Are Christians pantheists? Well, sort of

Reflections

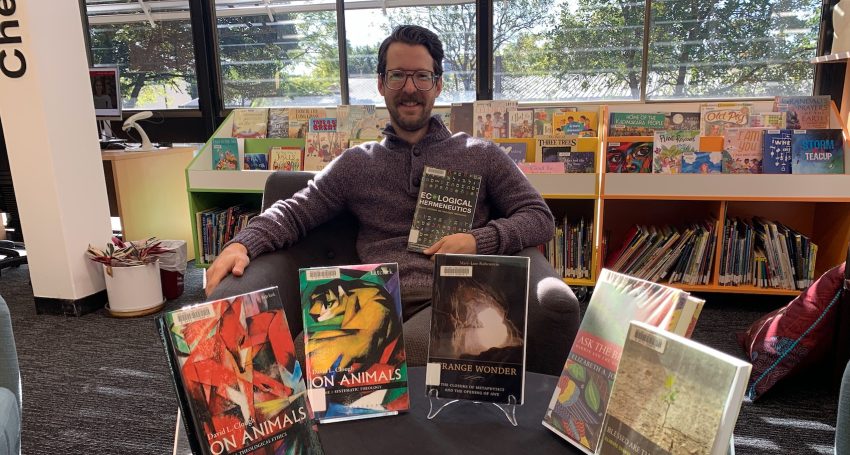

“All creatures, including humans, are divine speech, and what they speak is the eternal goodness and wisdom of God,” says Dr Peter Kline from St Francis College

In these times of mounting ecological vulnerability there are, of course, countless pragmatic exigencies that people who want a liveable planet for their children and grandchildren should engage: the reduction of carbon in the atmosphere, the protection of biodiversity, investment in clean energy, weather-resilient infrastructure, and so on.

However, the resolve required to engage these exigences needs to come from somewhere. We have to want a future for the earth that extends beyond our lifetimes, and that question of wanting, of desire for the good of the earth that we will not be around to see or enjoy pushes us beneath the pragmatic exigencies we face into the realm of whatever sustains (or doesn’t) our engagement with them.

For Christians and folks from other religious traditions, this is the realm of theology and spirituality, which is where we construct, contest, and put into play the imaginations and desires that shape our engagement with the world at a fundamental level.

Over the past half-century or so, an enormous and diverse body of literature called “ecotheology” has emerged that attempts to align the theological and the ecological. Within Christian traditions, several obstacles present themselves on the way toward this alignment. Chief among them is that Christian theology tends to locate the object of highest value—God—outside of the cosmos, which sets the conditions, if not for an outright disparagement of the material conditions of earth-dwelling, then at least for various forms of indifference to it. In the face of this obstacle, eco-theologians construct various visions of the God-cosmos relationship that promote the intrinsic value of the cosmos and of earth-dwelling in particular.

Grace Jantzen, who was a Canadian eco-feminist philosopher of religion, thought that the only way to truly overcome the obstacle of locating our highest values outside of the cosmos was to completely abolish any distinction between God and the cosmos. This is the position known an “pantheism,” which identifies God with the cosmos itself. God is the cosmos, the cosmos is God. The ecological upshot of this identification is that we are given a framework within which to direct our adoration and highest passions toward the cosmos rather than away from it. Typically, Christian theism sharply critiques and distinguishes itself from pantheism, accusing it of idolatry and a deflation of divine sovereignty. If God is everything that exists, then who rules the world? And who will save us?

Advertisement

However, while a distinction between God and the cosmos is an important feature of many dominant “orthodox” Christian theologies, there are what might be called openings toward pantheism that run right through these theologies. These openings remain largely policed by various other theological commitments, but they are nevertheless there, waiting to be re-opened and explored in an age of ecological vulnerability.

One place to look for a version of this pantheistic opening is what is called the “divine ideas” tradition that emerges in early church theologians, such as Augustine, and fully blooms in various medieval theologies. The basic idea of this tradition is that all of the “ideas” of creation, the archetypes or forms for each creature that make it what it is, exist eternally in God as God. The opening of John’s Gospel is central for this tradition: “In the beginning was the Word [God’s ideas for every creature] and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” God’s idea of the Milky Way is God. God’s idea of the elephant is God. God’s idea of Cathy Freeman is God. And so the Milky Way, elephants, and Cathy Freeman, along with every other creature great and small, are all (pan-), in a sense, God (-theism). And God is the all. In his commentary on John’s Gospel, Augustine puts it like this: “Look at the structure of the universe: see what was made by the Word and then you will recognize what the nature of the Word is.” When we look at the universe, we look at God.

As I said, this sort of pantheistic opening is heavily policed. One of the main concepts that keeps this opening from straying from “orthodoxy” is the concept of “analogy”. Creatures are God, but only analogously, only in a sense. Creatures are analogies of God, not directly God. Analogy lets you have your cake and eat it too. It lets theologians put the cosmos into the heart of God, and God into the heart of the cosmos, while nevertheless distinguishing it from God. The universe is God. Well, sort of.

Advertisement

One of the benefits of this tradition, whether one stays with its “orthodox” formulations or follows other heterodox formulations such as those of Nicolaus Cusanus and Baruch Spinoza, is that it animates the cosmos, turning every bit of it into an event of divine communication. All creatures, including humans, are divine speech, and what they speak is the eternal goodness and wisdom of God. Of course, Western theology is rather late on the scene with this sort of claim. Indigenous spiritualities across the globe have always been attuned to the animate, communicative density of the earth and its many creatures. Those of us slow to love the earth in this late hour need teachers older and wiser than our own.

Editor’s note: If you found this feature interesting and you would like to know more about studying at St Francis College or about the Semester 1 2023 subject ‘CT3002/9002: Theology in Context: Ecotheology”, please visit the St Francis College website or contact the Dean of Students, Dr Sheilagh O’Brien, on 07 5514 7403 or via sheilagh.obrien@anglicanchurchsq.org.au