A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

Features

“The noble example set by Catherine of Siena, who recognised Christ in all whom she encountered and bucked social mores by caring for people living with infectious diseases, will hopefully inspire us as our global community experiences health challenges unprecedented in the modern age,” reflects anglican focus Editor Michelle McDonald, as St Catherine’s Feast Day is marked on 29 April

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- The man who would be king

- The saint and the sultan

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

- Hildegard of Bingen

I belonged to a number of intentional faith communities around Australia in the 1990s. One of these intentional communities was an order of missionary nuns who were based in Elizabeth South, a satellite city of Adelaide. The sisters live a rigorous life of prayer and service and possess only the bare necessities, which do not include Uggs, as I discovered when I was gently asked to pack my slippers away soon after I arrived, and to instead help myself to a pair of socks from the communal sock basket.

Among my favourite memories of living with the sisters throughout 1997 was when we gathered for weekly faith formation. The leader of the order, a brilliant, erudite and compassionate Canberra-based priest named Fr Ken, regularly mailed us cassette tapes, each containing an hour-long recording on a range of topics, including scripture, the sacraments, social teaching, contemporary theology, and the lives of mystics and saints.

One cold morning we gathered together to listen to Fr Ken talk about St Catherine of Siena, a lay Dominican, who lived in 14th century Tuscany. I bristled and muttered noticeably in my seat when he described St Catherine as a “manly saint” because of her “tenacity, courage and strength”. When Fr Ken travelled to South Australia to visit us a few months later, I shared that Catherine of Siena is a model of faith, resilience, strength and courage for all people irrespective of gender and politely reminded him that women were equally as capable as men of such virtues. He was incredibly gracious in response, especially given my tender age of 21 and his respective seniority as the order’s Moderator, humbly replying in agreement with my comments and committing to speaking about St Catherine differently in the future.

Catherine of Siena has been an important figure in my faith journey ever since. Upholding her relevance for all people of faith, irrespective of gender, and learning about her contributions as she served as a member of her own intentional community, somehow made her more inspiring to me. Over the 23 years since my conversation with Fr Ken, St Catherine’s relevance in my life has steadily grown.

St Catherine is best known for her reported mystical experiences and manifestations, which began in her childhood; her unusual political achievements and associated travel, especially for a medieval woman who risked her life to broker peace deals between waring Italian states; for chastising popes and monarchs who sought her counsel; and, convincing Pope Gregory XI to move the papal residence back to Rome from Avignon, France.

Advertisement

Despite her remarkable experiences and achievements, I think that St Catherine’s earthy compassion in caring for people who were sick or marginalised and the way she reverently greeted Christ in all whom she encountered are what make her life and legacy most relevant for people of faith today.

Caterina di Benincasa T.O.S.D. was born in the trading city-state of Siena, Tuscany on 25 March 1347 in the midst of The Black Plague, which killed an estimated 25 million people in Europe alone. She was born into a middle-class family and was one of twenty-five children and a twin, although her twin sister Giovanna died soon after they were born. She was the ‘darling’ of the family due to her charm, and reportedly so happy as a child that her family gave her the nickname Euphrosyne, Greek for ‘merry’. She commenced intense prayer and devotional practices around the age of six and vowed not to marry while still a child. Despite violent attempts by her parents, Giacomo and Lapa, to coerce her to marry, the feisty teenager steadfastly refused, wearing rags and cutting her hair in an effort to mar her physical appearance. Notwithstanding her strong religious inclinations and opposition from lay Dominicans, who believed that such a role should be reserved for widowed women and not young virgins, Caterina made the unusual decision to join the mantellate, a group of lay Dominican women, at 16 years of age, rather than a convent.

“In portraits, Catherine of Siena is typically pictured wearing the black and white Dominican habit (in the Middle Ages, habits were typically worn by both lay and consecrated members of religious orders)”

Being part of a lay order afforded Caterina the distinct advantage and freedom of not being confined to a cloister. At the age of 21, after three years of voluntary home seclusion, during which she only left the house for Mass, Caterina is said to have received a vision in which she was told to reenter public life and serve those in her community who were sick, living in poverty or on society’s margins.

Advertisement

Caterina felt called to go beyond the self-imposed cloister of her home and parish, speaking of “the two feet” on which we “must walk” and “the two wings” with which we “must fly to heaven”, these being “love of God and love of neighbour”. For Caterina, lovingly serving Jesus and neighbour were one and the same. My favourite anecdote of her story is that of Caterina saying that we should genuflect to one another in our greetings, recognising that in doing so we greet Christ.

Despite the social stigma associated with illness in her time, when disease was often viewed as a punishment from God for people’s sin, Caterina tirelessly visited unwell people in infirmaries and homes. She cared for those with diseases that were considered repulsive in her day, inspiring many others to do the same.

With her cheerful and tender care, Caterina patiently won over a cantankerous and sharp-tongued poor elderly woman, named Tecca, who was dying in a leprosarium outside the city’s walls. Seeing Christ in a woman that others ostracised, Caterina cleaned and bandaged Tecca’s wounds in her twice daily visits. After Tecca died at peace in Caterina’s arms, Caterina washed and prepared her body for burial.

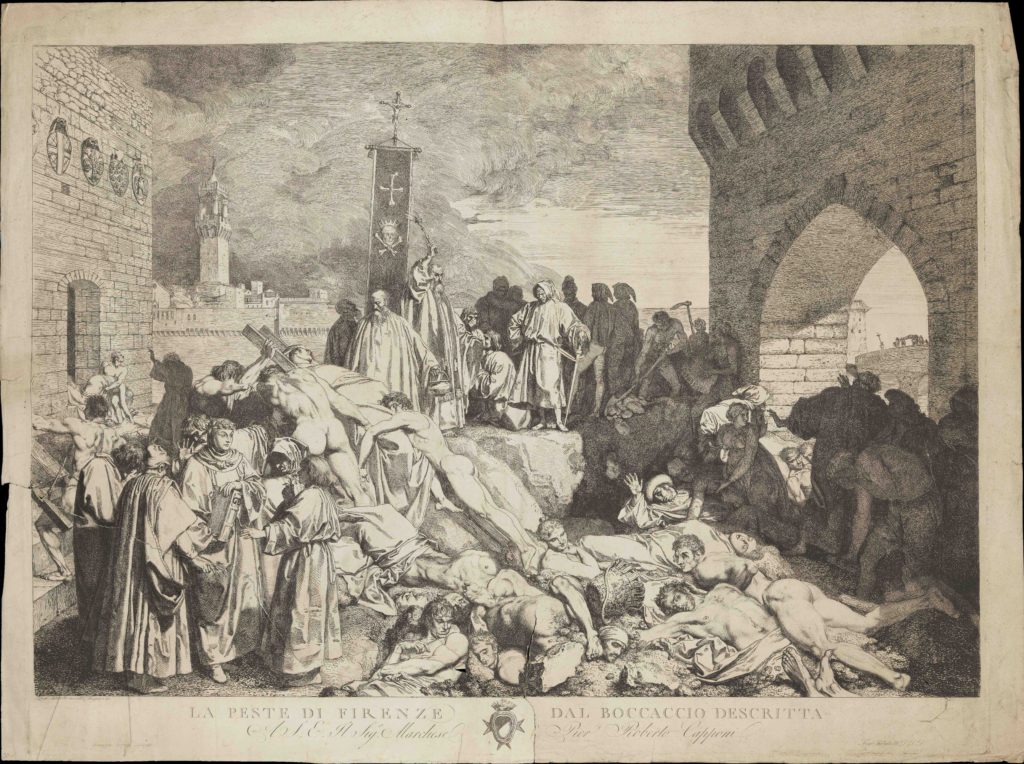

When a plague swept through Siena, many church and civic leaders fled among the rioting; however, Caterina nursed victims and reportedly dug graves herself to give those who died a proper burial.

Boccaccio’s ‘The plague of Florence in 1348’ (This picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence)

She also accompanied prisoners who were condemned to death to the place of execution, walking, waiting and praying with them until the end. One of these was a young man from Perugia, named Niccolo di Toldo, who was sentenced to death for remarks made against the Sienese authorities. Initially refusing to receive any visitors connected with the Church, he relented for Caterina as he was touched by her compassion, with Caterina stating:

“I went to visit him…he was consoled…He made me promise that for the love of God I would be with him at the time of his execution. In the morning before the bell tolled I went to him…I took him to Mass and he received the Eucharist…there remained a fear that he would not be brave at the last moment…I waited at the place of execution in continual prayer…seeing me he laughed and asked me to make the sign of the cross over him…He knelt and stretched out his neck and I bent down over him…”

Tradition has it that Caterina was once approached by a half-naked man who was too poor to afford clothes and freezing in the cold. Breaching social conventions, Caterina did not hesitate to give him her garments.

By 1380 at the age of 33, Caterina became seriously ill, likely due to her austere acetic practice of extreme fasting. She died on 29 April in the same year, just days after experiencing a stroke. Pope Urban VI presided over her funeral, despite Caterina having berated him for his tactlessness and lack of mercy, such that he said, “This little woman is too much for me”. She was buried in Rome’s Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva (Basilica of St Mary over Minerva). Devotion to Catherine of Siena grew rapidly after her death and she was canonised in 1461. Fittingly, St Catherine of Siena is the patron of Italy (together with St Francis of Assisi), nurses and people who are ill. There is also a growing movement to have her named the patroness of the Internet.

Sarcophagus of Saint Catherine of Siena, located beneath the High Altar of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome (This picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 International Licence)

The noble example set by Catherine of Siena, who recognised Christ in all whom she encountered and bucked social mores by caring for people living with infectious diseases, will hopefully inspire us as our global community experiences health challenges unprecedented in the modern age.

In portraits, Catherine of Siena is typically pictured wearing the black and white Dominican habit (in the Middle Ages, habits were usually worn by both lay and consecrated members of religious orders). She is sometimes pictured wearing a crown of thorns, but usually holding lilies (a symbol of purity and devotion) while adoring a crucifix. In images dating back to medieval times, Catherine is also often shown holding a book in her hand. This is unusual given that a book was a common symbol of a saint who had also been deemed a ‘Doctor of the Church’ by the Catholic Church, and St Catherine was not made a Doctor of The Church until 1970 (along with Teresa of Avila).

“She is sometimes pictured wearing a crown of thorns, but usually holding lilies (a symbol of purity and devotion) while adoring a crucifix. In images dating back to medieval times, Catherine is also often shown holding a book in her hand”: ‘Cercle du Maestro de Perea Sainte Catherine de Sienne’ (This picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence)

The legacy of her extensive authorship is published in The Dialogue and in hundreds of letters and dozens of prayers. Caterina’s nearly 400 ‘Letters’ are evidence of the wide audience she reached with her teachings and counsel. While her Letters were primarily written to provide encouragement and spiritual inspiration, she encountered slander and opposition as they began to address more political matters. Charges were laid against her by authorities as a result; however, these were dropped at the Dominican General Chapter of 1374. Her 26 ‘Prayers’ were documented, as it was her habit to pray aloud in the presence of others. Her writings remain relevant today, despite some nuances unavoidably lost in translation and obvious marked theological shifts since the Middle Ages.

Giovanni di Paolo: Saint Catherine of Siena Dictating Her Dialogues (This picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence)

Her writings also serve as spiritual aids in contemplative prayer practice, and are a valuable resource for reflecting on the beauty and interconnectedness of the natural world, the importance of mission and justice, and the God-given uniqueness of each individual:

“Be who God meant you to be and you will set the world on fire.”

“Speak as if you had a million voices. It is silence that kills the world.”

“Nothing great is ever achieved without much enduring.”

“These tiny ants have proceeded from his thought just as much as I. It caused him just as much trouble to create the angels as these animals and the flowers on the trees.”

“Strange that so much suffering is caused because of the misunderstandings of God’s true nature…God’s forgiveness to all, to any thought or act, is more certain than our own being.”

“God is more ready to pardon that we have been to sin.”

“God is closer to us than water is to a fish.”

“What is it you want to change? Your hair, your face, your body? Why? For God is in love with all those things and he might weep when they are gone.”

“We are such value to God that he came to live among us…and to guide us home. He will go to any length to seek us, even to being lifted high upon the cross to draw us back to himself. We can only respond by loving God for his love.”

Which person of faith, living or dead, inspires you the most and why at this time? Please let anglican focus know by emailing focus@anglicanchurchsq.org.au.

The fresco ‘Apotheosis of Saint Catherine’ in the Church of Santa Caterina da Siena a Magnapoli by Luigi Garzi, Rome, Italy

Editor’s note 15 May 2020: On the advice of the Editor’s Greek-speaking uncle and Godfather, James McDonald, ‘Euphrosyn’ was changed to ‘Euphrosyne’.