Church war memorials: our Diocese’s legacy

Dates & Seasons

“Erecting memorials after World War I was one way of helping people come to terms with their grief, as well as expressing gratitude for the sacrifice and courage of the Diggers who served. The size of the monument at the Ma Ma Creek church reflects the sheer scale of loss experienced by one local Anglican family, the Andrews family,” says Denzil Scrivens from St John’s Cathedral

Thirteen kilometres south west of Gatton on the Gatton-Clifton Road one drives through the tiny rural town of Ma Ma Creek. As you pass through this isolated spot, a completely unexpected site appears – the old Anglican church of St Stephen’s surrounded by bushland. Next to it is the church’s modest graveyard. At first sight, both the church and the graveyard appear ordinary.

However, dominating the churchyard is a life-size statue of a First World War soldier, a “Digger”, standing atop a massive plinth. His head is bowed and his hands rest on a reversed rifle. The memorial is the focus of local public Anzac Day memorial services.

The size and quality of this impressive monument are what one would normally expect to find in a city park or cenotaph. To find something of this nature in an isolated rural district town is at first quite astonishing. Yet on deeper reflection, it’s unsurprising.

After the Great War, the practice of erecting memorials was commonplace in Queensland, as it was elsewhere in Australia. Whole communities were traumatised. Many family members, friends and associates had been killed or injured in the fighting. Almost everyone knew someone who had experienced the death of a loved one.

Erecting memorials after World War I was one way of helping people come to terms with their grief, as well as expressing gratitude for the sacrifice and courage of the Diggers who served.

The size of the monument at the Ma Ma Creek church reflects the sheer scale of loss experienced by one local Anglican family, the Andrews family. Fleurine Andrews was widowed in 1907 and left to care for her family of eight boys and three girls on the family farm.

Advertisement

When war broke out, three of her sons, James, George and Bertie, enlisted. All were killed in France. James was killed in 1916, aged 26. George, Fleurine’s eldest son, was killed in 1917, aged 28. Her youngest boy, Bertie, died in 1918, aged 20.

With the help of local community donations, Mrs Andrews commissioned the monument in 1919, a year after Bertie’s death. The Queensland Government website notes that the memorial “is a rarity, the only surviving ‘Digger’ wearing a cap instead of a slouch hat.” Mrs Andrews also donated a church organ in her sons’ memory. She died in 1938, aged 80, and is buried beside her husband David in the Andrews family burial plot in the churchyard close to the memorial.

This memorial illustrates how people who lost loved ones in the war needed tangible symbols of remembrance, as well as how often Great War memorials were erected in churches or churchyards. This is also true of memorials erected after World War II.

At the time of both world wars, churchgoing and church association were common. The local church was a key gathering place in the community and a natural centre for commemoration. Anglican churches were a particular focal point because in the first half of the 20th century almost 50 per cent of Queenslanders identified as belonging to the Church of England. There were also historic links between the Anglican Church and the Defence Force community going back centuries.

Advertisement

After the Great War, memorials erected in churches across Queensland were quite diverse. Stained-glass windows were common, as were plaques, honour boards, and the installation of church furniture with brass plaques. Sometimes an entire church was designated as a memorial, as in the case of St Augustine’s, Hamilton.

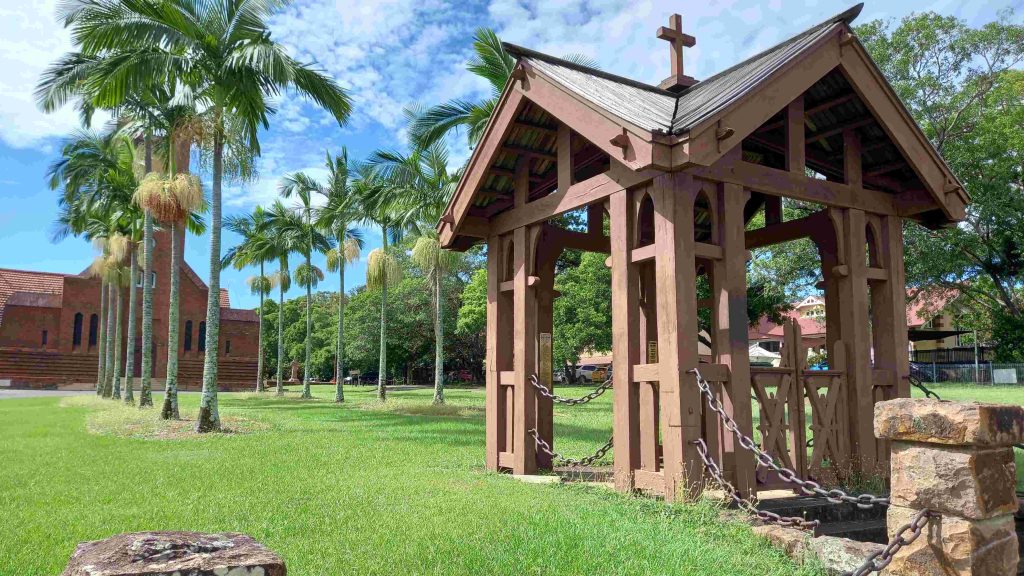

In our Diocese another church with an unusual memorial is St Andrew’s in Lutwyche. The parish lost a devastating 48 men in the Great War, so the surviving men of the parish spent their Saturday afternoons building an impressive timber lychgate at the church grounds’ entrance in memory of those who died. Lychgates are common in medieval English churches, but rare in Australia. The Lutwyche gate was dedicated by Archbishop Gerald Sharp in 1924.

“In our Diocese another church with an unusual memorial is St Andrew’s in Lutwyche (Denzil Scrivens on the church’s lychgate)

St John’s Cathedral has about a dozen war memorials, several of which were installed after the Great War, including the last flag flown at Gallipoli.

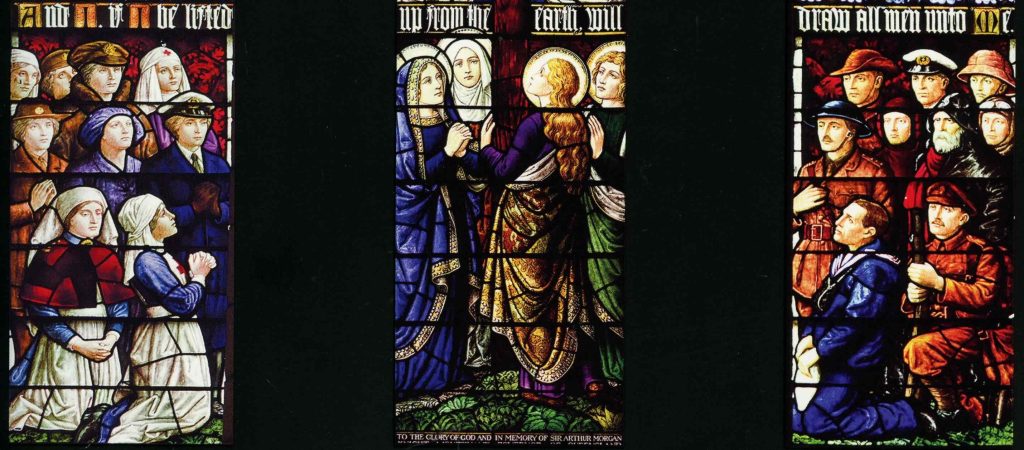

The largest Cathedral memorial is a set of stained-glass windows that commemorate all service people lost in the war. The far-right window features a group of servicemen and the far-left window features a group of servicewomen, including nurses. All are in uniform, kneeling at the foot of Christ’s cross.

The windows are remarkable for their time because they place women on equal footing with men, reflecting the extraordinary contribution that women made to the war effort, especially the nurses who worked round the clock in hospitals, casualty clearing stations (usually near railway lines or waterways for easy evacuation) and near the frontlines caring for the sick and wounded.

“The largest Cathedral memorial is a set of stained-glass windows that commemorate all service people lost in the war. The far-right window features a group of servicemen and the far-left window features a group of servicewomen, including nurses” (Denzil Scrivens)

Collectively our Diocese is the custodian of a huge war memorial legacy with important historic roots. This deepens our responsibility to keep raising awareness of these memorials at a time when the pews are not as full as in previous generations.

In this digital age, one thing I encourage all churches with war memorials to do is to ensure that their memorial is fully recorded on the various national and state historical monument registers.

Related Story

Features

Features

Sister Ella McLean: Queenslander, Anglican and WWI nurse

For example, the principal database for war memorials is Places of Pride, a national register of war memorials initiated by the Australian War Memorial. The register aims to record and display every war memorial in the country. Each memorial has its own entry on the register, complete with photos and a short description.

It is up to each owner of the memorial to ensure that it is registered on the Places of Pride website. This is a straightforward process that initially involves visiting the website and creating a free account. Once an account is created the church can submit a story about their war memorial, along with up to five photos. The Australian War Memorial reviews submissions and if approved (which it usually is), the church’s entry is uploaded onto the website.

A commemorative Anzac stained-glass window at St Barnabas’ Church, Red Hill was dedicated at a special event on 16 December 2018: This panel of the window features Anzac and multi-cultural Defence personnel, inspired by the design of the order of service from the first Anzac Day service held in 1916