Art, faith, justice and Reconciliation

Features

“My Anglican faith feeds into my artistic drive, motivating me to continue to pursue social justice and Reconciliation through my practice and to continue to find ways to adapt in challenging times, such as these,” says local artist, Community of The Way member and Gubbi Gubbi descendent John Hammer in the continuing anglican focus series, ‘How my art intersects with my faith’

Story Timeline

How my art intersects with my faith

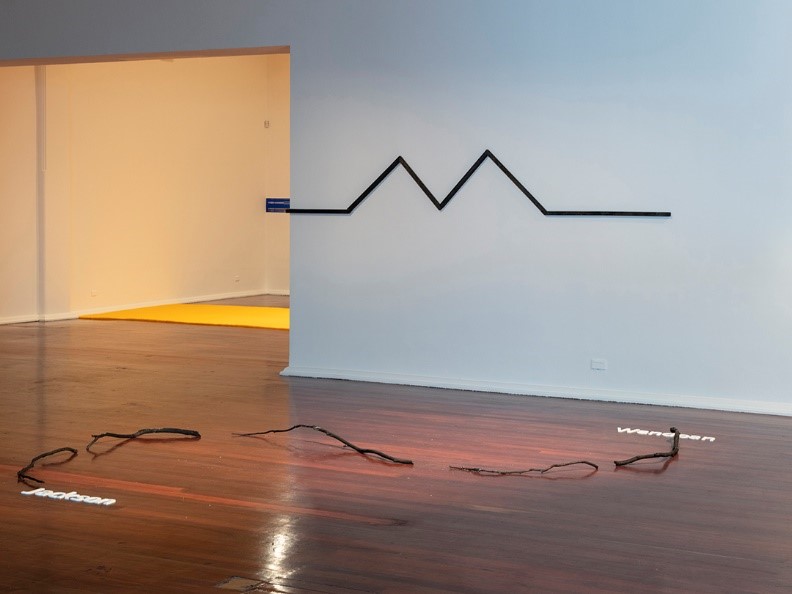

Over the past few years, my practice has focused on issues of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander justice and Reconciliation, critiquing Postcolonial Australia and criticising the coal mining industry, which I articulate through mediums of sculpture, photography and text. Issues of the coal mining industry really started to manifest itself in my practice in 2018 when I visited towns along the Leichhardt Highway and witnessed firsthand how the mining collapse and the Glencore Wandoan Project had affected the towns of Wandoan and Miles. My work Wandoan Flatline (2018-19) examines how Wandoan has significantly declined in population, with Ghost Towns (2018-19) following the road that links Wandoan to the declining town of Jackson.

Ghost Towns and Wandoan Flatline, 2019: charred pinewood, charred wood, acrylic on MDF board. Instillation view: Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (Image by Bo Wong)

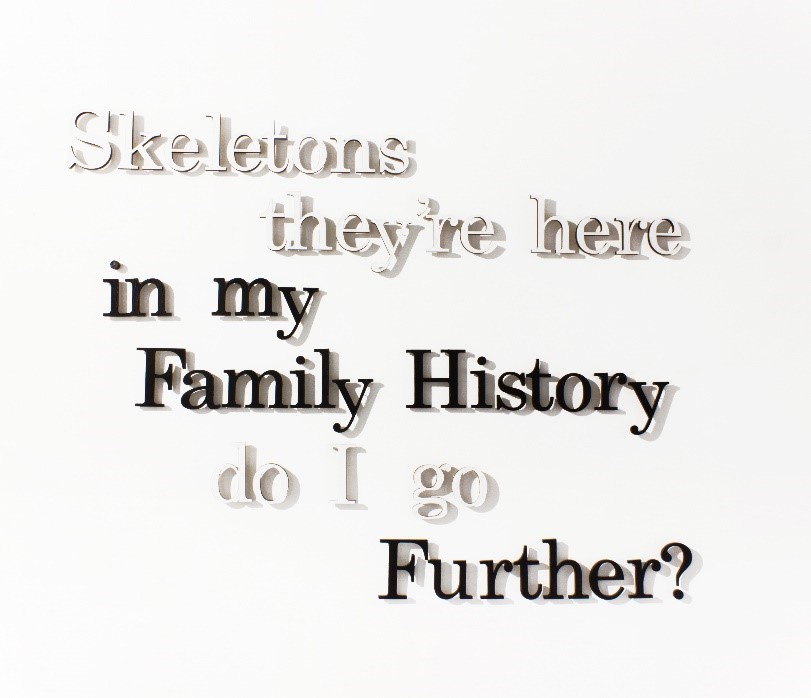

During the same period, I explored Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander justice and Postcolonial Australia. This direction in my practice was shaped by my interactions with my paternal grandfather, who is of Gubbi Gubbi descent. Visiting him out in Yarraman, I learnt about the discrimination and hardships he has endured as a Gubbi Gubbi man. While traveling around the area, I listened to the perspectives of his community members and to their accounts of discrimination and learnt about the history of the area. In these conversations, I found out about the massacre of hundreds of Wakka Wakka men, women and children at Coomba Falls, Maidenwell in the 19th century. My grandfather took me to the site of the massacre. Discovering that a horrific act of butchery had happened in such a beautiful location and learning that there were hundreds of similar massacre sites throughout Australia led me to articulate these stories through my practice and try to educate other people about these sites. Simultaneously, I look at my own family history through a postcolonial lens, coming to terms with the darker aspects of colonialism and striving towards Reconciliation.

II Falls, 2019. Acrylic on charred branches. Displayed at House Conspiracy(Image by Oliver Barker)

Yes, 2018. Acrylic paint on MDF board

My recent work River of Fear (2020) was installed at St John’s Cathedral – a large collection of charred and painted branches that were formed into a river-like composition. The work came to light when St John’s Cathedral commissioned a piece that reflected the recent bushfires and coincided with Ash Wednesday. While I have not had a specifically environmental focus in my practice, I had always accepted that other people were likely to see environmental messages in my work, such as through my use of raw branches. In this work, I arranged branches into a river formation to reflect the way many rivers and creeks turned black as a result of all the ash and debris that were washed into them during the bushfires. The white branches embody what I saw as the government’s inaction towards the bushfires and the attempt to ‘whitewash’ the disaster, despite ample warning from firefighting authorities. Many people lost their homes and much plant life and wildlife perished, with some species of animals and plants at risk of extinction, which is represented by the red branches. Installing the composition outside the traditional white cube gallery space and having it in an unexpected public space, like the Cathedral, helps to confront the viewer with the work’s subject matter and brings issues into the real world and before a broader audience. It was interesting to read through all the responses to this installation on Facebook. While several of the more negative responses were not constructive, I still take a little pride that I was able to challenge the perspectives of such responders enough to elicit comments from them.

“My recent work River of Fear (2020) was installed at St John’s Cathedral – a large collection of charred and painted branches that were formed into a river-like composition. The work came to light when St John’s Cathedral commissioned a piece that reflected the recent bushfires and coincided with Ash Wednesday”

The Cathedral Ash Wednesday bushfire installation was an interesting project and it helped me reflect on my own faith, what it means to be an Anglican and how my faith feeds into my drive as an artist. My Anglican faith feeds into my artistic drive, motivating me to continue to pursue social justice and Reconciliation through my practice and to continue to find ways to adapt in challenging times, such as these. Most of the time, my faith is not in the forefront of my mind while I create my works, but as I reflect more, I see that God is present in myself, the people around me and in every living creature and object. Reflecting in this way helps bring out the best in myself, and in the need to help others around me and my parish by being a Liturgical Assistant and a Parish Council member.

Advertisement

While 2020 is definitely not what I envisioned, with the coronavirus-related restrictions effectively shutting down the creative industries sector, I am still working on some projects that explore some of the colonial history of Brisbane, albeit just by research at the moment. When the COVID-19 challenges pass, I plan on doing a few exhibitions, with one of these featuring The Future was Never (2018), a series of photographs looking into a housing district in Miles, which was abandoned during the mining collapse, as I have regretted not showing these publicly back in 2018. At the end of the year, I plan on submitting my proposal to do a Master of Philosophy (Visual Arts) at Queensland University of Technology. While people shelter in their homes to keep our communities safe, there is still much to look forward to and complete.

Editor’s note: For more information on the work of this gifted emerging artist, please visit John Hammer’s Instagram (@John_Lee_Hammer) or website or email him via johnl.hammerartist@gmail.com