Martin of Tours: soldier, conscientious objector, hermit and bishop

Features

“St Martin of Tours has a long and celebrated history with chaplaincy – mostly originating from an anecdotal story regarding his cloak, or cappella, from which the word ‘chaplaincy’ is derived,” says Chaplaincy Services Manager Andrea Colledge, as St Martin is commemorated on 11 November

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- The saint and the sultan

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

Since coming to Australia from Canada in 2007, I have been immersed in the chaplaincy space. So naturally, the early Church saint Martin of Tours has been a strong influence on my own ministry. St Martin of Tours has a long and celebrated history with chaplaincy – mostly originating from an anecdotal story regarding his cloak, or cappella, from which the word ‘chaplaincy’ is derived. His life was documented by a contemporary hagiographer, Christian ascetic and lawyer Sulpicius Severus (c.363 – c.420), who knew him personally.

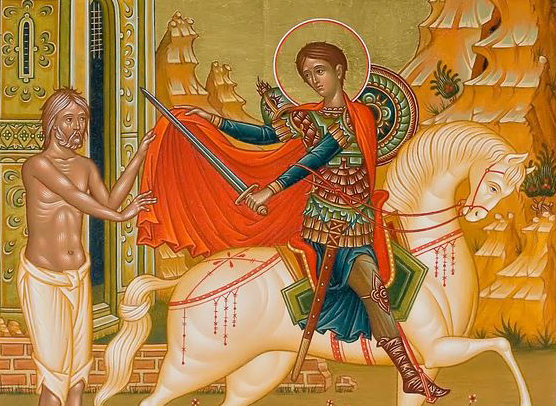

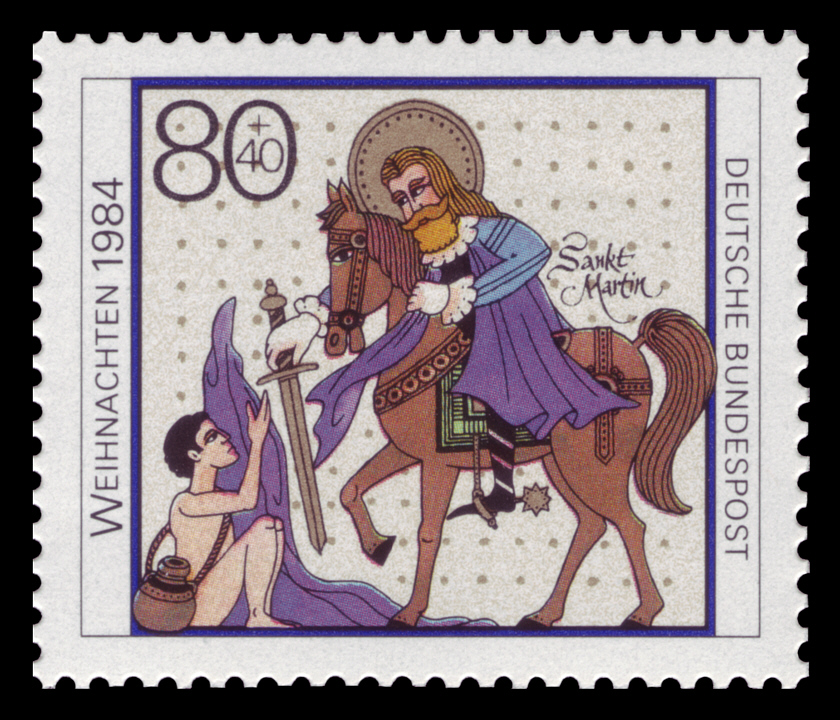

St Martin was a conscripted soldier at the beginning of his career, and legend has it that one day as he was approaching the gates of the city of Amiens in Gaul (France) he encountered a shivering and scantily clad man who was begging. St Martin cut his cloak in half and gave half to the man.

1984 German Christmas stamp featuring ‘St Martin and the beggar’ (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Amiens, France, today

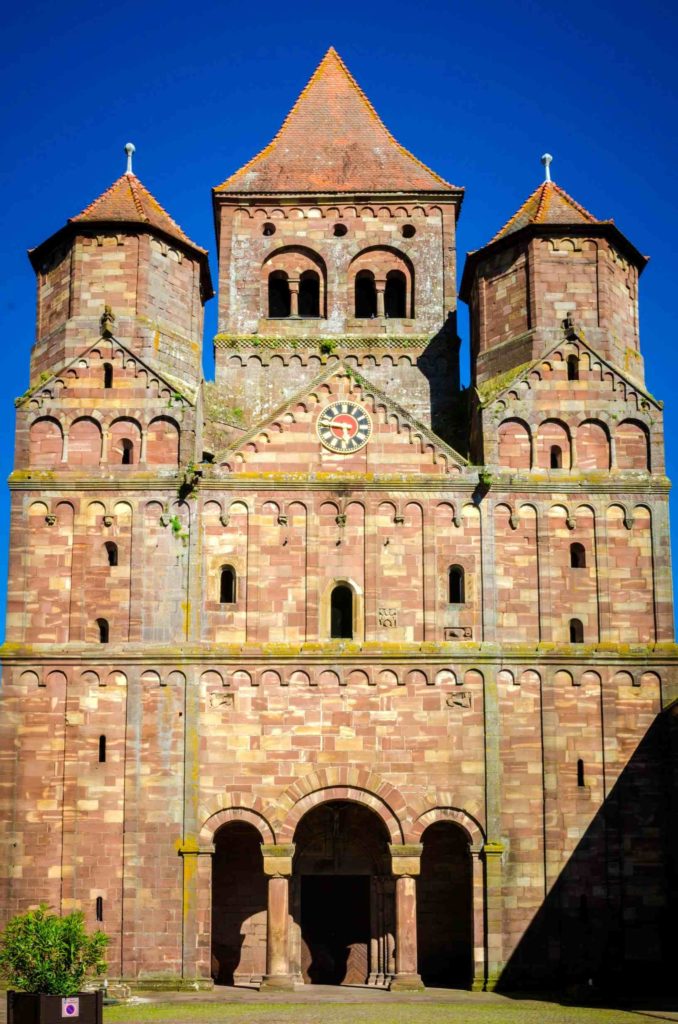

In various tellings, St Martin either had a vision of Jesus telling the angels that “Martin clothed me with this robe” or that when he awoke the next morning he found his robe restored to wholeness. Regardless, half of his cloak became a sacred relic at the Marmoutier Abbey near Tours, was carried into battle by kings and used as a holy object over which oaths were sworn. The priest who cared for the cappella (‘little cloak’) relic was called the cappellanu, and ultimately all priests who served in the military were called cappellani. Thus, the English word ‘chaplain’ is originally derived from the medieval Latin words cappella and capellanus (denoting ‘custodian of the cloak’).

Marmoutier Abbey near Tours

From Sulpicius (not to be confused with Bishop St Sulpicius Severus of Bourges), we know that St Martin was born in either AD 316 or 336 in Savaria, Pannonia (modern day Szombathely, Hungary). The son of a high-ranking military officer, Martin grew up in northern Italy. Against the wishes of his parents, he decided to join the Church at the age of 10 and became a catechumen (a person who is being instructed in the Christian faith). At the age of roughly 15, he was forced to join the military, as was customary for soldiers’ sons in the day, and likely served in the cavalry. The time of his military service is uncertain, with biographers placing it anywhere between two and five years.

Advertisement

Martin is history’s first recorded conscientious objector, declaring that he would no longer fight in combat, reportedly around the age of 20. He petitioned the Roman emperor to be discharged from the military, stating “I am Christ’s soldier: I am not allowed to fight.” In response to being accused of cowardice, Martin offered to go into battle armed only with the sign of the cross. Initially this was seen as the preferred option to jailing him; however, after a brief time in prison, he was released from jail and the military.

After leaving military service, St Martin joined Bishop Hilary of Poitiers, studying under the Bishop until Hilary was forced into exile. After living as a hermit for a time on the island of Gallinaria, where Martin fled as a result of the fall out that occurred from him countering the Arian heresy (which denied Christ’s divinity), he rejoined Hilary upon Hilary’s return from exile.

14th Century depiction of the ordination of Saint Hilary of Poitiers (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

In approximately AD 360 Martin laid the foundations of what would become the Benedictine Abbey of Ligugé, the oldest known abbey in Europe. For a time, St Martin travelled and preached throughout western Gaul. In AD 371 he was reluctantly named the Bishop of Tours. Lured to Tours by a ruse (he was asked to come and minister to a woman who was ill) and consequently found hiding, he allowed himself to be made Bishop. One story states that he hid in a barn full of geese until the cackling gave him away!

Benedictine Abbey of Ligugé (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

As a Bishop, St Martin vigorously dedicated himself to the demolition of all pagan structures. Legend has it that a group of pagans agreed to cut down a sacred pine tree if Martin agreed to stand directly in the path of its felling. He agreed and after making the sign of the cross, the tree miraculously missed him. The story goes that many pagan followers converted to Christianity as a result.

Advertisement

As Bishop of Tours he established over 3,500 churches, visiting each of his parishes annually on foot or by donkey or sea vessel. He also continued to set up monastic communities.

He dedicated himself to the freeing of prisoners so robustly that when authorities heard he was coming, they refused to grant him an audience because they knew that they would be unable to refuse his requests to grant mercy to the prisoners. He also controversially opposed the death sentence for heretics, even standing up to the emperor and advocating for the life of the heretic leader Priscillian. After a lifetime of championing the ‘underdog’, particularly prisoners, St Martin died in 397 in Candes, Gaul.

St Martin is the patron of soldiers, conscientious objectors and tailors, among others. In artistic works, St Martin is often depicted as a soldier on horseback, cutting his cloak for a man who is begging or with a flock of geese, recalling the story of his reluctant election as Bishop of Tours.

St Martin is often depicted with a geese, recalling the story of his reluctant election as Bishop of Tours

The story of St Martin resonates with me on a number of levels. First and foremost are his devotion to God and Christian principles, regardless of his initial occupation. Coming into the Church as clergy or vocational laity after a career outside the Church is quite common nowadays, and it is heartening to know that this is not a new idea. Further in my work with prison chaplains, I see in them what motivated St Martin of Tours – a dedication to people who are vulnerable and incarcerated and to those facing the consequences of their mistakes.

His life story is relevant to Anglicans, as we are all called into a life of compassion, dedicated to the principles of Christianity wherever our occupations may lead us. I hope that the values of St Martin of Tours continue to inspire and pervade the Church worldwide.

St Martin of Tours Anglican Church, Tara, Queensland