Evensong address on Dr Wangari Muta Maathai

Homilies & Addresses

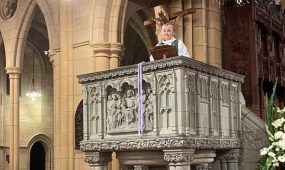

“When invited to offer a reflection in the Cathedral’s ‘Mystics, Theologians and Gob-botherers’ series I thought there was an opportunity for me to better understand the life and legacy of Dr Wangari Muta Maathai, whom I had some sense of as a Kenyan environmentalist, and someone who had inspired many people around the world to plant trees,” said Bishop Cam Venables in his recent St John’s Cathedral address

When it was announced that I was to be ordained a bishop in June 2014, the school that I was working in as a chaplain offered to make the crozier I would carry in subsequent years of ministry. On the wooden staff of this I had engraved the chemical equation for photosynthesis and the names of 40 significant people who have, to a greater or lesser extent, helped to shape my western view of the world.

In that list there are faith leaders, philosophers, theologians, scientists, and politicians…but uncomfortably, only four of those named – just 10 per cent – are women. So, it seems, there has been an unconscious gender bias in the “voices” I have listened to, read, and been shaped by in these areas of human endeavour.

Looking at that list through another lens I recognise that 27 of those voices have some sort of European heritage, six Middle Eastern, four Asian, two American, and just one comes from the continent of Africa. So, again, there has been an unconscious bias, this time a cultural bias, in the “voices” I have listened to, read, and been shaped by in these areas of discipline.

The great problem with gender and cultural biases is that we risk seeing the world while wearing metaphorical blinkers. We see or hear only a narrow portion of the whole and are consequently less aware of the richness, complexity, and hope that can come from the wisdom and experience of those who are culturally and linguistically different to oneself.

When invited to offer a reflection in the Cathedral’s ‘Mystics, Theologians and Gob-botherers’ series I thought there was an opportunity for me to better understand the life and legacy of Dr Wangari Muta Maathai, whom I had some sense of as a Kenyan environmentalist, and someone who had inspired many people around the world to plant trees!

Advertisement

Here is where a gender bias had possibly inhibited me from previously trying to understand Maathai’s work better – because I have been comfortable with the environmental

understanding and insight provided by the Englishman, David Attenborough; the Canadian, David Suzuki; and, the Australian, Tim Flannery. Perhaps there was also a cultural bias in play because I have long admired the work of English primatologist Jane Goodall, and American primatologist Dian Fossey…but, who was Wangari Maathai?

I have tried to better understand this through a number of YouTube interviews with Dr Maathai, and through two books that Dr Mathai authored. They are her autobiography titled, Unbowed, published in 2006, and her last book, titled, Replenishing the Earth, published in 2010.

Wangari Muta Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya, 82 years ago, on April 1 1940. Maathai was born into a Kikuyu family and her father had four wives. Her mother was the second wife and there were 10 children in the household.

In her early years Maathai was educated by three Roman Catholic religious orders: her middle school years were at St Cecilia’s run by the Consolata Missionary Sisters; then the Loreto High School run by the Loreto nuns; before her first round of Tertiary education at Mount St Scholastica Academy in Kansas, run by the Benedictines.

Advertisement

Her familiarity with both Old and New Testament scripture seems to be grounded in these formative years and Maathai draws effectively from both in her teaching about environmental stewardship and social justice.

A good example is her interpretation of the Genesis creation story, and I quote:

“I relate how God in his infinite wisdom, waited until Friday to make human beings, and then rested on Saturday (the Sabbath). If we’d come into existence on Monday, we would have been dead by Tuesday, because there would have been nothing to sustain us!

The writer or writers of the creation story understood that we are at once the culmination of the process of creation, and yet its most dependent creature. We could only be created once everything else – the sun, and moon, the earth and the sea and the air, and all the flora and fauna – had been separated one from another or brought into existence. God could form humans only once there were trees to remove the carbon dioxide from the air and replace it with oxygen, and then balance the composition of the air so that the whole planet did not burst into flame. He understood that in order to eat, we would need pre-existing seeds. It’s a sobering thought that if the human species were to become extinct, no species I know of would die out because we were not there to sustain them. Yet if some of them become extinct, human beings would also die out. That should encourage us to have respect for other forms of life and indeed for all of creation.”

However, before Wangari Maathai was a storyteller she was a scientist who wrote brilliantly about string theory, astronomy, and sustainability in her last book Replenishing the Earth. Maathai earnt a Bachelor of Science from Mount St Scholastica Academy in Atchison, Kansas in 1964; a Master of Science from the University of Pittsburgh in 1966; doctoral research in Munich and Nairobi, before completing a PhD from the University of Nairobi in 1971. Through this Dr Maathai became the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctoral degree – in 1976 becoming chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and an Associate Professor.

While working voluntarily with the Kenyan National Council of Women, Maathai realised that many of the problems faced by women in rural areas came from a progressively denuded environment. In many places soils had become exhausted by cash crops, water was scarce because there was no vegetation to hold it, and firewood used up what few trees were left. The Kenyan Government at the time seemed uninterested in responding to these challenges, so Dr Maathai introduced the idea of community-based tree planting to change the trajectory. Her vision was to create a broad-based grassroots organisation whose main focus was poverty reduction and environmental conservation through the planting of native tree species. Launched in 1977, this Green Belt Movement is now credited by UNESCO with planting more than 50 million trees.

Though initially made up of a small number of community groups, the Green Belt Movement grew steadily to become a network of many thousands of community groups. To maintain the integrity and focus of this work Maathai writes compellingly about the importance of four core values that each group, and each group member, agreed to live by.

Again I think it’s helpful for us to hear Maathai explain these in her own words for they are wisdom gleaned from action, and then reflection upon that action, before further action.

The first is:

“Love for the environment: Such love is demonstrable in one’s own lifestyle. It motivates one to take positive action for the earth, such as plant trees and ensure they survive; nurture those trees that are standing; protect animals and their habitats; conserve the soil; and undertake other such activities that show appreciation in a tangible way for the earth…”

The second is:

“Gratitude and respect for Earth’s resources: This entails valuing all that the earth gives us, and because of that valuation, not wanting to waste any of it, and therefore practicing the three R’s: reduce, reuse, recycle. In Japan, the term used for this is mottainai.”

The third is:

“Self-empowerment and self-betterment: This is the desire to improve one’s life and life circumstances through the spirit of self-reliance, and not wait for someone else to do it for you. It also entails turning away from inertia and self-destructive activities such as addictions. It encompasses the understanding that the power to change is within you, as is the capacity to provide oneself with the inner energy that’s needed.”

And fourthly:

“The spirit of service and volunteerism: This value…means using one’s time, energy and resources to provide service to others, without expecting or demanding compensation, appreciation, or even recognition. It is the giving of self that characterises prophets, saints, and many local heroes…”

The first two of these values clearly resonate with the Fourth Mark of Mission, articulated in our Diocesan Mission, Vision, and Values, work for it affirms we are “to strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth”. However, Wangari Maathai was not awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004 for her environmental work alone, but also for her work on women’s and gender issues, human rights advocacy, and good governance advocacy. Indeed, it appears to have been the first time that the Nobel committee in Stockholm acknowledged the interrelationship of these four areas.

It’s also important to note that two years before being awarded the Nobel Prize, Wangari Maathai was elected as a member of Parliament in 2002 receiving 98 per cent of the vote in her electorate. Maathai then served for almost three years as assistant minister for the environment and natural resources.

Though each of her books quote passages from the Bible, Maathai was clear eyed about the role colonialism had played in replacing traditional Kikuyu cosmology with Christian belief, and in replacing traditional Kenyan food crops with cash crops that have repeatedly exhausted the soil. Maathai argues helpfully that a religion that teaches that the earth is not our home is a religion that will not recognise or prioritise the need for wise environmental stewardship for the sake of future generations and there is an uncomfortable truth in this that could be helpfully explored in discussion.

A sign of hope for her was the role that leaders from many faith traditions played in contributing to the UN sponsored Earth Charter that was launched in the year 2000. If you haven’t heard of The Earth Charter, I encourage you to find it using Google because it offers helpful ways forward when considering the complex environmental, economic, and social challenges we face globally.

The legacy of more than 50 million trees planted is remarkable, but I think the vision Maathai has given of a more just and sustainable world…more so. Maathai then is not a “God botherer” but could be considered a prophet who calls us to do life differently. A theologian who resonated with the Franciscan sense of the created world speaking of the Creator; though in this Maathai often substituted the word “God” with the term “The Source” because the word “God” in her experience was often used to justify colonial power. Maathai could quite possibly be considered a mystic who felt most nourished by “The Source” when in the company of trees looking towards Mount Kenya.

In the final chapter of her book Replenishing the Earth Maathai references the parable of the mustard seed, which began small but grew to became something huge, giving shelter and food to many (Matthew 13.31-32). I think the life of Wangari Muta Maathai was such a seed, and I think we are challenged tonight to learn from her life and wisdom.

Amen

Some questions for further discussion:

- What gender or cultural biases are you willing to recognise in your own life? And, what will you do to change these?

- What did you find most challenging, or inspiring, about the life of Wangari Maathai?

- What elements of Anglican theology reduce the likelihood of us being good stewards of creation?

Aaronic blessing in Ki-Swahili (Numbers 6.24-26)

Bwana akubariki na akulinde

Akuangazie uso wake, na kukufadhili

Akuinulie uso wake

Na kukupa amani

Amina

Editor’s note 9/04/2022: Bishop Cam’s sermon on Dr Wangari Muta Maathai can be viewed on St John’s Cathedral YouTube (fast forward to 49.12 minutes).