“Let’s acknowledge the good news that domestic and family violence is preventable”

Features

“My involvement in the domestic and family violence space began when my sister, Allison Baden-Clay, was murdered by her husband in April 2012. Her story shocked and gripped the nation. It resonated with people in the community and was in the media almost daily for months. At the time my family wondered why there was so much interest in Allison’s story,” says Vanessa Fowler OAM from St Paul’s, Ipswich and the ACSQ Domestic and Family Violence Working Group

Story Timeline

Listening to and supporting survivors of domestic and family violence

The month of May brings with it the joy of Mother’s Day when we come together to celebrate the achievements of mothers, grandmothers, carers and women everywhere.

Yet May is also significant in the domestic and family violence space because it is recognised as Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Month. This dedicated month is not only a time when we highlight the lives lost each year, but it is also an opportunity to promote awareness, to educate the community and to reflect on how far we have come over the last decade while looking to the future and the work that still needs to be done. This is also a time when women are calling for change, pleading to be listened to, and asking to be believed. I am a part of this movement for change and have been for many years.

My involvement in the domestic and family violence space began when my sister, Allison Baden-Clay, was murdered by her husband in April 2012. Her story shocked and gripped the nation. It resonated with people in the community and was in the media almost daily for months. At the time my family wondered why there was so much interest in Allison’s story. We came to the conclusion that it was because she was “the girl next door”, a neighbour, a kind friend. Allison was well educated, a high achiever, a successful business woman and a loving and devoted mother. Allison, like so many other women, suffered in silence until her death.

Growing up, Allison was always a quiet achiever, and achieve she did. She was deputy Head Girl at Ipswich Girls’ Grammar School, Miss Brisbane in 1994 and graduated with honours in her Arts degree from the University of Queensland. However, her greatest achievement was her three daughters, whom she loved and offered every opportunity to succeed. Her positive attitude and desire to always strive to be the best that she could have been instilled in her children, whose lives were turned upside-down on 19 April 2012.

There is one very important thing that my family has learned over the last 10 years and that is that domestic and family violence can happen to anyone – to people of all ages, all classes, all religions and all income and education levels. Allison, like so many other women, suffered in silence until her death.

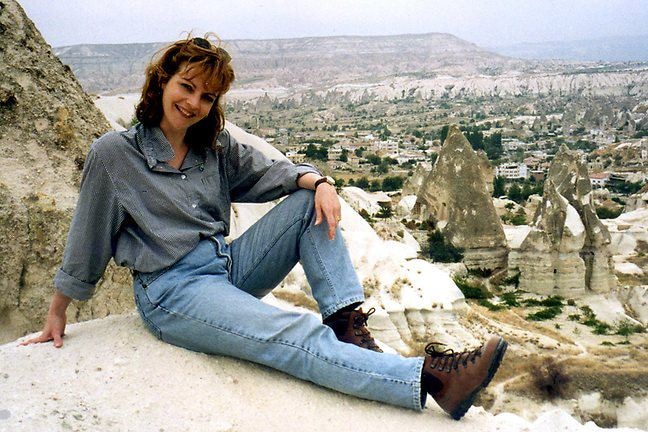

Allison Baden-Clay in 1997

Domestic and family violence isn’t just an “immediate family” problem. It’s a crime with serious repercussions for extended family members (especially children), friends and the entire community. Family members and friends are impacted and live with the consequences for the rest of their lives. It has a “ripple effect” – other family members are victims, too. I know because I live it.

As a society, we are commonly told to “mind our own business” when it comes to other’s family matters and to avoid intruding in other people’s affairs. So in a domestic and family violence situation this can sometimes make it hard for us to determine what to do, especially if we are worried about the possibility of “interfering” with a personal relationship, such as someone’s marriage. People are often reluctant to speak up if they suspect violence in the relationship of a friend, colleague or neighbour with the (mis)perception that “it’s none of my business”. Well, it is our business and we can break the cycle.

Advertisement

As a family, we now look back and realise that there were signs of abuse in Allison’s marriage – there was a pattern of abusive behaviour that we now know as “coercive control”. For example, the landline in their house was disconnected so that the only way the extended family could contact her was through her mobile phone, which her husband monitored. In addition, as a stay-at-home mum she had no personal funds to draw on and therefore relied on his income and his allocation of a weekly allowance. Bank accounts and credit card statements were checked and questioned by him. His emotional abuse led to her believing that she was overweight and ugly and she was subsequently discouraged from seeing family and friends, which isolated her. A final act of physical violence took her life. In hindsight, if we had known what to look out for then, Alison may still be alive and safe and the lives of Allison’s three children and her extended family members may have been very different.

Allison’s murder has changed many lives forever and it’s important to our family that Allison’s legacy is a positive one, and that by sharing her story we may help others.

It’s important to understand that gender inequality is a key driver of violence against women. Gender inequality provides the underlying conditions for violence against women. It exists in many areas of our communities – from how we view and value men and women; to economic factors like the pay gap between men and women; to intimate partner and family roles and expectations; and, to how we choose to either include or exclude women from hierarchies, including in church leadership.

Violence against women has distinct gendered drivers. Evidence points to four factors that most consistently predict or “drive” violence against women, explaining its gendered patterns.

- Condoning of violence against women occurs both through social attitudes and norms and through legal, institutional and organisational structures and practices that justify, excuse or trivialise this violence or shift blame from the perpetrator to the victim.

- Violence is more common in relationships where men control decision making and limit women’s autonomy, have a sense of ownership of or entitlement to women, and hold rigid ideas on what is considered to be “acceptable” female behaviour. Constraints on women’s independence and decision making are also evident in the public sphere where men have greater control over power and resources. Such forms of male dominance, power and control and limits to women’s autonomy collectively contribute to men’s violence against women by sending a message that women have lower social value and are less worthy of respect.

- Implementing, promoting and enforcing rigid hierarchical gender stereotypes reproduces the social conditions of gender inequality that underpin violence against women. In particular, reinforcing unhealthy stereotypes of masculinity plays a direct role in driving men’s violence against women. Men who form a rigid attachment to socially dominant norms and practices of masculinity are more likely to demonstrate sexist attitudes and behaviours, and consequently perpetrate violence against women.

- Male peer relationships (both personal and professional) that are characterised by attitudes, behaviours or norms regarding masculinity that centre on aggression, dominance, control or hypersexuality are associated with violence against women. In such peer groups, adherence to these dominant forms of masculinity increases men’s reluctance to take a stand against violence supportive attitudes, and can increase the use of violence itself.

This highlights the unequal structures and practices that prevent women and girls from enjoying the same opportunities and privileges as men and boys. So we all must actively challenge inequality in the places where we live, learn, work and play. We also need to avoid using inappropriately gendered phrases such as “it’s just boys being boys” or “it’s okay – he just punched you in the arm because he likes you” to excuse unhealthy behaviours, or “don’t run like a girl” or “don’t cry like a girl”. From a young age, boys and girls start believing there are reasons and situations that make sexist remarks and behaviours acceptable. This is dangerous and has serious and long-lasting consequences.

Advertisement

We need generational change. We need cultural change. We need to change the way we think about gender. We need to change our mindsets. However, change can only be effectively achieved when each and every one of us takes a personal interest and engages in promoting healthy and non-violent relationships in our homes, schools, work places and the broader community.

We shouldn’t have to raise our daughters to protect themselves against mistreatment from men, we should be raising our sons to respect and value them. As the mother of two sons, I am raising my sons to be strong, decent, generous and egalitarian human beings who treat others with kindness, integrity and leadership.

So during this month of May, let’s acknowledge the good news that domestic and family violence is preventable as we all work together towards a positive, safe and equal future for everyone.

Note from The Rev’d Gillian Moses, Chair the ACSQ Domestic and Family Violence Working Group: The Anglican Church Southern Queensland (ACSQ) is committed to promoting and supporting a safe environment for all. Domestic and family violence is unacceptable. We offer pastoral care to victims of domestic and family abuse. The ACSQ is part of the Queensland Churches Together Joint Churches Domestic Violence Prevention Project (JCDVPP), which publishes resources for clergy and lay people.

If you are in immediate danger, call 000 for police or ambulance help. For a list of helplines and websites available to women, children and men, visit this page on the Queensland Government website.