Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

Features

“In a time when the Church was very much a male-dominated institution (and eager to remain so) one can only imagine what it meant to women in the earlier half of the 20th century to have a spiritual guide like Evelyn,” says Cathedral parishioner Delroy Oberg on Evelyn Underhill, who is marked in our Lectionary on 15 June

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- The man who would be king

- The saint and the sultan

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

- Hildegard of Bingen

Evelyn Underhill (1875-1941) is commemorated in our liturgical calendar on the day she died, 15 June. Thirty-five years after her death, Michael Ramsay, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, reminded members of the Church of England that this amazing woman was still relevant, and profoundly worthy of her reputation in her own time as a scholar, a teacher, a writer, and a mystic:

“She did much to extend the tradition of ‘spiritual direction’ which elicits people’s own spiritual capacities and helps them find themselves in paths of freedom…She was able to use the insights…from her own studies for the expression of theology and spirituality of a distinctively Anglican kind. Few in modern times have done more to show the theological foundations of the life of prayer and to witness to the inter-penetration of prayer and theology. She has a place of her own, and it is an important one.” (Allchin & Ramsay, 1977, p.22).

Her prolific literary output during her lifetime testifies to all the above. Between 1901 and her death, she wrote or edited 39 books, over 350 articles and book reviews, and hundreds of letters, many of which have been collected into two fascinating anthologies: The Letters of Evelyn Underhill (edited by Charles Williams, 1956), and The Making of a Mystic (edited by Carol Poston, 2010). A large number of the early letters were written to her first spiritual directee, Margaret Robinson. These began as early as 1904, at which stage she was passing from passive resistance to religion to a dangerous dabbling in ritual magic via ‘The Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn’ between 1904 and 1907. For her it provided fellowship – many members were, like Evelyn, disenchanted with the established religions, but still sought spiritual sustenance. Several did return to their churches. Evelyn herself left hoping to join the Roman Catholic Church. Fortunately for Anglicans, she chose to return to the church of her baptism.

It was not until 1921 that Evelyn recommitted herself to the Church of England. Possible reasons, apart from a longing for spiritual fulfilment and stability, are a breakdown she experienced after World War I, and the death of her dearest friend and spiritual confidante, Ethel Ross Barker. And, perhaps the paradox of her religious life was catching up with her. She had never had a spiritual director of her own, yet for years she had dispensed such advice to others. However, her writings had firmly established her as an authority on theology, spirituality, and most matters religious.

Advertisement

Her success had been achieved with multi-generic acclaim. Evelyn wrote three novels: The Grey World (1904); The Lost Word (1907), and The Column of Dust (1909). These books resounded with mystical and magical themes and occurrences, and reflected a search for meaning, for spiritual identity, the opportunity to live life on a higher plane, and even a quest for Eternity, for ‘the Other’, for God.

However, her quest really began with her annual excursions to Italy and France with her mother. Through art and architecture, her soul was gradually growing “into an understanding of things.” In her first letter to her first spiritual directee (Margaret Robinson), she admitted:

“…this state of spiritual unrest can never bring you to a state of vision, of which the essential is peace…and struggling to see does not help one to see. The light comes, when it does come, rather suddenly and strangely….” (Letters, 1956, p.51)

Thus, it is not surprising that she was preparing to tackle her opus magnum, Mysticism (1911); and in what must have been God’s extraordinary planning, Margaret Robinson became Evelyn’s secretary, with her trusty typewriter, and her ability to translate the works of the German mystics.

Icon of Evelyn Underhill by Suzanne Schleck (schleckicons.com)

In May 1911, she wrote to another friend, Mrs Meyrick Heath:

“Is it not amazing when one can stand back from one’s life and look back down it – or still more, peep into other’s lives – and see the action of the Spirit of God: so gentle, ceaseless, inexorable, pressing you bit by bit whether you like it or not towards your home? I feel this more and more as the dominating thing…” (Letters, 1956, pp. 126-7).

Advertisement

What does it matter really that it was another decade before Evelyn finally surrendered to the call of God – to recommit to the Church of England? Then, with her enigmatic, unpredictable and inexplicable capacity for paradox, she asked the revered Roman Catholic scholar and writer, Baron Friedrich von Hügel, to be her spiritual director.

From then on, she went from one triumph to another. In 1921 she became the first woman to deliver the Upton Lectures at Oxford University. In 1927 she was the only female speaker at the Anglo-Catholic Congress, and in the same year she was part of the Commission promoting the 1928 Book of Common Prayer (which was rejected in England, but could be used in the Australian Church). To crown a glorious year, she was made a Fellow of King’s College, London. From 1929 to 1932 she was the religious editor for The Spectator – a prestigious position.

However, her most significant work began in 1924. She conducted her first retreat at Pleshey Retreat House, in Chelmsford Diocese. She was in such demand that she gave retreats at various houses at least three times a year. Some of her most popular books – for example, Light of Christ – were reproductions of her retreat addresses.

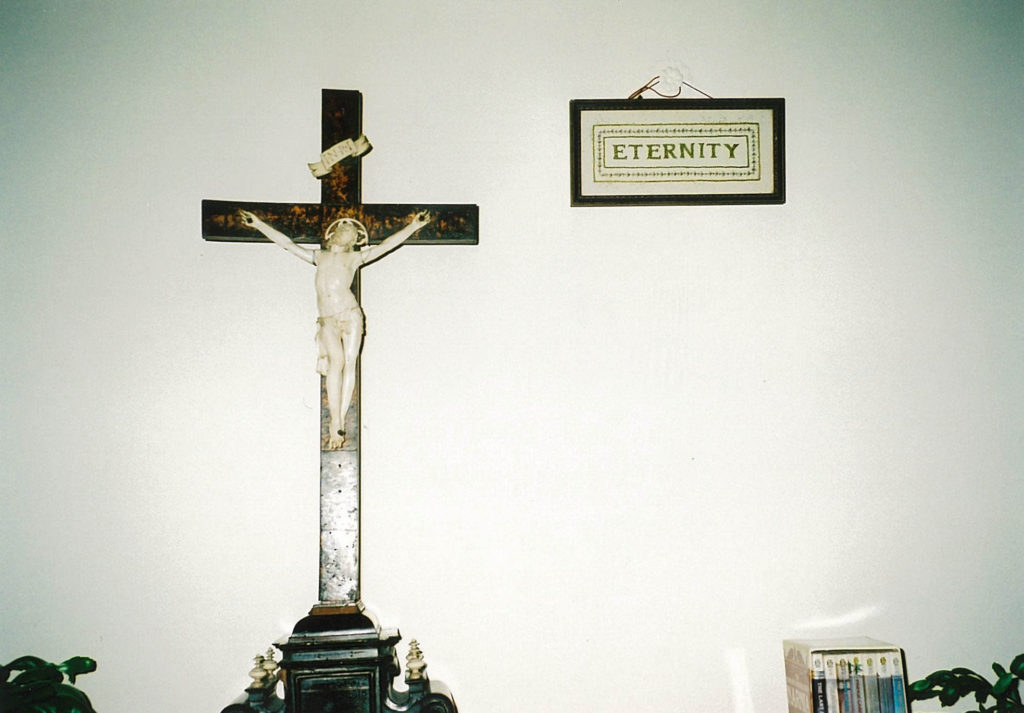

“In the sitting room of the Pleshey Retreat House is the framed ‘Eternity’ embroidery, which Evelyn Underhill created herself, and the crucifix which she brought back from Italy”

In a time when the Church was very much a male-dominated institution (and eager to remain so) one can only imagine what it meant to women in the earlier half of the 20th century to have a spiritual guide like Evelyn. To one of her ‘lambs’, she wrote:

“The Christian life is something so rich, deep, supple and altogether lovely….and not anything which asks more than we can do…So keep calm like a good child, won’t you.” (Letters,1956, p.192)

And to another:

“My poor lamb, I am so terribly sorry for you. I know it is horrible, but it is really all right.” (Ibid, p.224)

Evelyn and her husband Hubert Stuart Moore never had children. They had cats instead – which is why she realised one distressed directee was much in need of “a paw in the dark”. Clearly her methods of direction did not preclude adopting a maternal role. However, her ‘lambs’ did not escape the stern reminder that the spiritual journey would be rough and require discipline. After all, she was speaking from experience!

“…if you choose Christ, you start on a route that goes over Calvary, and that means the apparent loss of God as a bit of it…This means total sacrifice. So face up to it, and thank Him…for the privilege of being allowed to taste a little bit of Christ’s suffering…” (Ibid, p.224)

She was a truly exceptional person. The Cropper biography (The Life of Evelyn Underhill, 1958) assisted in my own return to the Anglican Church. After writing my Master’s thesis on her, I went to England to undertake further research at King’s College, London – her alma mater – where I held in my hands her original journals and letters. As I read her Will, tears rolled down my cheeks. She asked that any surviving cats be humanely put to sleep, if they could not be rehomed. I, too, love cats. I have been to Pleshey twice, and handled a newly discovered batch of her letters which formed the nucleus of the Poston book. I have stood outside her home at 50 Campden Hill Square, where the round blue plaque on her former home signifies that a famous person once lived there; and, I have placed flowers on her grave in the Cemetery of St John’s Parish Church, Hampstead, and wished I had known her.

But, of course, we can know her through her writings; and these spiritual gems will help us to know God better as well.

A.M. Allchin & Michael Ramsay. 1977. Evelyn Underhill: Two Centenary Essays. SLG Press, Oxford, 1977.

Evelyn Underhill’s former home at 40 Campden Hill Square, Kensington, has the blue plaque indicating a famous person once lived there

On one of her visits in 2009, Delroy Oberg placed the crucifix and flowers on Evelyn’s grave in the cemetery attached to St John’s Parish church, Hampstead

Delroy Oberg outside Evelyn Underhill’s home at 40 Campden Hill Square, Kensington in 1989