Complexity in understanding Country and culture

Reflections

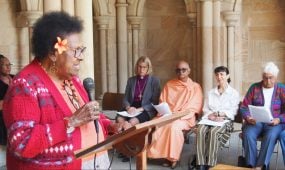

“Our languages are the most complex in the world, such that even groups within the same language group have difficulty speaking to one another. Language is contextual – we have words for those things that pertain to our space. In the Wiradjuri language, for example, there is no word for ‘sharks’ as they do not exist in our universe,” says Wiradjuri artist and priest The Rev’d Canon Glenn Loughrey

To write about climate change and complexity from an Aboriginal/Indigenous point of view is not simple or complicated, but is itself complex. Why? Complexity sits at the centre of Aboriginal life and is the integral driver of engagement on and with Country and all kin who live therein.

Perhaps a good place to start to unpack this complexity is with the ubiquitous Acknowledgement of Country we are all familiar with:

“[St Oswald’s] acknowledges the continuing custodians, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation on whose land we live, work, play and pray and acknowledges their elders past, present and emerging. We also acknowledge that this land was stolen and is still be returned to them.”

In the acknowledgement that we give in person, we recognise the context in which we are, that there is a particular people who remain the custodians of the Country and that all elders in the story of that nation continue to contribute to the life of the Country. We recognise clearly, despite all our efforts to live here, that it is not our space. It has not been given to us as ours and we are to live in a relationship with those who are integrally part of it in a way we cannot be.

This statement recognises there are many independent autonomous Nations on this land we now call Australia and that each lives in its own particular context, culture and language. Some 270 plus language groups and over 700 dialects spread across “Australia” means we are to avoid speaking of First Nations People as if they are one group. We are not.

It then becomes further complex when we remember the invasion and genocide impacted unevenly across “Australia”. The south-eastern sections of Australia were the first to be impacted and suffered the most brutal treatment, such that many Nations were decimated to the point of extinction. Those that were not, lost access to the homelands and became part of the diaspora spread across the south-east. This means that local knowledge has disappeared in many areas in terms of customs, language and how people lived in relation to their universe, their particular Country.

Advertisement

Aboriginality is high-context identity. It is the reason we describe ourselves first by our Country of origin even before saying our name. Our languages are the most complex in the world, such that even groups within the same language group have difficulty speaking to one another. Language is contextual – we have words for those things that pertain to our space. In the Wiradjuri language, for example, there is no word for “sharks” as they do not exist in our universe.

Aboriginality is high-context identity because our universe, our Country, is intimately different from the universe or Country near to ours. Why? Types of soil, vegetation, flora and fauna and water flow change continuously across each space. A mistake we make is to generalise what an acre of land may be like. It may look the same, but in fact have a variety of ecosystems within that one small space. This requires contextuality in relationships to know and live with. I use the terms “to know” and “live with” to avoid the technological mindset of analysing and managing. You can only know your space if you walk and develop the necessary relationship to understand it, and for it to understand you. It is not an object but a subject, just as you are.

Advertisement

That is why we use the term “custodial” to describe this relationship. A custodial relationship is one built on responsibility and reciprocity. It is not about extraction or use for one species, in this case, humans. It is about how we live with our kin, other people and all of nature’s created beings, animate and inanimate, in a way that all can flourish now and into the future. In a custodial relationship, all recognise that they are citizens of a limited space and are to ensure they care for each other, so all have what they need at all times.

In such a high-context situation care for Country is nuanced, sophisticated and related. While the principles underpinning a custodial relationship with kin are similar in each Country, the way that is worked is local and particular. The principles, for example, of cultural burning follow closely with listening to and engaging with what the local landscape, climate and needs are; the process of burning, its timing and its extent depend on what is appropriate in that place. The relationship with water, like fire, is local and particular and is not approached as a utilitarian many, but as one element of the web of meaning, purpose and sustenance for not just the people, but all they interact with.

Both these, amongst all other contacts with Country are about life, the giving and maintaining of life and not about use or even survival. It is not about the preservation or salvation of creation, but about empowering life in all its forms.

It is complex, but simple – there is enough for all if those who can do not take more than what is theirs to have.

An earlier version of this was first published in the December 2022 edition of The Eagle, the magazine of St John’s Cathedral. Read the latest edition of The Eagle online.