Aboriginal art practices, stories and symbols

Features

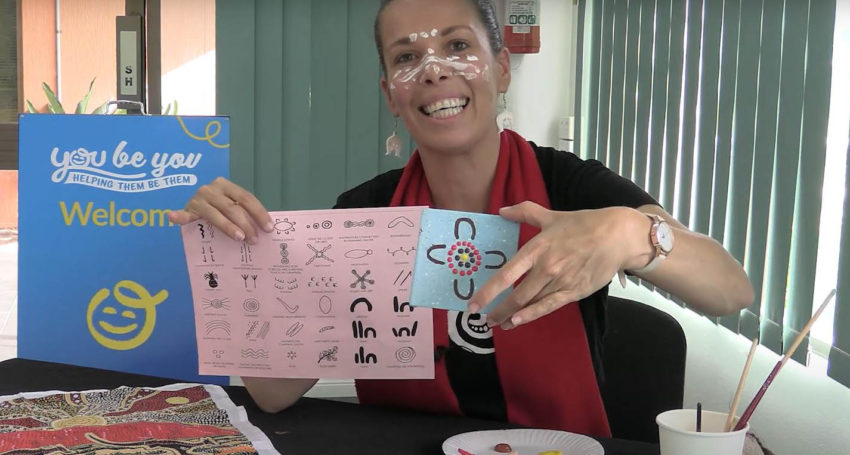

“Symbols in Aboriginal art are used as a means of communication for people, and for documenting histories, Country boundaries, ceremonies and food sources,” says Anglicare Cultural Support Worker and Kuku Yalanji artist Lalania Tusa, while inviting readers to join her in a dot painting workshop at a festival at St Francis College in October

Australian First Nations art is the oldest ongoing art tradition in the world, with the earliest artworks, including rock carvings, body painting and ground designs, dating back more than 40,000 years.

There are several types of Aboriginal art and ways of making art. These include rock and cave art, stone art, rock engraving, dot painting, bark painting and etching, wood carving, sculpture, dilly bags, baskets, fish trap weaving, sand art, ceremonial art and body painting.

Advertisement

Rock art, for example, was traditionally painted with ochre rocks made of natural clay pigments and minerals found in the soil, as well as with charcoal from the fire. The ochre paints come in all different colours and are obtained from the local land that produces specific colours, such as white, pink, yellow, purple, blue, red and black. Most ochre is found in caves and along the riverbanks of coastal Australia. Today we largely paint with acrylic paints, watercolour and oil paints.

There are no traditional alphabet equivalents in Aboriginal languages, so it is extremely important for us to continue the tradition of creating art that captures and depicts the stories and information passed down through the generations. In doing so, we can recount songlines (Dreaming tracks), sacred landmarks, borders and boundary markings of given Nations, ceremonies, dances and songs, histories, and hunting and gathering practices. Aboriginal art is closely linked to religious ceremonies and rituals based on totems and Dreamings. Symbols in Aboriginal art are used as a means of communication for people, and for documenting histories, ceremonies, Country boundaries and food sources.

Advertisement

In 1971, the Aboriginal art world changed dramatically. A young schoolteacher, Geoffrey Bardon, arrived at the Papunya settlement – 250 kilometres west of Alice Springs. The government town was home to many different groups of desert Aboriginal peoples, including Pintupi, Luritja, Walpiri, Arrernte and Anmatyerre, who had been forced to move there in the 1960s under government assimilation policies. While in Papunya, Bardon noticed that Aboriginal men, while telling stories to others, were drawing symbols in the sand. He encouraged them to put these stories down on board and canvas, thus nurturing what was to become the worldwide Western Desert Aboriginal art movement. He also encouraged the local children to draw and paint the stories from their cultures.

The Aboriginal people of Papunya developed their own painting styles and representations of their lands, cultures and ceremonies. Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd has been incorporated by the artists, with the Aboriginal art movement now well-known worldwide.

The recognisable dot art medium has become known throughout Australia and the world through this development. Dot art is used by many Aboriginal Nations to tell stories in different ways and is deeply symbolic. In my work as a Cultural Support Worker, I pass on to First Nations children many symbols so they can continue the tradition of creating their own dot art. While showing the children how to create dot paintings, I give the students a take-home PDF handout showing some of these symbols, which include representations of people, animals, tools, foods, and topography and weather features.

Related Story

Video

Video

Jarjums Connect: Aboriginal art practices

Aboriginal art has fostered cultural revival in an extremely good way for our people following the intentional harm done to our cultures during the implementation of former government assimilation policies. As the older artists teach the young, it has revitalised young people’s appreciation and knowledge of their cultures. There have also been several other benefits, such as increasing First Nation self-esteem and cultural pride, building stronger bridges of understanding with non-Indigenous people and, most importantly, preserving the central function of Aboriginal art with the passing on of vital information for generations to come.

You are invited to join me at On Earth Festival on Saturday 16 October at St Francis College in Milton to learn more about First Nations art techniques, stories and cultures. You will be guided to create your very own inspirational piece and have the opportunity to ask me any questions you have about the traditional ways of Aboriginal First Nations art practices.

Editor’s note: Book online now to join Kuku Yalanji artist Lalania Tusa at the On Earth Festival on Saturday 16 October at St Francis College in Milton.