A Queensland army chaplain’s war-time diary

Features

“Due to a generous donation of records and materials to the Records and Archives Centre, particularly a detailed diary of his time spent at the Front in the First World War, one war-time Chaplain stands out – The Rev’d Canon Cecil Edwards,” says Archives Researcher Adrian Gibb

As we celebrate Anzac Day this year, born of the sacrifice and bravery of so many, it is important that we, as a Diocese, remember those who have supported our servicemen and women, our chaplains.

Due to a generous donation of records and materials to the Records and Archives Centre, particularly a detailed diary of his time spent at the Front in the First World War, one war-time Chaplain stands out – The Rev’d Canon Cecil Edwards.

Chaplain Edwards (seated, second from left) taken at the Front in c.1916 (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

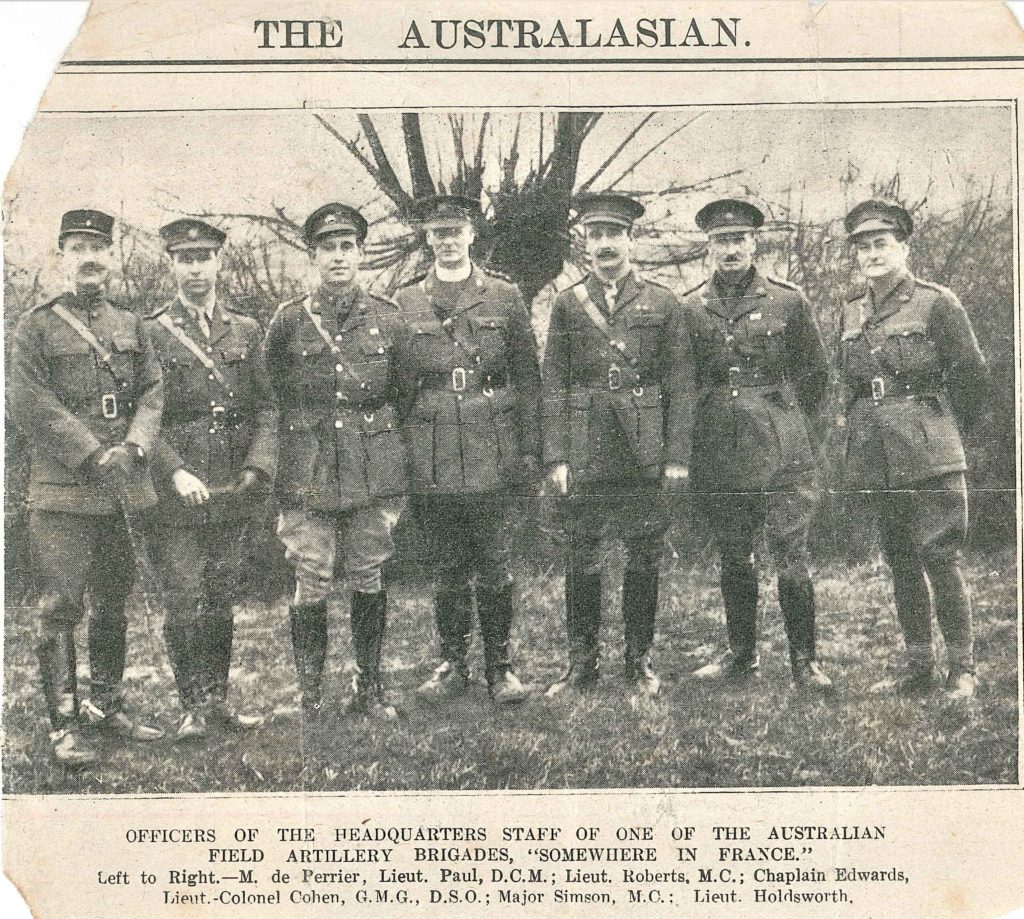

Chaplain Edwards (centre) with Officers attached to the 6th Army Brigade, Australian Field Artillery in c.1918 (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

Cecil Edwards was born in 1877 in England. As a young man, the lure of Australia brought him first to Sydney, and then to North Queensland. By 1905 he had taken up a position as a lay reader, and in 1908 began training at St Francis College for the priesthood. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1910 and almost immediately joined the Bush Brotherhood, becoming the Curate at All Saints’, Charleville. His final posting before the start of the First World War was as Rector of Holy Trinity, Woolloongabba.

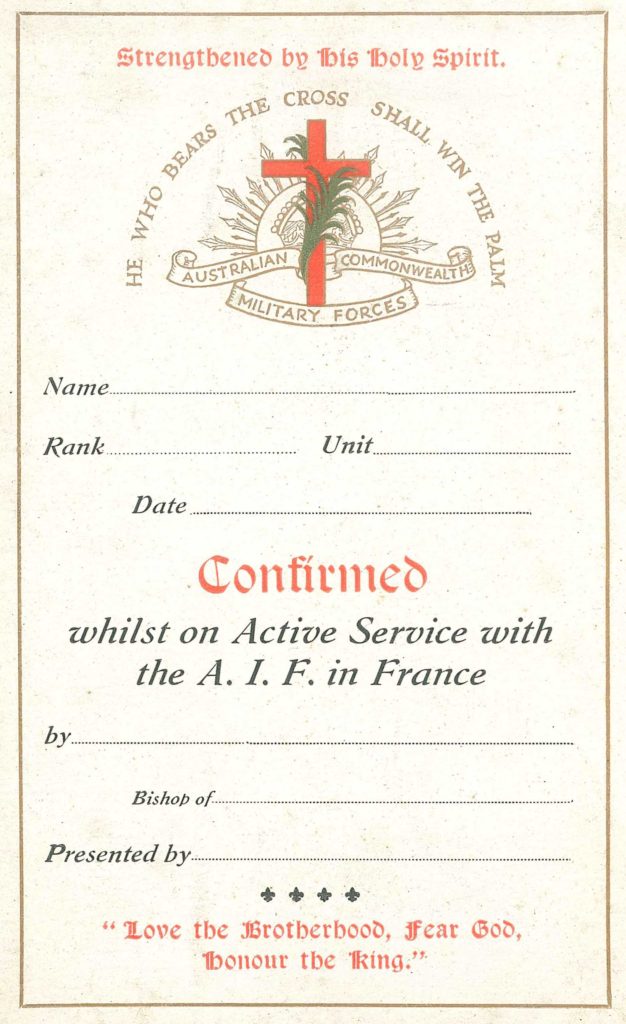

As Cecil Edwards stayed a Bush Brother his entire life, we were fortunate to receive many items from his estate when he passed away in 1965. Many of these items were from his time on troopships and at the front during the war. These included stoles that he used when conducting services, spare confirmation cards that he would have issued to the troops, a black Beretta, currency used during his time in Europe, and even his service medals and ribbons.

The Rev’d Cecil Edwards’ medals and ribbons, left to the Diocese (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

Two stoles used by The Rev’d Cecil Edwards during the First World War (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

A spare confirmation card that would have been distributed by Chaplain Edwards at the Front and on troopships upon a soldier’s confirmation (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

Perhaps the prize possession we received, however, was the diary that Chaplain Edwards kept during his war-time service. Beginning on Friday 24 September 1915, and ending with the words, “My last day of military furlough” on 10 January 1920, his words give us an extraordinary insight into what life must have been like for the priests who served as chaplains during those dark days.

In 2016, as a part of the grant the Records and Archives Centre received to detail First World War Chaplains, the diary was transcribed by then Archives Volunteer Grace Howell.

The war-time diary of The Rev’d Cecil Edwards – 1915-1919 (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

The diary begins with an account of the journey from Australia on the troopship, Argyllshire. Unfortunately, for many of those who cheered and hooted when the ship left, the ravaging effects of sea sickness soon took their toll, not only on their bodily constitutions, but also, as is evidenced in Edwards’ diary, on Church attendance:

“Sunday 3rd Oct-r. [1915]

Wind freshened during night. Frequent rain. Heavy seas. Prepared for early celebration in Saloon Lounge – but no one turned up. Many laid out with sea sickness. Church Parade cancelled – impossible to hold owing to weather conditions. Visited all the decks + felt rather squeamish. Wind + sea increased. Hospital filled with patients mostly sea sick, one mumps, two diphtheria suspects. Felt too seedy for Evensong + doubt if it would have been acceptable. No place on board for private gatherings. This will be a great disadvantage in getting hold of the lads. Consider probability of having celebration in one of the decks each morning, but can do nothing till the weather moderates. A disappointing Sunday from Chaplains’ point of view. Bad weather increases fore troop deck flooded. Adjutant seems most obliging + good sort.”

Advertisement

Even as they made their way over the ocean, Edwards was starting to dread what was to come:

“Saturday 9th [October, 1915]

Running into bad weather again. Not looking promising for services tomorrow. The young officers are a very fine lot of men – physically + otherwise. Full of fun + frolic. Lt Blake is a born comedian + is splendid at comic songs. It is dreadful to contemplate their being killed + wounded.”

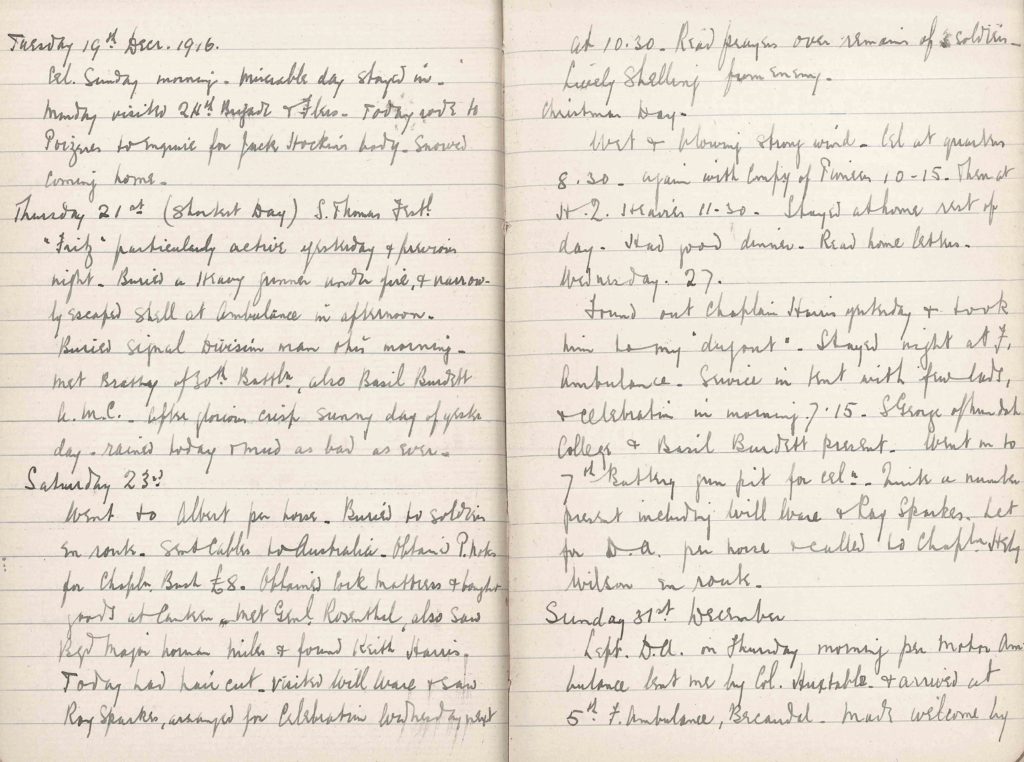

As one goes through the diary, however, the most remarkable thing is the juxtaposition between the deprivations and tragedy of war, and the ability of Edwards to remain focused on doing his job, and, to a degree living his life, to cope. A prime example of this can be seen in entries made just before Christmas in that horrific year of 1916, not long after the Battle of the Somme ended. Here he describes what seems to be horrific conditions, narrowly escaping being hit by a shell, the burial of many men in a single day, alongside mundane, even routine tasks, like sending cables back home, visiting the canteen, and even getting a haircut:

“Thursday 21st (Shortest day) S Thomas Festival [December, 1916]

‘Fritz’ particularly active yesterday + previous night. Buried a Heavy gunner under fire, + narrowly escaped shell at Ambulance in afternoon. Buried Signal Division man this morning. Met [Brethy] of 30th Battalion, also Basil Burdett A.M.C. After glorious crisp sunny day of yesterday, rained today + mud as bad as ever.”

“Saturday 23rd. [December, 1916]

Went to Albert per horse. Buried 10 soldiers en route. Sent cables to Australia. Obtained [?] for Chaplain Bush £8. Obtained [?] mattresses + bought goods at Canteen. Met General Rosenthal, also saw Brigadier Major Norman Miles + found Keith Harris. Today had haircut. Visited Will Ware + saw Roy Sparks. Arranged for Celebration Wednesday night at 10.30. Read prayers over remains of 3 soldiers. Lively shelling from enemy.”

Entries for December 1916 in The Rev’d Cecil Edwards’ diary (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

As for the Gallipoli Campaign, which lasted from February 1915 to January 1916, Edwards was more than aware of the consequences. In November of 1915 he reports that soldiers have been informing him that, “…it seems a most undesirable spot to go to.” By December of 1915, Edwards was seeing firsthand the results of the push against the Turks. Again, he relates the horrors of war in his diary:

“Monday 6th. [December, 1915]

Learn that a number of cases that came forward in the train yesterday are frost bite from Gallipoli, + that with some it will mean amputation of feet or hands.”

The following day, Edwards wrote:

“Tuesday 7 [December, 1915]

Took part in cricket match. Missed two catches. Had interesting talk with Sergt Major who has been over at Gallipoli + wounded in 8 places.”

Chaplain Edwards (seated, far right) with other officers and chaplain at the front in c.1918-1919 (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

His resolve to continue with sacramental life was unshaking. It seems that nothing was going to keep Chaplain Edwards from carrying out his duties ministering to the troops.

“Sunday 30th September 1917.

Heard through Hughie Webb that Norman Waraker was killed in recent battle. Had busy week. Several funerals. Visited batteries [artillery units]. Continued daily celebrations. C.O. of 12th took over Group. Glorious weather. Cold at nights. Read several letters from Australia.”

Advertisement

“Sunday 21st October 1917.

Today had Eucharist Parade in Y.M.C.A. Hut with 12th Brigade + service in Church Army Church with 6th Brigade. Hymn Service in hut in camp in evening.

Whilst in rest visited batteries of 6th Brigade + had a talk to lads. Confirmation arranged for 24th cancelled owing to orders to move. Shifted camp on Thursday 18th instant. Difficult hill to negotiate. Comfortable quarters at Reninghelst. Bomb killed 5 + wounded 3 lads in 45th Battery on night of 19th instant. Very cold at nights. Rain began Monday morning.”

Despite the struggles and the hardships that Edwards endured during his time at the Front, he was remarkably lucky in being able, from time to time, to have leave from the rigors of the trenches. He would use this leave to go across to England, and see his extended family, more often than not his Aunt Jane, whom he called Janie. It was while on such a spell of leave in London that he heard the news that the War was over:

“Monday 11th 1918.

Armistice signed. In town with Janie. London gone mad. Lunch at the Ritz. King + Queen passed on way to S Paul’s. We attended. Poor service. In town again at night.”

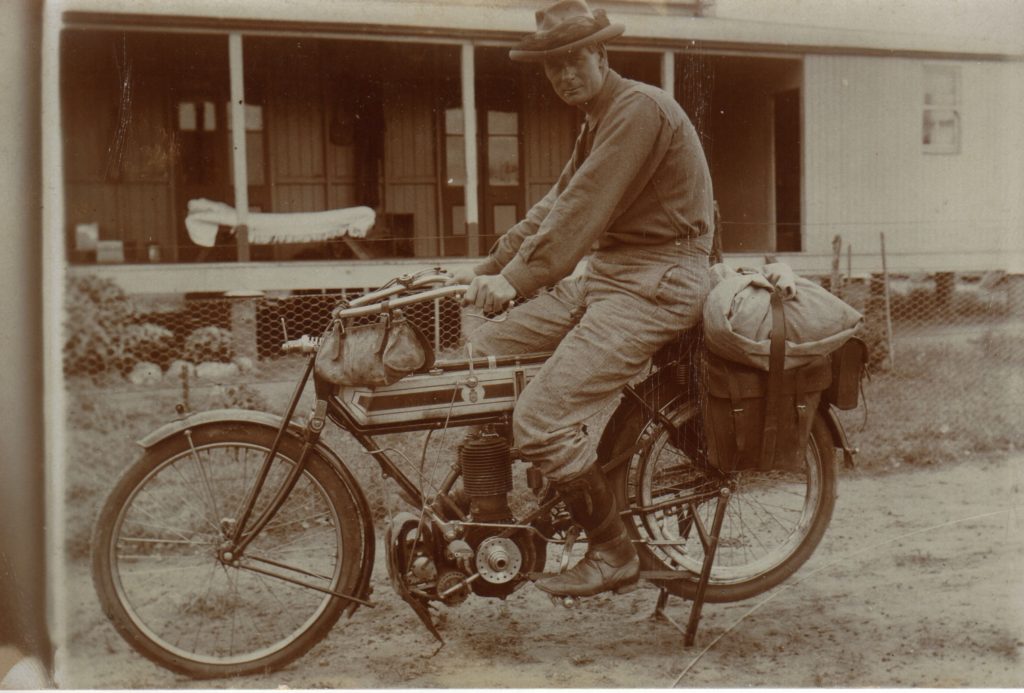

Before his time overseas was finished, Chaplain Edwards decided to purchase a motorbike, perhaps because he had seen how useful they had been during the war. He took this back with him to Australia, and it was an incredibly helpful tool to cover large distances, particularly when he took over as head of the Bush Brotherhood and Rector of All Saints’, Charleville in 1927.

The Rev’d Cecil Edwards on his motorbike as a Bush Brother in c.1925 (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

From Charleville he went on to become a school chaplain to an Anglican School, even funding the school with his own money for a few years until it became viable in its own right.

In 1934 Edwards was made an Honorary Canon of St. John’s Cathedral. His years with the Bush Brotherhood, alongside his war-time service, were very special to him. In the Bush Notes for 1957, Canon Cecil Edwards speaks alarmingly of a wedding he attended as Bush Brother along the Maranoa River, opposite Dunkeld Station:

“The river was in flood and we had to swim the horses over, I had come from the other side of Charleville by train and horse. On arrival at the house I could hear screams of ‘I won’t, I won’t’. The mother of the bride came out and told me that the bride was excited. If I could come back in an hour she would have her quietened down.”

While it is unclear why the bride was so upset, he goes on to relate that the marriage was a happy one, with many children, including two sets of twins, and that the bride became a staunch worker for the church.

In the book Brothers in the Sun: A history of the Bush Brotherhood Movement in the Outback of Australia by R.A.F. Webb, the above episode is described, as is another where, at a remote homestead west of Cunnamulla, Brother Edwards was trying to get a group of bewildered children to kneel and pray. In desperation, he reverted to the word he had heard said to camels when one wanted them to kneel and cried, “Hooshta!” Sure enough, the children knelt and he subsequently led them in devotions.

Related Story

Features

Features

Sister Ella McLean: Queenslander, Anglican and WWI nurse

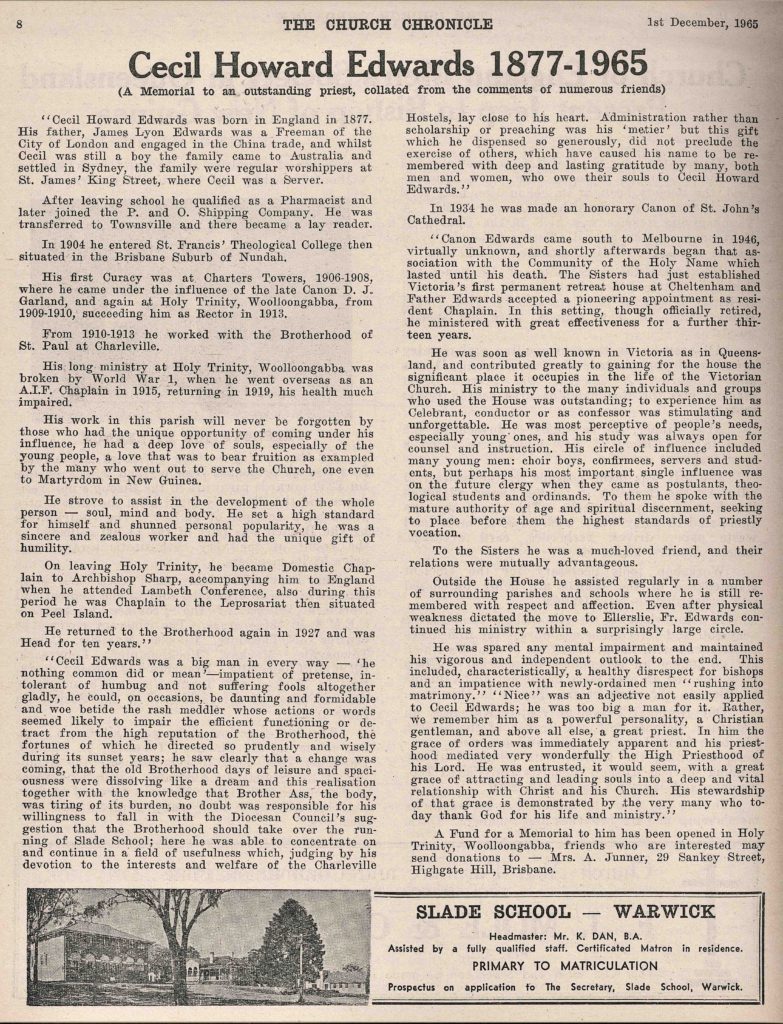

Canon Edwards retired to Melbourne in 1946 and died in 1965. In his obituary, published in The Church Chronicle in 1965, is a collation of comments from numerous friends. He is described as being a big man who didn’t suffer fools gladly, and who could be “daunting and formidable”. However, he was also described as a person who had a “deep love for souls”, as well as being “a Christian gentleman, and above all else, a great priest”. Perhaps his personality could be summed up, however, in this brief passage:

“He strove to assist in the development of the whole person – soul, mind and body. He set a high standard for himself and shunned personal popularity, he was a sincere and zealous worker and had the unique gift of humility.”

Obituary for The Rev’d Canon Cecil Edwards in the 1 December 1965 Church Chronicle (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre – ACSQ)

In Cecil Edwards we can see, perhaps, expectations become reality. He is what we hope a war-time Chaplain would be. With his cool demeanour, his casual resolve, but, more importantly, his steadfast courage in the face of death and his complete resoluteness to act in his pastoral role to the Australian troops, we can see Chaplain Edwards as an exemplar, one which many other Chaplains have also embodied.