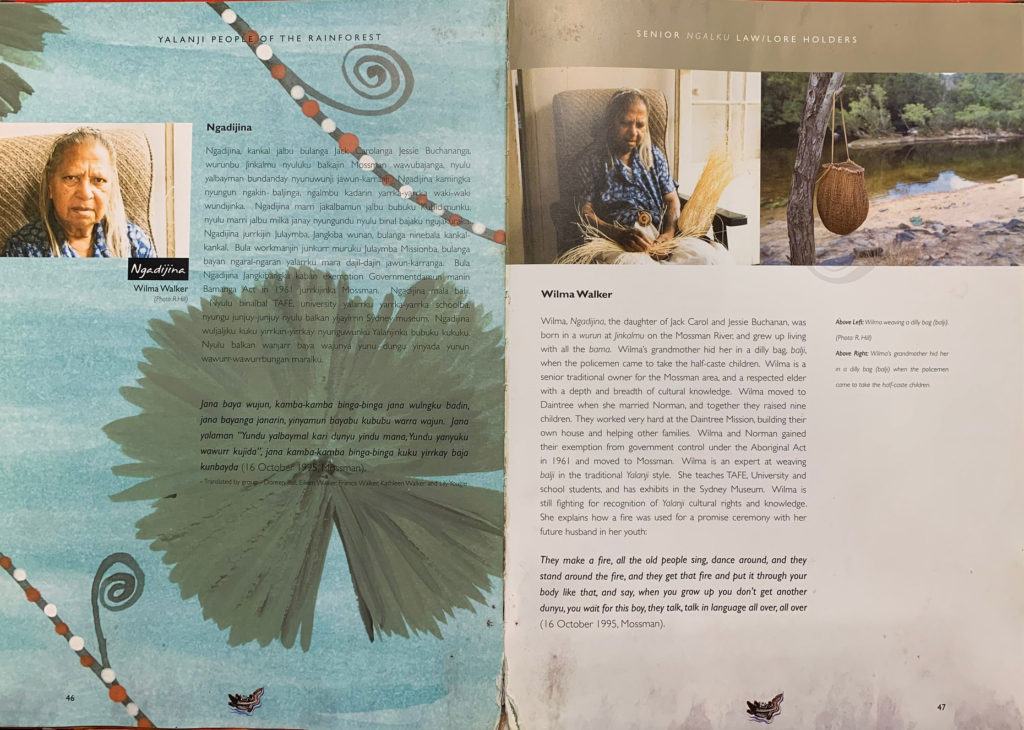

My father, Norman, was taken from his family’s camp at the age of seven when he was playing near the Daintree River and sent to Palm Island to a boys’ dormitory. My mother, Wilma (Ngadijina), was hidden by her family in a dilly bag (balji) whenever the police came to take lighter skinned children away. Then when my father was 19 and my mother was 13, they were rounded up with lots of other Aboriginal families and put on the Daintree Mission.

Aunty Janice Walker’s mother Wilma (Ngadijina) was hidden in a dilly bag (balji) whenever the police came to take lighter skinned children away, as told in the Yalanji Waranga Kaban: Yalanji People of the Rainforest Fire Management Book (2005)

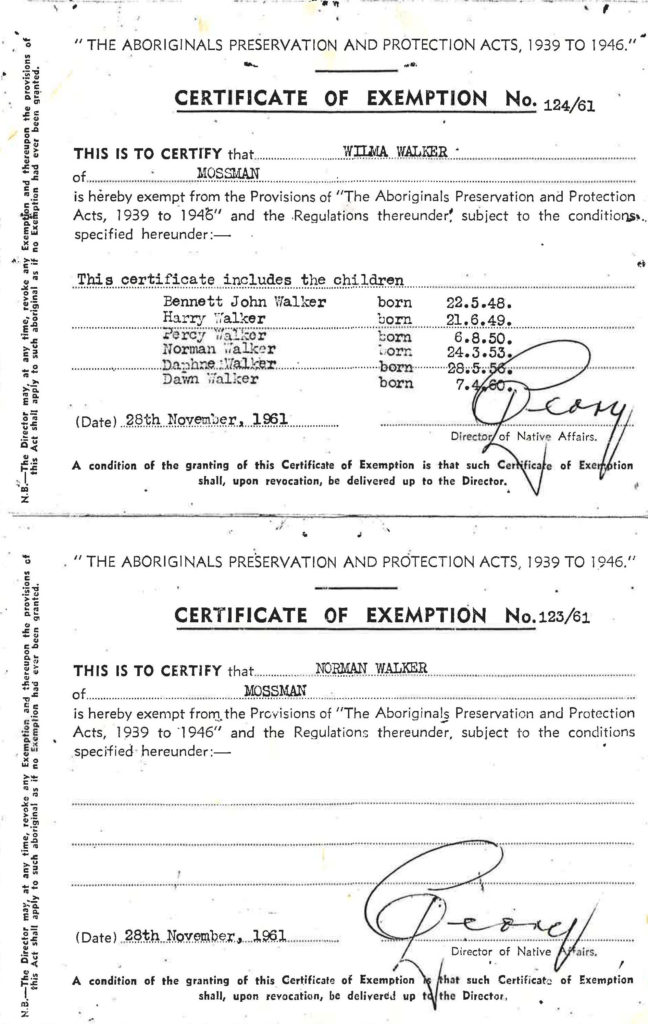

Both my parents were given an exemption certificate in in 1961, which meant that they were permitted to make decisions for themselves. All of their kids were listed on the certificate except those that were taken from them – me, Pam and Kevin. So, I always say, “I am still not free.” Aboriginal people had to produce their certificate to the police on demand in order to travel freely and make autonomous decisions, including where they lived and who they married. Exemption certificates were not abolished until the 1967 Referendum when Aboriginal people were finally granted full civil rights.

“Both my parents were given an exemption certificate in in 1961, which meant that they were permitted to make decisions for themselves. All of their kids were listed on the certificate except those that were taken from them – me, Pam and Kevin. So, I always say, ‘I am still not free’.” (Aunty Janice Walker)

Our people suffered from losing their families and their homes because they were removed from their family camps, then taken to the mission, and then pushed out to society to fend for themselves. Break up of family kinship resulted from the separation of family members; for example, sisters and brothers who were light skinned were separated from darker skinned siblings.

Our traditional language has been affected in a negative way due to children being punished if we spoke ‘language’. We were banned from speaking any language other than English on the mission and at school on the mission. The introduction of rations has caused health problems, such as diabetes, because our people lived on healthy bush foods and hunted prior to the rations.

Because of our resilience, the positive effects have been that we are an even more strong-minded, determined family who want our children to achieve and stand with our heads held high in society, which is an outlook that has been passed down by our parents who have lived through the mistreatment of Aboriginal peoples through the Government’s assimilation policies.

For Reconciliation to take place, Australia’s early history and the mistreatment of Aboriginal peoples through Government assimilation policies needs to be acknowledged by the current Prime Minister and current Federal and State Governments. The true history also needs to be taught in every school in Australia and every organisation should have mandatory cultural awareness training, including the police force, the education system, the health system, private businesses and all sectors of the workforce. If this happens, then maybe we will start to see Reconciliation and the curbing of the racism that is so prevalent in Australia.

Veneta Tschumy (front, sixth from right) and Aunty Janice Walker (front, seventh from right) on the Daintree Mission, circa. 1960-1961

Veneta Tschumy – Administration Officer, Anglicare Southern Queensland

When I read Lalania’s Q&A I emailed her to introduce myself as her mother’s childhood friend and wrote that, “I was excited to just read your story in anglican focus – if your mum is ever down here, I would love to catch up with her. We were mates as children on the Daintree Mission.”

It was great to catch up with Aunty Janice earlier this month – the time with her went far too quickly, as there was so much to talk about. How special – the years rolled back, and I’ve spent the days since reflecting on our childhood and reminiscing with my mum and sister, who is old enough to remember those days. Our plan now is to definitely stay in touch.

My parents were pastors and they ran the mission where Aunty Janice and I grew up. We played rounders and dress-ups together, attended church together and went to school together. We went to a two-teacher school and ‘us mission kids’ made up the majority of the school – the only difference was that ‘white’ children like me went to our home at the end of the day, while the Aboriginal children had to go to the dormitory. Aboriginal children were not allowed to leave the dormitory grounds without permission. I could go to Janice to play with her, but she could not come to me.

Aunty Janice Walker (centre) and Veneta Tschumy (left) on the Daintree Mission in December 1965

I have often spoken over the years how indignant I felt when I heard about the ‘free ticket’ (the exemption certificate) that the Walker family had to ‘achieve’ to be free and the unfairness of the system at that time. If a nine-year-old child can feel indignation, I felt it. Even at nine or ten years old, I knew that it was wrong that Aboriginal people were restricted in their movement. Although it wasn’t until many years later that I realised that at that time Aboriginal people weren’t even included in the Census. I then felt more indignation.

My position was always that we all bleed red blood – the colour of our skin might be different, but we are all created the same. I think that education plays a big part in changing attitudes. My granddaughter has been involved in a First Nations programme at school, which has been wonderful, but it would be great if this programme was available to all children who aren’t Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Fortunately, changes have slowly been happening since the years when I was a child, but obviously there is still room for improvement.

“Mum has always grounded her children in our identity and taught us to know who we are and where we are from” (Lalania Tusa, pictured with her mother Aunty Janice Walker and Veneta Tschumy at St Martin’s House, Ann St in August 2020)

Lalania Tusa – Kuku Yalanji Traditional Owner and Cultural Support Worker, Anglicare Southern Queensland

The flow-on effects of intergenerational trauma that stem from Government assimilation policies are still felt by many people across the nation. The survivors of the Stolen Generations have strived to pass on the little language and traditional practices left to each generation, but we have lost most of it due to Government assimilation policies. Families are still trying to find their relatives today, to the point where some people do not know whom they are permitted to be in romantic relationships with because children were scattered across the nation when they were taken from their homes and often don’t know who their family members are.

The sacred places that hold significant ceremonial meanings and practices have also been disrupted because of tourism, mining and other reasons. As a result, the passing down of traditional knowledge and practices has been dismantled.

Every person has an important part to play in achieving true Reconciliation in this country. I have often found Australia to be a racist country that does not have First Nation people’s best interests at heart. If we looked at each other through the eyes of God, with no prejudices and only with love, then we can start to heal and work together in harmony.

My mother is a true leader in our community and has always worked hard in maintaining our cultural ties and practices within our family and extended family. At night, she feeds Aboriginal people who sleep under the Foxton Bridge, many of whom were stolen, and cooks nutritious stew every week to feed families who are struggling. She loves the Lord – everything is the Lord for her.

My mother has educated primary and secondary school children for years about the Stolen Generations and she supports the teaching of Kuku Yalanji language in schools. She also gives the welcome to country for the mayor when important visitors come to Mossman and she runs the Indigenous Ministry Links church at the gorge, which Veneta’s dad coincidentally built. She fought to keep this church from being destroyed about 20 years ago and organised for its repair. Because of all of this work and her character, she is very well regarded in the Mossman community.

Mum has always grounded her children in our identity and taught us to know who we are and where we are from. Our family history has been at the forefront of our upbringing and has helped shape me to be the person that I am today.