“I try to put God at the centre of my life”: says Australian emergency medicine physician who recently volunteered in Gaza

Reflections

“I sought God’s blessing and dealt with the ‘What if?’ scenarios through prayer. I knew that I needed to accept that death was very possible in Gaza. I wrote my will, cleaned my rented unit and gave a friend my car keys before I left — just in case. Because I wasn’t scared of death, I think I was more effective and focussed on my work in Gaza,” says British-Australian emergency medicine physician Mohammed Mustafa

Please be aware that this reflection contains graphic and very distressing content.

I will always remember my first day volunteering in the Gaza hospital emergency department.

I walked into the ED and suddenly found myself in charge because I was the most senior doctor. The hospital was being run by medical students after doctors had either been killed, abducted or injured.

It was chaotic — hundreds of people had filled the emergency department following a mass casualty event caused by a drone strike.

The bodies of 10 children wrapped in blankets were brought in by their parents and other family members.

I recall the first blanket I opened — the body inside the blanket was of a child with their head missing.

I just froze in shock for about 15 seconds.

One of the most common questions people ask me is how I prepared myself for the one-month medical aid mission to Gaza in June this year.

I explain that I sought God’s blessing in prayer and that I sought my parents’ blessing in conversation.

In Islam, parents have a strong influence on you into adulthood. When I told my parents, my mum was really upset at first. After she thought about it, she called me back and said that: “Life and death is not in the hands of Israelis — it’s in the hands of God. I am not going to hold you back from helping people in Gaza.”

I sought God’s blessing and dealt with the “What if?” scenarios through prayer. I knew that I needed to accept that death was very possible in Gaza. I wrote my will, cleaned my rented unit and gave a friend my car keys before I left — just in case. Because I wasn’t scared of death, I think I was more effective and focussed on my work in Gaza. In emergency medicine, particularly in mass casualty events, you need to be able to take charge, even when drones are striking and bombs are going off in the background. So, I made peace with it.

I try to put God at the centre of my life. In Islam, we are taught from a young age that: “Whosoever of you sees an evil, let him change it with his hand; and if he is not able to do so, then [let him change it] with his tongue; and if he is not able to do so, then with his heart (Hadith 34).”

So, being compelled to volunteer in Gaza as an emergency department physician was about making a change with my hands. I decided that with my hands, coupled with my skills, I could help alleviate the oppression I was seeing on my screens at home in Australia.

Since returning from Gaza, I have been making the change with my mouth — by speaking on radio and television about what I witnessed and at fundraisers and other community events.

I have also been making the change through my heart via prayer. My faith was strengthened on the medical mission, especially by witnessing the faith of Palestinians who say Alhamdulillah, which means “Praise be to God”, in the most tragic situations. Even in the most heartbreaking moments when a child dies, they thank God for the gift of their child’s life and for the time they had with their child, trusting in God’s higher purpose. The Palestinian people I met in Gaza have a level of faith and trust in God that I can only dream of.

Palestinians see themselves as Palestinian first. I saw Christian and Muslim Palestinians working together in the hospital grounds, eating from the same plates and sleeping in the same rooms. I would only know the difference if I saw a Palestinian wearing a cross or if I saw a Palestinian praying. They see themselves as Palestinian first — as inhabitants of the land.

The faith of the Palestinian people shone though in their resilience and dedication to each other.

Every day I saw young nursing students — 19- and 20-year-old women — comforting injured and dying children in their arms. For many of these students this is their one job, day in and day out. When one crying or screaming child dies, they then pick up another. The only thing they can do in a mass casualty event is to pick up a child or baby and sit on the hospital floor, cradling and comforting them. Some of the children and babies they hold are severely disfigured from injuries, starving or burnt. I think a lot about these brave young nursing students and how difficult and traumatising that must be, especially when they are hungry and tired and grieving the deaths of their own family members.

Most of the patients I cared for in Gaza were babies and children. In the 24 hours prior to writing this, the United Nations described Gaza as “a graveyard” for children — 17,400 children have been killed in Gaza since October last year. Thousands more are dead under rubble. Hundreds of thousands more are injured and starving. More children have died in Gaza than in all of the world’s wars, conflicts and invasions in the last four and a half years combined.

“Most of the patients I cared for in Gaza were babies and children. In the 24 hours prior to writing this, the United Nations described Gaza as “a graveyard” for children — 17,400 children have been killed in Gaza since October last year,” (Australian emergency medicine physician Mohammed Mustafa in Gaza in June 2024)

Throughout each day I had to decide which child I attended to and which child I had to let bleed out on the hospital floor. I find myself looking back and wondering whether I should have helped one child instead of another.

I had to perform procedures on children without anaesthetic or pain killers, including putting in chest drains — tubes — to re-inflate lungs that collapsed after being crushed by rubble or wounded by gunshot. The excruciating pain is the same as being stabbed deep into the chest.

I had to peel the burnt and broken skin off a newborn baby. I had to perform procedures on children to reduce fractures caused by buildings that collapsed on them during carpet bombing. I pulled out shrapnel from children’s bodies. I prepped children, who had limbs blown off, for theatre by stopping the bleeding and strapping the remaining limb with a tourniquet.

Chillingly, I saw a lot of children who were killed or wounded by a single gunshot to the head. Children are being deliberately targeted by Israeli snipers in the genocide.

I also witnessed incredible courage among young children. A nine-year-old boy has learnt to insert cannulas, so he bravely goes out with the paramedics, even while bombs are going off, to put cannulas in. He brought patients to me in the emergency department. It was chaotic in the emergency department, and he can’t go to school, so this is what he does to care for his people.

Another child shared with me about how he had to run for his life after seeing his heavily pregnant mother run over by an Israeli tank.

There is no sanitation or cleaning products — no antiseptic, no gauze for wound cleaning and no medical-grade skin cleanser. I saw maggots growing in the wounds of Palestinian children.

There was one thermometer and one blood pressure monitor in the hospital’s whole emergency department.

There were no dressings for burns — children with severe burns to 60 per cent of their body cannot have their wounds dressed properly.

There is no way of checking blood sugar levels because there is no glucometer and no blood glucose test strips. Diabetic patients are going into life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis, and their symptoms cannot be managed properly.

I took eight bags of previously approved medical supplies with me from Australia — however, the day before we departed, this approval was revoked and so I could not bring them in. We were very limited in what we could take into Gaza. Other than clothing, shoes and the like, we could only take three kilograms of food for personal consumption.

There also aren’t enough doctors — more than 300 healthcare workers have been unlawfully detained and more than 595 have been killed, with the names of an additional 420 healthcare workers pending.

One of the Palestinian healthcare workers I worked with has shrapnel stuck in his hip. His family has been killed. During a procedure I asked him to assist by picking something up, but he was unable to bend over because of the shrapnel. Despite his injury and mourning the killing of his family, he does 24-hour shifts. Palestinian healthcare workers like him work for 24 hours and then go home for a rest amidst bombing to a tent. It’s hard to coordinate rosters when staff are dying as they are travelling to and from the hospital. I never knew at the end of my shift if I was going to see them again.

Despite the desperate need for doctors and nurses, it was a long and difficult process for me to get into Gaza. Israel limits the number of medical aid workers who can enter Gaza. Israel also bans doctors with Palestinian parents or grandparents from applying. This is very disheartening for Australian Palestinian doctors and other healthcare workers who want to help their people.

Initially we had 23 doctors and nurses who were given the go ahead to join our medical team in Gaza. However, in the end only seven of us were permitted in. Some were turned away at the border by the Israeli authorities and some were refused one day or one week before their scheduled arrival date after being initially approved.

A group of Jordanian doctors left Jordan the day after my team. They were arrested by Israeli authorities because they tried to take in baby formula, which was banned. Hamas aren’t babies. We saw young children and babies starving to death unnecessarily. Starvation is being weaponised in this genocide.

I saw emaciated children daily. Children are starving to death because Israel is not letting enough food through. Babies are starving because their starving mothers can’t produce milk. I saw many children and babies die in the emergency department due to starvation.

As well as drone strikes and bombings, Israeli soldiers are also doing controlled demolitions, including of paediatric hospitals. This is another way babies and children are being targeted.

After I returned home to Australia, it took many weeks before I could hold a child again. The first time I met my nephew, I couldn’t pick him up because of the number of dead Palestinian children I held and the number of children’s limbs I had picked up in the hospital.

If there is one thing I want readers to take away it is that this is a humanitarian crisis that transcends religion.

I felt guilty leaving Gaza. I miss the Palestinian people. I hope to return soon.

ACSQ Justice Unit note: Here are three things you can do to help the Palestinian people in Gaza:

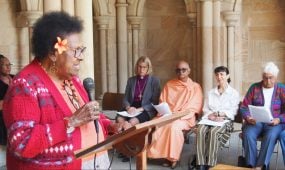

- Join in a “Gathering to Pray for Gaza and all Palestinians” inter-faith peace prayer vigil, with the theme “Palestine: A Land with a People”, between 6.45pm and 7.45pm on Saturday 30 November 2024 in Brisbane Square (at the top of Queen St). See ACSQ Facebook and the anglican focus Events page for more information. Thank you to the more than 80 recognised inter-faith and multi-cultural leaders who have helped lead “Praying for Gaza” ceasefire prayer vigils in Brisbane since March.

- Contact the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Senator the Hon Penny Wong, calling for her to pressure Israel into letting food and medical aid and aid workers into Gaza, in line with the International Court of Justice’s legally binding orders. And, contact Senator the Hon Penny Wong calling for her to pressure Israel into allowing healthcare workers from Australia (and other countries) of Palestinian descent into Gaza.

- The Anglican-run Arab Ahli hospital in Gaza was hit in October by Israeli strikes — if you are able, please donate to the Anglican Board of Mission AID Gaza hospital emergency appeal.