Gender-Balanced Belief: A New Ethic for Christianity

Books & Guides

“Reading this book has brought back memories of how we in the Movement for the Ordination of Women in the Anglican Church of Australia were joined by Catholic, Orthodox and Lutheran women and men, and others, to support our struggle for women’s ordination in the 1980s and 90s,” says Dr Gwenneth Roberts, trailblazing ordination of women campaigner

Story Timeline

Trailblazing Australian Anglicans

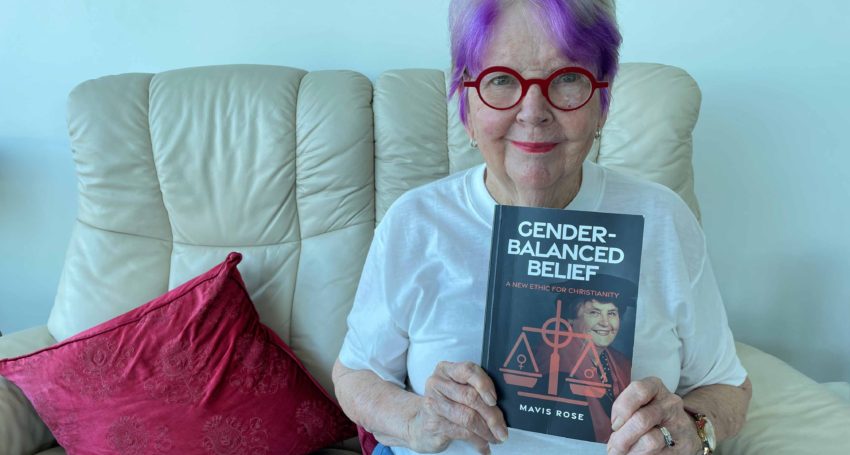

Mavis Rose’s posthumously published book Gender-Balanced Belief: A New Ethic for Christianity is a sequel to her first book, Freedom from Sanctified Sexism: Women Transforming the Church, which was a history of women in the Anglican Church of Australia.

In her first book, which was published in 1996, she revisited her doctoral thesis – that the subordination of women that has existed for two millennia still exists in patriarchal mainstream churches. In Gender-Balanced Belief, the author widens the scope to critique other mainstream Christian denominations, notably the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches. At the core of her belief is that Jesus Christ is a relevant and vibrant role model for the new millennium. She emphasises that Church women who are questioning the subordinate role of women in the Church are not mounting resistance against the true God nor denying the leadership of Jesus Christ (p.187).

The author’s posthumous book covers Church history to 2010, so the reader needs to consider changes in the last 11 years. In the 1980s and 90s feminist theology was considered the foremost contemporary progressive theology. A survey of seminaries and theological colleges would ascertain how many of those institutions still teach feminist theology courses, whether what is being taught has changed or whether interest has waned. However, fresh signs of life have emerged with the formation of the Australian Collaborators in Feminist Theologies network, supported by the University of Divinity in Melbourne.

In her ‘Introduction’, The Rev’d Dr Josephine Inkpin considers that, “conflicts over sexuality and its control have…taken over from female-specific issues at the centre of much debate and wrestling for power and liberation” (p.vi). Inkpin considers that Mavis Rose’s words do not incorporate all aspects of contemporary intersectional feminist struggle, but do powerfully affirm the need for shared understanding and common action.

Mavis Rose substantiates her critique of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches through her dialogue with women from these Churches whom she knew as prominent supporters of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) in the Anglican Church. She calls this “ecumenical solidarity”, and quotes notable Australian Christian women scholars, including Sister of Mercy Professor Elaine Wainwright RSM (p.183); the late Dr Marie-Louise Uhr, a biochemist and Roman Catholic lay woman and former Vice President of MOW (p.140); and, Dr Leonie Liveris, a historian and Greek Orthodox woman and MOW member (p.96).

Advertisement

Mavis Rose follows a process of construction and deconstruction in relation to the position of women in the Church. She looks effectively to the teachings of Jesus, and how He treated women of His time with equality, respect and dignity, which was counter-cultural in patriarchal Roman imperial society. She considers that He subverted conventional wisdom where He saw it to be no longer relevant and was often in a state of contention with the religious hierarchy of the day. For example, Jesus challenged bodily taboos of his era – for example, by holding the hand of Simon Peter’s mother-in-law who was unwell with a fever (Mark 1.29-31) and by healing a woman with menstrual problems (Mark 5.24-34) (p.127).

Jesus’ teachings and example serve as a model for the faithful to be vigilant and unafraid of dissent (p.137). The author understands well the cost of dissent, as she told me in conversation that she was labelled “the black sheep” by some in the Diocese of Brisbane in the 1980s for her forthright public position on the priesting of women.

Scripture records the leadership of prominent women in the early Church. Paul spoke of his women co-workers and acknowledged Junia as “foremost among the apostles” (Romans 16.7, p.142). Recent reconstruction of Mary Magdalene sees her as “the apostle to the apostles” rather than merely as a repentant prostitute (Bourgeault 2010, p.73).

Advertisement

Most of the deconstruction of Christianity in relation to women’s place in the Church follows the formation of State religion in the 4th century. The author traces dualism in Graeco-Roman thought which State religion adopted – male/female bodies and soul/body, among many others. By the 6th century, women typically only found leadership in convents. Dualism which pervaded early Christianity still finds it place today in sexism in the ecclesiastical structures of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches (p.69).

History typically concentrates on the male Christian ‘greats’, such as Augustine and Aquinas, who believed that women were by virtue of their nature in a state of subjection. Even the Reformers Luther and Calvin did little to enhance women’s status, relegating women to marriage and domesticity. The author describes aspects of their writings about women that perhaps we have not known (p.32). She quotes what some consider incorrect exegesis of scripture from Luther, using the second chapter of Genesis as a basis for the earthly subordination of women (p.32) (Miles, 1991).

Women were largely written out of history for a time. German abbess and polymath Hildegard of Bingen (12th century) and English anchorite and theologian Julian of Norwich (13-14th century) were women of outstanding intelligence who have only recently been rediscovered (p.106).

We note in our current Brisbane Diocese Anglican women’s history exhibition, From Biscuits to Bishops, that there is little record, text or photos of 19th century Anglican women who were fundraisers for new churches and were often unacknowledged.

The author devotes a large part of her book to the devaluation of women in the Church, including the embodiment of the Virgin Mary as the ideal Christian woman, which had no increased status for women (p.103); the demonisation of so-called ‘witches’ in the 15th century (p.116); and, the biological supposition that only men were progenitors, which was debunked by the discovery of women’s ovaries in the 17th century (p.81).

The author also acknowledges the clash of colonial culture and Christian beliefs with First Nation spiritualities (p.152). She acknowledges the work of Bidjara / Kari Kari woman, Dr Anne Pattel-Gray, but omits Anne’s criticism of Christian feminists whom First Nations women believe they were excluded by (Pattel-Gray, 1995).

Reading this book has brought back memories of how we in the Movement for the Ordination of Women in the Anglican Church of Australia were joined by Catholic, Orthodox and Lutheran women and men, and others, to support our struggle for women’s ordination in the 1980s and 90s.

As an Anglican woman, I believe that we cannot rest on our laurels for the equality we have achieved, but enquire of our Catholic and Orthodox sisters what we can do to assist them, and indeed for the laity of other denominations who have a minimal voice in the structures of their respective Churches. I observe, for example, that many Catholic women are hurting and angry at their ongoing treatment by their very centralised Church, such that many women just leave.

I consider this book, written by an Anglican woman, with its scholarly and Biblical approach will be acceptable, encouraging and affirming for Roman Catholic and Orthodox women to read. It is also useful for Christians of all denominations to expand our ecumenical dimensions regarding the position of women in the wider Churches.

Bourgeault, C. 2010. The Meaning of Mary Magdalene: Discovering the Woman at the Heart of Christianity. Shambhala Publications, Boston, Massachusetts.

Miles, MM. 1991. ‘Lectures in Genesis’, in Carnal knowing. Vintage Books, New York, pp.107-109

Pattel-Gray, A. 1995. ‘Not yet Tiddas: An Aboriginal Womanist Critique of Australian Church Feminism’, in M Confoy, D Lee, and J Nowotny, Freedom and Entrapment: Women thinking theology. Dove, North Blackburn, pp.165-192.

Rose, M. 1996. Freedom from sanctified sexism: Women transforming the Church. Allira publication, MacGregor, Queensland.

Mavis Rose, 2021. Gender-Balanced Belief: A New Ethic for Christianity. Coventry Press, Melbourne.

Mavis Rose’s book Gender-Balanced Belief: A New Ethic for Christianity will be launched following Evensong on Sunday 23 May at 6 pm at St John’s Cathedral. The Rev’d Dr Josephine Inkpin will preach at Evensong, and launch the book at 7 pm. The book will be on sale at the Cathedral Book Shop. Visit Facebook for more information (including Zoom information to join in the post-service discussion) and the Cathedral’s YouTube channel for live steaming of the event.