“The lives of Mary Magdalene manifested truth”

People & History

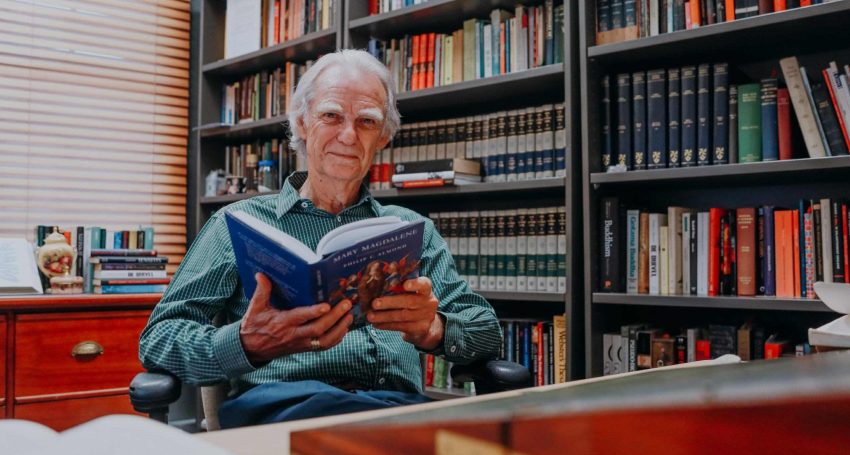

“At the centre of the story of Mary Magdalene there lies a paradox,” says Emeritus Professor Philip Almond

“She came to the sepulchre, laden with perfumes and aromatic herbs to embalm a dead man; but, finding him alive, she received a very different office from that which she had thought to discharge – messenger of the living Saviour, sent to bear the true balm of life to the apostles.”

Pseudo-Rabanus Maurus, The Life of Saint Mary Magdalene and her sister Martha (15th century)

Within Eastern and Western Christianity, Mary Magdalene is one of the most important saints. After Mary, the mother of Jesus, she is by far the most important female saint. This was because she was the archetype of the penitent sinner. It was she who most demonstrated to everyone that no one was beyond redemption. She represented the sinner we should aspire not to be and the saint we should desire to become.

Advertisement

At the centre of the story of Mary Magdalene there lies a paradox. We know virtually nothing of her. The New Testament gospels tell us little. According to them, she had once been possessed by demons, but they had gone from her. She may have come from Magdala. She was probably a wealthy woman who provided for Jesus and his disciples. She was present at the crucifixion and, we are told, she was the first witness to the resurrection. It was she, we read, who informed the disciples of Jesus that he had risen from the dead.

Yet, this very paucity of information made possible and necessary the construction within Christianity of an array of “lives” of Mary Magdalene over the next two thousand years. She would become a woman for all seasons — available for all times, adaptable to all occasions, and accessible to all people, both men and women. This was because there were many different Mary Magdalenes.

She was the penitent prostitute and the woman possessed with seven demons. She was the first witness to the resurrection and the first to inform the disciples of it. She was the wife and lover of Jesus and the bride at the wedding at Cana in Galilee. She was the model for the contemplative monastic life and the solitary desert dweller whose nakedness was covered by her hair. She was a symbol of the ascetic and the erotic. She was the female leader of the Early Church, the wealthy heiress, and the party girl from Magdala. Symbolically, she was the second Eve and the “bride” of Christ.

Advertisement

That there are many different Mary Magdalenes was also the result of her being identified with other female characters within the New Testament. In the Eastern Church, she remained the single Mary whose appearances in the New Testament we outlined above. But within the Western Church, from the beginning of the seventh century, she became a composite figure. For it was in the year 591 that Pope Gregory the Great identified her with two other women within the New Testament. On the one hand, she was identified as Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus. As Mary of Bethany, she had anointed Jesus’ feet with a costly perfume of pure nard and wiped them with her hair in the gospel of John. On the other hand, Mary Magdalene was also identified as the sinful woman of the gospel of Luke. She, too, had anointed Jesus’ feet with ointment from an alabaster jar, had bathed them with her tears, and dried them with her hair.

Mary Magdalene has emerged as the most important modern saint of the last 70 years within the secular West. She became Jesus’ wife and lover within a new array of contemporary lives of Mary that began with Nikos Kazantzakis’ book titled The Last Temptation of Christ, and she found recent fame as the heroine of Jesus Christ Superstar, the wife of Jesus in The Da Vinci Code and, most recently, in the discovery of an apparently ancient papyrus in which Jesus called Mary, “My wife”.

Related Story

Features

Features

Meeting the Gospel women

The many imaginings of Mary Magdalene have played a decisive role in the shaping of Western and Eastern religious belief and piety. Her history is a history of how many of her devotees perceived the relationship between the sacred and the profane, how they negotiated the connection between the spiritual and the material realms, how they experienced the transcendent in the everyday, how they thought about the natures of men and women, and how they were inspired by her life to implement her “personae” in their own.

Thus, the importance of Mary Magdalene ultimately lies in what she tells us about the religious life of humankind over the past two millennia. Her “lives” mattered because they were believed by many of her devotees to capture the truth of the person depicted. And the “true” events in the life of Mary Magdalene were endowed with transcendental meaning. Thereby, they created deep meaning in the lives of those living religiously through them. The lives of Mary Magdalene manifested truth. Through her lives, as Paul Ricoeur would put it in Figuring the Sacred (1995: 43): “new possibilities of being-in-the-world are opened up within everyday reality…And in this way everyday reality is metamorphosed by means of what we would call the imaginative variations that literature works on the real.”

Editor’s note: Emeritus Professor Philip Almond recently published Mary Magdalene: A Cultural History (Cambridge University Press). He will be giving a public lecture on “The Idea of the Magdalene” at St Francis College on Friday 8 September 2023 from 5pm. Visit the St Francis College website to find out more and to register.